The Ancient “Time Capsule” buried from one of the most catastrophic volcanic disasters in human history has been excavated on the coast of Turkey, providing new “fascinating” evidence about the Cataclysmic Event – Great Flood.

In a paper published on December 28, 2021, by the National Academy of Sciences, an international team of researchers presented evidence of a devastating tsunami that followed the volcanic eruption of Thera (modern Santorini, Greece), a volcanic island in the Aegean Sea, approximately 3,600 years ago.

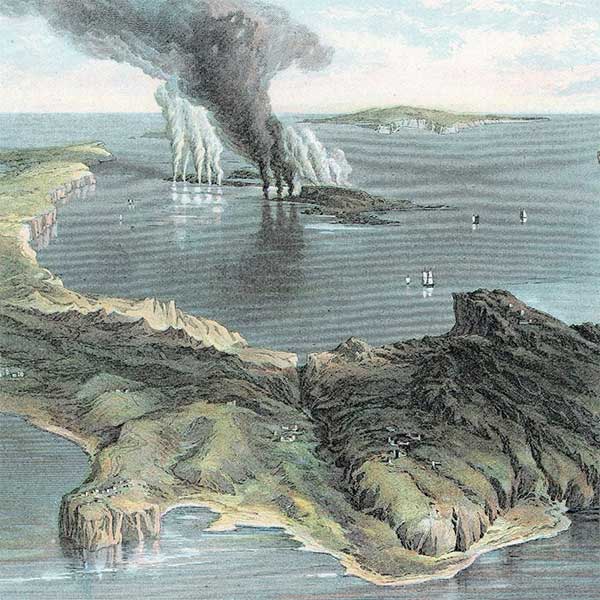

A depiction of the volcanic island of Thera (Santorini, Greece) during the eruption. (Photo National Geographic).

The “super colossal” eruption of Thera, rated a 7 (on a scale of 8) on the volcanic explosivity index, is considered one of the most destructive volcanic eruptions in human history, likened to the explosion of millions of atomic bombs that once leveled Hiroshima.

Many scholars believe that the painful memory of the volcanic disaster that occurred during the Bronze Age (around 1600 BCE) may be reflected in Plato’s allegorical tale of the sunken city of Atlantis, written more than a thousand years later, and the horrific impact of this event is also recorded in the chapter of “10 Plagues” in the Bible.

Although there are no direct records detailing the volcanic eruption or the subsequent tsunami, researchers have now found a way to ascertain their scope and impact on life in the Mediterranean at that time—most notably on Minos, one of Greece’s most magnificent civilizations that collapsed around the same time, in the 15th century BCE.

Beverly Goodman-Tchernov examining a layer of ash at a site from the Bronze Age in Çeşme-Bağlararası, Turkey. (Photo National Geographic).

Unveiling a “Great Disaster” Tsunami

The article states that the research was conducted at the archaeological site of Çesme-Bağlararası, located in the famous resort town of Çesme on Turkey’s Aegean coast, about “a paradise” 100 miles northeast of Santorini. Investigations began in 2002 after ancient pottery was discovered during the construction of an apartment building.

Since 2009, archaeologist Vasıf Şahoğlu from Ankara University in Turkey has been responsible for directing the excavations in this area, which was continuously inhabited from the 3rd millennium to the 13th century BCE.

He discovered collapsed city walls, layers of ash, and fragments of pottery, bones, and shells. Şahoğlu quickly reached out to colleagues in various fields, including Beverly Goodman-Tchernov, a marine geology professor at the University of Haifa in Israel and a National Geographic explorer specializing in identifying tsunamis in archaeology and geology.

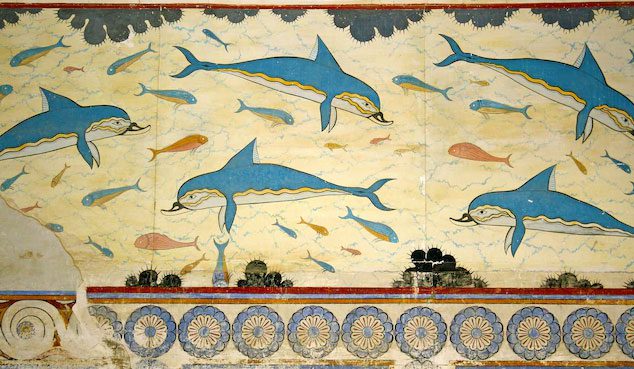

A mural from the Minoan palace at Knossos, Crete, showing how the Thera disaster disrupted trade routes and infrastructure of the Minoan people. (Photo National Geographic).

