The Amniotic Fluid Embolism syndrome is a very rare occurrence in obstetrics. Despite its rarity, 80% of cases result in death. Dr. Nguyen Cong Nghia, currently a PhD candidate in Reproductive Epidemiology at the University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill, USA, has written a special article for VietNamNet on this syndrome.

This syndrome was first described by Meyer in 1926; however, its clinical symptoms did not attract the attention of obstetricians until 1941.

A thorough retrospective review of these cases was first conducted by Morgan in 1979. Since then, a national registry system for this condition has been established in the United States.

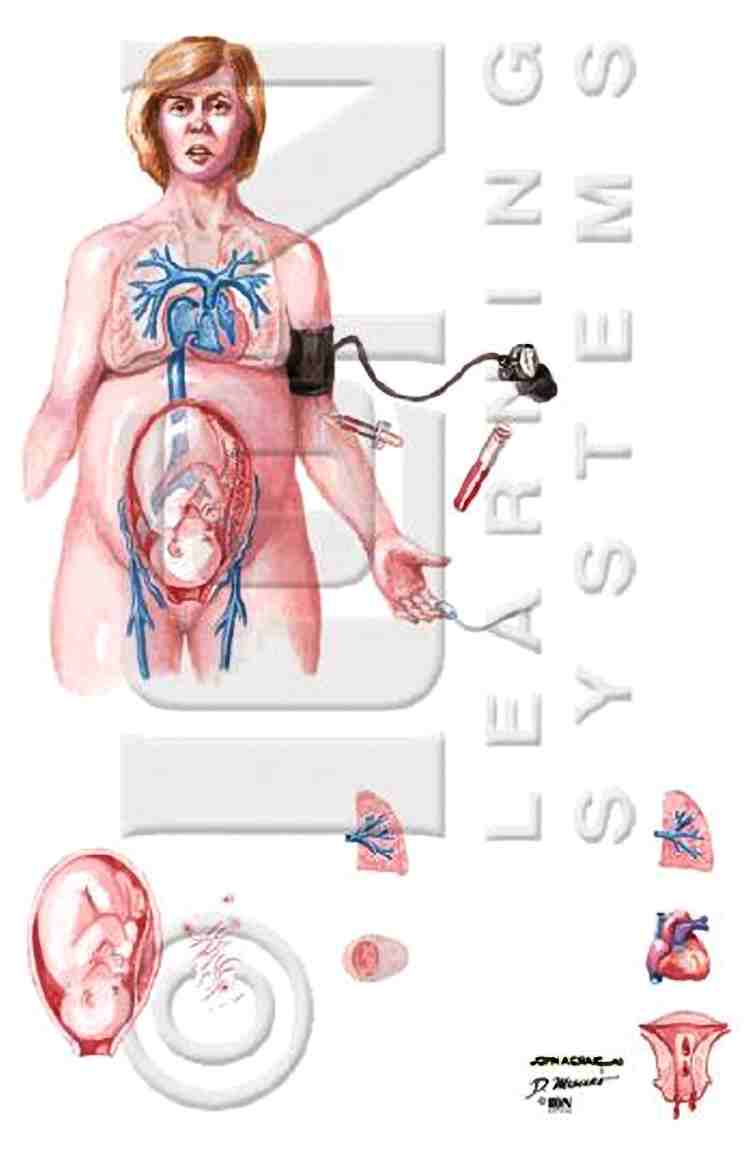

The Amniotic Fluid Embolism syndrome occurs when amniotic fluid, fetal cells, air bubbles,

foreign substances, hair, or other fragments of fetal tissue enter the mother’s bloodstream,

leading to acute respiratory and circulatory failure. (Image: netterimages, VNN)

Rare, Difficult to Diagnose, but Dangerous

This condition occurs with a very low frequency, approximately 1 case in 8,000 – 30,000 pregnancies. In the entire UK, there are only 3-4 cases each year. However, the mortality rate is extremely high, around 80% of affected cases.

Due to the low number of cases, there is currently no clear evidence of what constitutes risk factors. Nevertheless, it has been suggested that older mothers, those with multiple births, unusually rapid labor, larger fetuses, or the use of uterotonics may be associated with an increased risk of this condition.

Generally, amniotic fluid embolism typically occurs during labor, elective cesarean delivery, but can also happen during abortion, amniotic fluid infusion into the uterine cavity, abdominal trauma, or even after delivery.

Experts consider this syndrome to be essentially a process of “anaphylactic shock,” rather than merely a “vascular obstruction.” The reason being, it is suspected that the entry of amniotic fluid and fetal cells into the circulation stimulates the mother’s anaphylactic response to antigens from the fetus.

However, there is a common misconception that the presence of fetal cells such as epithelial cells or trophoblasts in the mother’s blood circulation (from the pulmonary artery) is a definitive sign for diagnosis. Data shows that these cells are often found in the blood circulation of mothers who do not have this condition.

The presence of these cells is a suspicion in suspected cases, but must be combined with the clinical picture of hemodynamic and respiratory disturbances to confirm the diagnosis.

Currently, experts are focusing on the breakdown of giant cells to release histamines and tryptase enzymes, activating another complex cascade of responses.

Intensive Resuscitation for Emergency…

|

| Examination of the mother before childbirth. (Image: VNN) |

While waiting for further research results from experts, we should monitor the progression of this syndrome…

The pathological process typically occurs in 2 stages.

Stage 1 involves constriction of the pulmonary arteries, acute pulmonary hypertension, and right ventricular failure leading to hypoxemia. Hypoxemia causes destruction of cardiac and pulmonary capillaries, resulting in left heart failure and acute respiratory syndrome.

About 50% of cases that survive Stage 1 (lasting about 1 hour) will enter Stage 2, which involves synchronous bleeding and disseminated intravascular coagulation.

The clinical picture appears rapidly with signs of acute shortness of breath, sometimes cough, rapid and sudden drops in blood pressure, especially diastolic pressure, cyanosis around the lips and extremities, potential cardiac arrest, or signs of acute pulmonary edema. In obstetric monitoring, fetal heart rate deceleration and uterine bleeding can occur in the late stages.

Differential diagnosis is necessary with many other syndromes such as thromboembolic obstruction, gas embolism, septic shock, acute myocardial infarction, anaphylactic shock from other causes, placental abruption, or local anesthetic reactions.

Treatment is supportive rather than addressing the underlying cause.

For this syndrome, the role of resuscitation staff and techniques is more crucial than that of obstetricians. In case management, resuscitation specialists often apply four main principles in treatment including enhancing ventilation, increasing oxygenation, supporting circulation, and correcting coagulopathy.

From an obstetric perspective, many authors recommend immediate cesarean delivery when possible, first to save the fetus, and secondly to facilitate hemodynamic stabilization. During cesarean delivery, uterine arteries may be clamped on both sides to control bleeding.

The treatment outcomes are low despite all the aforementioned efforts. However, intensive treatment can still provide hope for patient survival. For instance, doctors at KK Women and Children Hospital reported two cases of patients surviving after intensive treatment in 2002. Detailed descriptions of their treatment can be found at http://www.ispub.com/ostia/index.php?xmlFilePath=journals/ijgo/vol1n2/amniotic.xml.

Current research on this condition allows us to conclude that amniotic fluid embolism is a dangerous obstetric complication, with a high mortality rate, unpredictable and unpreventable.

Nevertheless, obstetricians must remain vigilant and provide aggressive treatment when it occurs to increase the chances of survival for both the mother and the fetus.

Dr. Nguyen Cong Nghia (PhD candidate in Reproductive Epidemiology at the University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill)