Surrounding the discovery of the “Largest Burial Cave in Vietnam” or “Ma Cave“, which houses hundreds of wooden coffins from ancient times that are “hung” and “buried” in mountain caves along the banks of the Ma River and Luong River in Hoi Xuan commune, Quan Hoa district, Thanh Hoa province, a series of questions have arisen: What is the connection between the burial customs in Quan Hoa and those of the inhabitants of some neighboring countries?

Burial Customs Around the World

The practice of burying the dead in mountain caves is quite common globally, primarily in mountainous regions of Asia (especially in Turkey and China) and the Americas (where Indigenous peoples have ancestors who migrated from Asia over 10,000 years ago).

The origins of this practice are linked to the symbolic nature of caves – the first home of humanity. Consequently, caves are equated with a woman’s womb, the place where humans are born, and to be reborn, the deceased must return there. Mountain caves are also seen as a connection between earth and heaven, the closest place to the sky, making it the best location for burying the dead (ancient Chinese emperors were often buried in caves so that their souls could easily ascend to heaven and become ancestors or deities).

Caves used for burial can be natural or artificial (Egyptian pharaohs were buried in pyramid-shaped structures resembling mountains). A variant of this burial custom involves placing the dead in stone coffins within stone graves (still seen among the Hmong) and burial sites featuring stone pillars (noted in areas inhabited by the Muong people)…

“Ma Cave” in China

In China, “ma cave” is no longer a shocking phenomenon, as it has been discovered in 13 provinces and autonomous regions, from Sichuan province in the west to Fujian in the east, and from Shaanxi in the north to Guangdong in the south. In the city of Shangluo in Shaanxi province, archaeologists have uncovered 680 sites with 4,220 burial caves (natural or artificial) where wooden coffins are placed inside or hung on steep rock faces. Most of the individual burial caves are rectangular, about 3 meters deep. In collective burial caves, the walls are engraved with images of kitchens, wells, and altars.

The most famous burial site in China is located on Longhu Mountain in Jiangxi province, known as “Heavenly Palace” for its breathtaking scenery, and it is also the birthplace of Daoism. Here, along the rock walls by the river, from 20 to 300 meters above the water and facing east, there are hundreds of caves or burial pits, inside of which hang one or more wooden coffins shaped like houses or boats, weighing from 150 to 500 kg.

Artifacts found in these coffins indicate that the owners of these burial caves were the Baiyue people who lived during the Spring and Autumn – Warring States period (770 to 221 BC). Due to the large number of burial caves distributed over a rugged and unique terrain, this mountain has been honored as the “Number 1 Natural Archaeological Museum” in China. In 1983, it was placed under special protection by the Chinese government, and in 2000, it was designated as one of China’s 11 national geological conservation areas.

Over 10,000 people, including scholars and local residents, have proposed various interpretations. Some believe that over 2,000 years ago, the water level of the river was higher than today, allowing ancient people to transport coffins by boat to caves not far from the riverbank. Others suggest that the burial caves were originally in lower mountainous areas but were elevated due to geological changes.

Others propose: that the ancients created burial caves on high cliffs to protect their ancestors’ graves from desecration, and to achieve this, they built scaffolding from bamboo or wood or used pulleys to hoist heavy coffins from boats. Some even hypothesized that ancient people used primitive forms of hot air balloons or cranes to move the coffins up the cliffs. Certain research groups have conducted experiments to replicate traditional methods of lifting people and heavy objects to heights. However, no explanation has been universally accepted.

“Ma Cave” in Indonesia

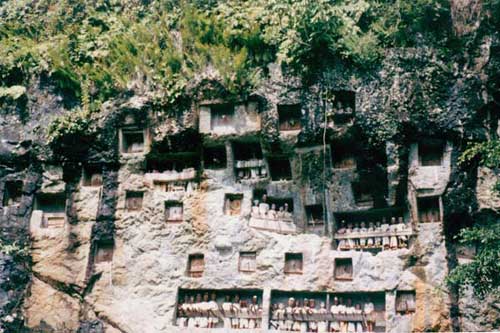

In Indonesia, burial customs have been preserved among some Toraja groups on Sulawesi Island. Interestingly, some scholars believe their ancient ancestors migrated from Dong Son, Vietnam, or from Indochina. With a relatively stable and isolated geographical-historical context, the traditional Toraja culture has managed to retain many Dong Son customs until recently, such as tattooing, teeth blackening, chewing betel, playing gongs, or using mortars as signals when someone dies.

Toraja grave statues overlooking and protecting the fields,

villages of the living. (Photo: tabisite.com)

Notably, the traditional Toraja house (tongkonan) resembles the shape of the roofed house depicted on the Dong Son bronze drum from the Dong Son culture. Researchers have also found that the Toraja pestle for pounding tree bark is identical to the pestle of the Phung Nguyen culture, as well as a near-perfect similarity in patterns between a Toraja bamboo tube and a bamboo tube from the Central Highlands.

To this day, in some places, the Toraja people still preserve the burial custom of placing coffins (usually of dignitaries or wealthy individuals) in artificial caves on cliff faces. These coffins are shaped like buffaloes (the mythical animal that rules the underworld) or boats (similar to the homes of the living). Interestingly, they refer to these burial caves as liang (cave) or lo’ko (hole), terms that are clearly very similar to the Vietnamese words for cave and hole.

Human skulls in the “Ma Cave” of Indonesia (Photo: tabisite.com)

For the Toraja, the burial custom is associated with the belief that the resting place of the dead is to the west or south, “the place closest to heaven,” “the place with the door to heaven,” “the place with a ladder connecting earth to heaven,” “the headwaters of a river” linked to their ancestor legend that “they sailed to a new land.” Therefore, the ideal burial site is in mountain caves. The act of taking the dead to these places is believed to help their souls transcend, find peace, protect the living, and be easily reborn in a new life.

Today, Toraja funerals and burial caves have become two “tourism products” of Indonesia.

The Connection Between Burial Customs in Quan Hoa and the Plain of Jars in Laos

|

| One of the stone jars at the Plain of Jars. (Photo: CAND) |

In Laos, the Plain of Jars, with over 3,000 large stone jars (height: 2 – 3 m, diameter: 1-3 m, weight: 2-13 tons), is the most famous archaeological site and also one of the most mysterious. In the future, it is likely to be recognized as a world heritage site.

To date, many intriguing legends and scientific hypotheses surround three main issues: the owners, the dating, and the function of these stone jars.

According to the scientific hypothesis most supported by scholars, the Plain of Jars is a large burial site where the stone jars served as coffins or containers for the ashes of the deceased who were cremated in a nearby cave. Most of the grave goods found in the cave and jars date from the 5th century BC to the 8th century AD. Some of the earthenware artifacts bear a close resemblance to Dong Son bronze drums, indicating a cultural connection between the Plain of Jars and Dong Son culture.

Meanwhile, in Thailand, archaeologists have discovered a significant burial site in Ongbah Cave with over 90 wooden coffins shaped like boats dating from 403 BC to 25 AD. Fortunately, among the artifacts that escaped local looting, six bronze drums remain. Notably, the skeletons in the coffins indicate that their owners were taller than the indigenous Southeast Asian populations. This has led some scholars to link the owners of the coffins in Ongbah Cave with those of the Plain of Jars, and subsequently, with the legends and scientific hypotheses about the migration of Indo-European peoples from Central Asia through India to Southwest China and Indochina.

Currently, perhaps the greatest mystery of the burial sites in Quan Hoa lies in the unusually sized skeletons found there. It is hoped that future DNA analyses will unravel these mysteries and reveal the connections between the owners of the burial sites in Quan Hoa, the Plain of Jars, and other distant regions.