In the impenetrable darkness of Sapphire, an unincorporated community in North Carolina, USA, a man in camouflage slowly raised his rifle to his shoulder: Jason Bullard aimed with one eye closed, fixing his determined gaze on the target.

The silence of the town was abruptly shattered by the sound of a pellet gun, leaving a small crack in the stillness. “That seemed like one,” Bullard muttered as the shot rang out. But as he approached to check, it turned out to be just a fuse box.

But Bullard’s real target was the armored armadillos, encased in hard shells that made them blend into the darkness like rocks, revealing only their glowing eyes in the night.

Jason Bullard had to learn how to exterminate armadillos with a pellet rifle, as .22 caliber bullets could not kill them.

Like Alien Hunting

In the past year, the town of Sapphire has been invaded by an army of armadillos from the tropical regions of Texas. Only a wave of drought caused by climate change could explain the presence of these creatures here.

They marched over 1,000 kilometers just to reach the town’s lawns, digging holes and tearing up gardens, prompting homeowners to pick up the phone and call Bullard early in the morning.

Initially, he took on this job as a bounty hunter. Homeowners in Sapphire were willing to pay Bullard $100 for each armadillo he shot. But as they realized the sheer number of invaders, the residents of this town hired Bullard full-time with a fixed salary.

They assigned him a perimeter to patrol around private properties and a golf course, where Bullard was tasked with patrolling each night, aiming and shooting at anything he suspected might be an armadillo. In just two weeks of November, Bullard managed to take down eight, half the number he had shot in the entire previous year.

“This work feels like hunting aliens,” Bullard said. “When these armadillos arrive, we know nothing about them. They appear suddenly and in overwhelming numbers. These creatures are not easy to shoot.”

The first time he encountered an armadillo in Sapphire was in 2019. Bullard shot it with a standard .22 caliber rifle. But the armored creature did not die. It mysteriously vanished into the night with a kangaroo-like leap, leaving the hunter gaping in disbelief.

“I really couldn’t believe it,” Bullard said. So for the entire following year, he had to stake out every night on a local golf course, moving from hole to hole just to figure out how to take down these armadillos.

The battle resembled a match-up between Tiger Woods and Davy Crockett, except it took place at night, with one side being the hunter and the other side the armadillos glowing with a dull gray light, the energy stored from sunlight during the day.

The armadillo is known for its powerful jumps within a range of 1 meter. It allows the creature to escape even from bear pounces.

The Armadillo Invasion of America

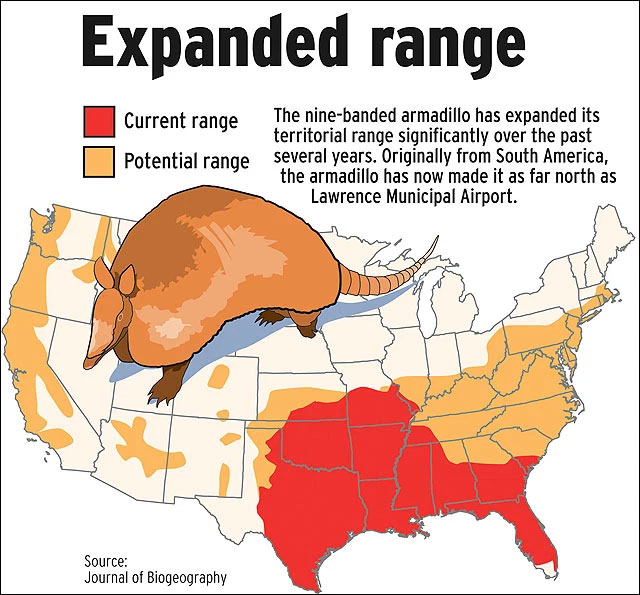

The appearance of creatures like armadillos in North Carolina is indeed a curious event. Native to Mexico, these mammals have only followed human migration into the U.S. since the late 19th century.

Armadillos are divided into about 20 species, the most famous being the nine-banded armadillo and the three-banded armadillo – identifiable by the rings of armor around their bellies. This creature is notable for its extremely tough outer armor.

It is not an armor developed from keratinized skin like that of the pangolin, but rather its bones. The bony armor allows armadillos to defend against potential predators and sometimes enables them to curl up and roll like a steel ball when threatened.

After entering the U.S., armadillos quickly exploded in population, with females capable of giving birth to up to four young per litter and having multiple litters in their lifetime. Nonetheless, their adaptation to hot, dry climates means armadillos could only thrive within the boundaries of Texas.

There, they are famous for being marathon runners in the desert. During the Great Depression, Texans often had difficulty catching armadillos for food because they can jump very high and run quickly over distances greater than 10 meters.

Their meat is commonly consumed in Central America, and in the Southern U.S., armadillo was once dubbed “the poor man’s pork.” However, it had never surpassed state borders like Texas to reach Sapphire, nearly 1,300 kilometers away.

This peaceful town is situated on a beautiful plateau nestled deep within the towering Blue Ridge Mountains. Unlike Texas, the climate here is more temperate mixed with tropical, with ample rainfall nurturing the lush fir forests on a mossy forest floor.

In winter, Sapphire even experiences snowfall, while armadillos in Texas are not born to see snow. This is why when the first woman here claimed she had seen an armadillo, people thought she was either hallucinating or just drunk.

Armadillos have armor surrounding their bodies, and they can roll up to roll like a ball.

But the truth is that these creatures have been marching northward and invaded the Sapphire Valley last year. Even the rivers in Missouri, Iowa, and Nebraska could not deter them.

Biologists say that armadillos can hold their breath for up to six minutes, allowing them to walk along the bottom of rivers or even inflate their intestines to float across to the other side like a deflated balloon.

“It’s only a matter of time before we see the range of armadillos expand into other states,” said Colleen Olfenbuttel, a biologist at the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission.

They Will Soon Parade Outside the White House Lawn

In March 2019, just as armadillos began to reach North Carolina, officials in Virginia also received a perplexing call from a resident in Buchanan County. The woman was bewildered to discover cone-shaped holes in her garden. She had captured the first photograph of an armadillo in the state.

“It was completely shocking,” said Nancy Moncrief, curator of mammal genealogy at the Virginia Museum of Natural History. “My colleague said it might have come from eastern Kentucky, but I had to ask, ‘What in the world are they doing in Kentucky?’

Just a month later, Moncrief collected the first specimen, an armadillo killed by a hunting dog. The carcass was immediately brought to her museum, and its bones preserved as an official specimen marking the presence of this animal in Virginia.

“We posted it on Facebook, and everyone was amazed, saying, ‘Oh my God.’ Moncrief said. She suspects that these animals are following river valleys, where they can find abundant food along the Appalachians and will soon spread throughout Virginia.

Eventually, armadillos may soon march to the White House, reaching New York and beyond. “They will continue to creep northward,” Moncrief said.

The first armadillo carcass found in Virginia on display at the Virginia Museum of Natural History in Martinsville.

As stated, nothing could explain the wave of armadillo migration across America except for an ongoing climate crisis. For a species not suited for winter like the armadillo, global warming inadvertently makes temperate areas more hospitable to them.

The paradise for tropical species is beginning to explode. Around the town of Sapphire, armadillos can now happily root in the soil with their snouts and claws, feasting on insects year-round at elevations above 1,200 meters. “Here, we no longer experience truly frigid winters, and I’m sure that has helped this creature,” Olfenbuttel said.

Lynn Robbins, a veteran biologist at Missouri State University, is one of the first to study armadillos in his state. He said, “As the Earth warms, it’s helping them. As long as there’s water and soil to dig, armadillos will likely move right in. But people are still amazed to see them.”

Dealing with the damage caused by armadillos is a challenge. “They’re very hard to trap, and I don’t know if there’s any repellent that can deter them,” Olfenbuttel said.

Robbins agrees; he struggled to catch his first armadillo for research. Mainly because this creature can perform a powerful jump within a meter range, a skill it developed to escape bear pounces. Armadillos have poor eyesight, but their hearing is extremely sensitive.

“If it’s really quiet, you can get close and grab their tails. But be cautious because they are very strong. It’s best to have a bag ready to catch them before they jump,” Robbins said.

Jason Bullard uses hunting dogs and thermal imaging to detect armadillos.

In Sapphire, Bullard often sets box traps to catch armadillos right at the entrances of their burrows. He dislikes leg-hold traps because they can hurt the animal. If he must kill an armadillo, Bullard opts for the least painful method possible.

“I have no malice, and neither do they. They haven’t done anything wrong; they’re just trying to eat and survive. But because they are causing damage, we have to remove them,” he said. The lawns in Sapphire, including the golf courses, are being torn apart by armadillos. They dig holes everywhere, and just one patch looks like it has had dozens of tent pegs pulled up.

Besides armadillos, locals also hire Bullard to deal with wild pigs, beavers, skunks, and even otters – which eat the fish stocked in recreational ponds. These wild animals are allowed to coexist with us until they cross a certain line. In the case of armadillos, they are ruining beautiful lawns and enjoyable golf games for humans.

The traces left by an armadillo on the residential lawn in Sapphire.

“I have to do the job to satisfy those who hired me,” Bullard said. And so every night, he takes up his pellet gun and patrols the town. Accompanied by his dog and a thermal imaging device, Bullard has now become a sharp-shooting armadillo hunter.

But the creatures are still making their way north, breeding at an uncontrollable rate. The battle between humans and these animals has only just begun in the northern states of America.

“I’m very curious to see where these creatures might appear next,” Olfenbuttel said. With the pace of ongoing climate change, it may not be long before we see tropical animals like armadillos, originally from Mexico, make their way to the lawns outside the Oval Office of the White House and dominate the surrounding temperate lands.