“The tsunami was primarily erosive… and not capable of depositing material, so we were very excited to find these artifacts,” said Floyd McCoy, a geology and oceanography professor at Windward Community College in Hawaii, in an email.

McCoy has studied the volcanic eruption and tsunami events at Thera but did not participate in the recent project, calling the research a “truly significant contribution not only extremely useful for the science of tsunami sedimentology but also greatly meaningful in understanding the Thera lava eruption.”

A Disaster with No Casualties?

One of the biggest mysteries of the Thera volcanic eruption is the surprisingly low number of casualties recorded: over 35,000 people are estimated to have died in the tsunami caused by the Krakatoa eruption. However, to date, only one body has been identified as “potentially” a victim of the natural disaster: a man found buried under rubble on the Santorini archipelago during investigations in the late 19th century.

Various hypotheses have been proposed: smaller eruptions occurring earlier may have caused people to flee the area before the historic dual disaster; victims may have been incinerated by the searing heat of the lava; drowned at sea; or buried in unmarked mass graves.

Map showing the location of Thera – now Santorini. (Photo National Geographic).

“How could one of the worst natural disasters in history leave no human casualties?” Şahoğlu wondered.

Professor Goodman-Tchernov suggests that researchers may have failed to recognize deposits from past tsunamis, and they may indeed have discovered victims of the Thera disaster but “overlooked” or “failed to connect” the clues together.

However, in Çesme-Bağlararası, researchers report that they have found the first victim of this cataclysmic event: the remains of a young, healthy man with signs of trauma from impact forces, found lying in the debris of the tsunami. The skeleton of a dog was also discovered nearby at the same time.

The examination and dating analysis of the two recently discovered skeletons will begin next month.

Artifacts remaining from one of the most horrific disasters in human history. (Photo National Geographic).

The “Raging” Waves

Researchers have identified that four tsunami waves struck Çesme-Bağlararası over the course of days to weeks. This “particularly intriguing” to McCoy, as he previously indicated that there were four phases leading up to the Thera volcanic eruption. Researchers have long questioned: “Which phase of the eruption triggered such a catastrophic tsunami?“

As the water receded between tsunami waves, it appears that surviving residents took the opportunity to search for victims amidst the chaos. A depression was found just above the body of the young man—a sign that he was “clutching” or “grasping” something due to a strong pull. However, the person stopped too soon to save the victim.

Evidence of the efforts to search for victims during this tsunami indicates concern for the burial of the unfortunate victims after the disaster, possibly in mass graves to mitigate the outbreak of disease afterwards, helping to explain the general absence of human remains from the levels of destruction in the Aegean.

The Quest for Truth Continues

According to historical records, the Thera volcanic eruption is dated to a time known as Late Minoan IA, associated with Egypt’s 18th dynasty in the 1500s BCE. However, radiocarbon dating on wood fragments found in the ash layer at Akrotiri dates back to the late 1600s BCE—over a century apart.

While scientists continue to debate the timing of the Thera disaster and the damage it inflicted on the Mediterranean during the Bronze Age, researchers hope that this discovery will encourage archaeologists involved in the project to re-examine whether they missed any “elusive” evidence regarding one of the most devastating natural disasters in human history.

Meanwhile, Şahoğlu hopes that this archaeological site—located in the heart of a famous resort town—will someday become a tourist attraction.

Jessica Pilarczyk, an assistant professor of earth sciences and head of research on natural hazards at Simon Fraser University, stated that humanity must face not only hazards that still lurk offshore from the past but also threats that may arise in the future. She added that this research is a hope that can raise public awareness and even preparedness regarding natural dangers.

“Just because disasters like tsunamis occur too infrequently and far apart, sometimes centuries apart before another catastrophic event happens, does not mean that people can consider themselves safe.”