In just six months, Pfizer transformed an initial failure in testing into a groundbreaking vaccine production campaign, described by U.S. President Joe Biden as a “scientific miracle.”

In the suburbs of Kalamazoo, Michigan, Pfizer operates a vaccine manufacturing facility. This site was chosen to produce the first batch of vaccines using mRNA technology to combat Covid-19.

Few know that before achieving this breakthrough in Covid-19 vaccine production, Pfizer’s first attempt at large-scale vaccine development failed miserably in mid-2020.

However, within just over six months, Pfizer and its partner BioNTech achieved results that President Biden later described as a “miracle” in vaccine development and production, paving the way to end the Covid-19 pandemic.

Starting from Scratch

Before the pandemic erupted, Pfizer and several other pharmaceutical companies such as BioNTech and Moderna were researching the potential applications of mRNA technology for vaccines against diseases like influenza, HIV, tuberculosis, rabies, malaria, Zika, and even cancer treatments.

On March 20, 2020, Mr. McEvoy, the operations director of the Kalamazoo plant, received a letter from Chaz Calitri, the vice president of Pfizer responsible for operations in the U.S. and Europe.

Three days earlier, Pfizer had announced its partnership with the German biotech company BioNTech to develop and produce a trial coronavirus vaccine.

At that time, BioNTech had discovered a way to utilize mRNA vaccines against the coronavirus. However, the German company needed a partner with substantial manufacturing capabilities, technical expertise, and the ability to distribute vaccines on a global scale.

A Covid-19 vaccination center in the U.S. (Photo: Reuters).

Calitri was among the Pfizer executives who selected the Kalamazoo plant as the site for the formulation, production, packaging, and distribution of the vaccine. Kalamazoo is one of the largest steroid manufacturing facilities in the world.

As he embarked on this task, Mr. McEvoy confronted the reality that every critical step in vaccine production would have to be built from scratch. At that time, the machinery needed to combine lipid nanoparticles with mRNA, as well as to filter the final product, did not exist.

In July 2020, Pfizer secured its first agreement to sell 100 million doses of the Covid-19 vaccine to the U.S. government for $1.95 billion.

That month, Mr. McEvoy and several other Pfizer leaders took officials from the Trump administration, responsible for the Covid-19 vaccine development program Operation Warp Speed (OWS), on a tour of the manufacturing facility in Kalamazoo.

However, at that time, all McEvoy could show U.S. government officials was an empty space, accompanied by Pfizer’s resolute commitment to the vaccine’s success.

“This is where hundreds of freezer units will store the final products at -70 degrees Celsius. This is where the vaccine will be packaged. Production rooms will be built in advance, transported by truck from Texas, fully equipped with machinery and piping,” McEvoy told OWS officials.

Moncef Slaoui, an OWS official, expressed his impression of Pfizer’s commitment. The company was utilizing all available resources, manpower, and financial strength to produce the mRNA vaccine, Slaoui stated.

Pfizer procured every special freezer unit it could find from supplier Thermo Fisher and requested that Thermo Fisher manufacture more.

Due to strict cold storage requirements, workers had only 46 hours to fill vials with vaccine, each containing six doses, and store them in freezers before the vaccine became inactive.

Initial mistakes were inevitable. One costly error occurred when Pfizer ordered special freezers from Europe that turned out to be unusable. This batch of equipment still remains unused in storage.

The First Trial Failure

Pfizer’s goal was to create an mRNA vaccine capable of preventing coronavirus infections.

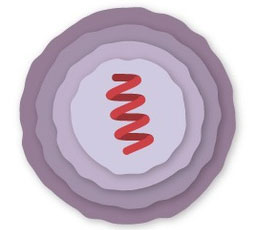

The vaccine molecules contain lipid nanoparticles, which are tiny fat globules that encapsulate an mRNA strand, enabling human body cells to produce proteins that trigger antibody responses, thereby bolstering the immune system against future viral invasions.

However, lipid nanoparticles represented a technology that had never been applied at an industrial scale previously. Without these tiny fat globules, Pfizer could not produce the vaccine.

The vaccine production process was initiated by Pfizer in mid-2020. At this point, Pfizer and BioNTech had figured out how to transition the vaccine formulation process from the laboratory to large-scale industrial production.

Pfizer’s vaccine molecule consists of a lipid shell encasing an mRNA. (Photo: New York Times).

