Scientists have accurately identified the locations of significant “super-emission” methane leaks from oil and gas production, contributing up to 12% of methane emissions to the atmosphere annually. Identifying and repairing these sites could save billions of dollars for many countries.

Analysis of satellite images from 2019 and 2020 reveals that the majority of the 1,800 largest methane sources in the study originate from six major oil and gas-producing countries: Turkmenistan leads, followed by Russia, the United States, Iran, Kazakhstan, and Algeria.

The research team led by climate scientist Thomas Lauvaux from Paris-Saclay University, along with colleagues, believes that sealing these leaks would not only benefit the planet but could also save those nations billions of U.S. dollars.

The gas bursts in which oil and gas producers intentionally release methane are a significant source of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere.

Super-emission devices are sources that emit at least 25 tons of methane per hour into the atmosphere. These large, sporadic bursts account for only a small fraction of the methane released from oil and gas production entering the Earth’s atmosphere annually.

Euan Nisbet, a geochemist at Royal Holloway, University of London in Egham, who was not involved in the study, stated that cleaning up such leaks would be an important first step in reducing overall emissions. “If you see someone seriously injured in a road accident, you tend to the wounds that are bleeding the most,” he remarked.

Methane has a warming potential in the atmosphere that is approximately 80 times greater than that of carbon dioxide, although it tends to have a much shorter atmospheric lifespan—ranging from 10 to 20 years or longer, compared to hundreds of years for carbon dioxide. Greenhouse gases can enter the atmosphere from both natural and anthropogenic sources.

In oil and gas production, major methane explosions can result from accidents or leaking pipelines or other facilities, according to Lauvaux. However, many of these leaks often result from routine maintenance activities, the research team found. For example, instead of shutting down for several days to clear gas from the pipelines, managers might quickly open valves at both ends of the line, releasing and burning gas swiftly. This practice is notably visible in satellite images, referred to as “two giant plumes” along a pipeline, Lauvaux explained.

Preventing such practices and repairing leaking facilities is relatively straightforward, which is why such changes could yield low-hanging fruit in addressing greenhouse gas emissions. However, identifying specific sources of these massive methane emissions poses a challenge. Aerial studies can help pinpoint some major sources, such as landfills, dairy farms, and oil and gas producers, but such flights are limited by both area and time constraints.

Satellites, such as the TROPOspheric Monitoring Instrument from the European Space Agency and TROPOMI, provide a much larger window in both space and time. Scientists have previously used TROPOMI to estimate the overall leakage from oil and gas production in the giant Permian Basin in the southwestern United States, discovering that the region emits methane into the atmosphere at twice the previously thought rate (SN: 4/22/20).

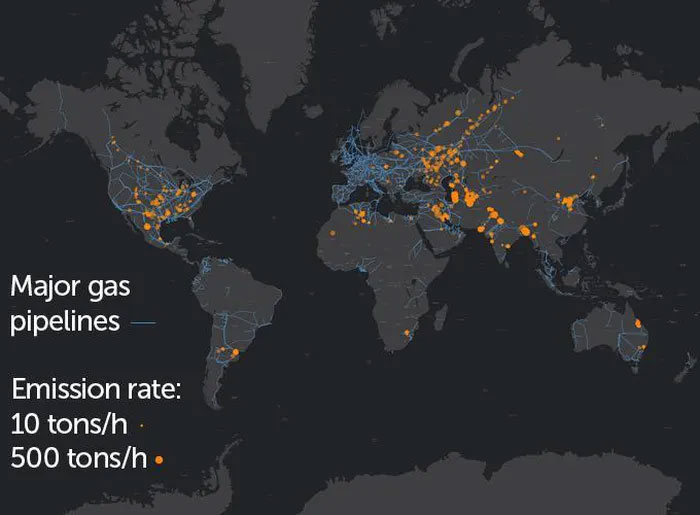

Hotspots

Satellite images have helped scientists identify super-emission sources of methane from oil and gas (orange circles), with the largest emissions reaching up to 500 tons of gas per hour into the atmosphere (larger orange circle). The blue line indicates gas pipelines. Several emission hotspots trace these pipelines, such as in Russia.

Locations of super-emission methane discovered in 2019–2020.

In the new study, the research team did not include sources from the Permian Basin among the super-emission sources; the large emissions from that area result from many closely grouped but smaller emission sources. Because TROPOMI cannot see through clouds, other global areas, such as Canada and the equatorial tropics, were also not included.

However, that does not mean those areas are inactive, Lauvaux noted. “It’s just that there is no available data.” Based on this overarching perspective from TROPOMI, Lauvaux and other scientists are currently working to fill those data gaps by utilizing other satellites with better resolution and cloud-penetrating capabilities.

Researchers indicate that preventing all these large leaks, which account for about 8 to 12% of total annual methane emissions from oil and gas production, could save these countries billions of dollars. Moreover, reducing those emissions would benefit the planet similarly to eliminating all emissions from Australia since 2005 or removing 20 million vehicles from the roads in a year.

Daniel Jacob, an atmospheric chemist at Harvard University who was not involved in the study, mentioned that such a global map could also be useful for countries to achieve their goals under the Global Methane Commitment announced in November at the annual United Nations climate summit.

Signatories of the commitment have agreed to reduce global methane emissions by at least 30% compared to 2020 levels by 2030. These new findings, Jacob stated, could help achieve that goal as it “encourages action rather than despair.”