Initially, Pfizer’s experts believed there wasn’t enough time to design, fabricate, and test an industrial-scale device to incorporate mRNA into lipid nanoparticles.

Therefore, they purchased several small-sized jet mixing devices and arranged them in a series of eight parallel production systems. The equipment at that time was small enough to fit on a table.

BioNTech provided Pfizer with the formulation for production at the experimental scale.

“They gave us a blueprint of what they had on hand. That would never be enough to provide vaccines for the entire world. At that time, we had no expertise in this equipment, so we had to figure out how to produce the vaccine at a commercial scale,” said Jinne Adisoejoso, a Pfizer pharmaceutical manufacturing expert.

By September 11, 2020, abnormal signs began to appear in the vaccine production process, Pfizer leaders later reported.

When inspecting the product at the end of the production process, Pfizer experts discovered that the most critical component of the vaccine—the lipid molecule encapsulating the mRNA—had disappeared.

“Our first technical trial failed completely.” Pat McEvoy, the technical and operations director at the Kalamazoo plant, stated.

Pfizer employees transfer vaccine to a freezer. (Photo: New York Times).

The failure in September 2020 demonstrated that Pfizer was still far from victory. The ambitious goal of vaccine production ultimately forced Pfizer to accept collaboration with the government to secure supplies of essential components for vaccine production, despite previously attempting to avoid collaboration with federal health agencies.

After the technical failure in September 2020, Pfizer experts identified the problem as a faulty filter, causing the lipid nanoparticles to leak out during the filtering process. Pfizer then had to inspect the quality of all filters.

At the production facility in Puurs, Belgium, Pfizer’s production team utilized information obtained from the Kalamazoo plant and successfully conducted a technical trial on September 14, 2020.

However, bulky filters continued to slow down the production process. Pfizer subsequently added more filtering areas, expanded the scale, and doubled the capacity from 1.7 million doses to 3 million doses per production batch.

Later, amid supply shortages, Pfizer invented a system to reuse used filters.

Two Miracles from Pfizer

On November 9, 2020, clinical trial results brought positive signals as Pfizer’s vaccine achieved over 90% effectiveness in preventing Covid-19, raising hopes of ending the pandemic.

However, at that time, Pfizer had to reduce its vaccine production for 2020 from 100 million doses to 50 million doses.

In a subsequent announcement, Pfizer stated that alongside issues in the production process and raw material supply, the delayed clinical trial results left the company with insufficient time to produce as originally promised.

On December 11, 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted emergency use authorization for Pfizer’s vaccine.

On December 13, 2020, the first batches of Pfizer’s vaccine departed from the Kalamazoo plant to federal stockpiles.

As Pfizer’s vaccine demonstrated its potential to be a solution to end the pandemic, the Trump administration requested Pfizer to provide an additional 100 million doses, in addition to the original commitment of 100 million doses.

At this point, the Trump administration, followed by the Biden administration, held what Pfizer desired.

The White House had the authority to activate the Defense Production Act—a law that allows the government to control industrial production during a national emergency—to help Pfizer prioritize access to essential raw materials and equipment needed for vaccine production.

President Joe Biden visiting Pfizer’s manufacturing facility in Kalamazoo. (Photo: Reuters).

By December 22, 2020, former President Trump placed Pfizer on the priority list for lipid purchases under the Defense Production Act. Pfizer subsequently announced it would sell an additional 100 million doses of the vaccine to the U.S. government.

“The reality is they needed help. Allowing other manufacturers to purchase equipment and components (to produce vaccines) would harm Pfizer. We previously used the Defense Production Act to help Moderna buy lipids and assist other companies in acquiring sterile bags. Pfizer would be at the end of the queue for purchasing,” Slaoui stated.

After taking office, the Biden administration announced it would utilize the Defense Production Act to help Pfizer prioritize the purchase of pumps and filters.

Pfizer engineers noted that expanding filtration capacity was crucial in increasing vaccine output.

President Biden personally visited Pfizer’s manufacturing facility in Kalamazoo. There, he toured the freezer equipment, witnessed workers packaging vaccines for shipment to states, and used dry ice produced by Pfizer for cooling.

After the first “scientific miracle” of producing the mRNA vaccine, Pfizer’s success in Kalamazoo was the “second miracle—production miracle—helping to create hundreds of millions of vaccine doses,” President Biden praised Pfizer.