To answer this question in 2016, a research team at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in the United States conducted an experiment: They “kidnapped” sharks living near the California coast, blindfolded them, and then took them out to sea, 9 kilometers away.

The kidnapping was executed literally. The sharks were caught and brought aboard a boat, flipped upside down to induce a state of immobility due to tonic immobility. The scientists covered the sharks with a white tarp to prevent them from orienting themselves using the angle of sunlight.

A total of 26 sharks were divided into two groups. The first group consisted of 11 sharks that had cotton swabs coated with mineral Vaseline inserted into their nostrils before being released into the water. The goal was to see if, when their sense of smell was incapacitated, they could find their way back to shore.

The second group consisted of 15 other sharks, known as the control group. These sharks also had their nostrils plugged, but without the Vaseline, meaning their sense of smell remained intact.

Dr. Andrew Nosal releasing a shark back into the ocean after capturing it.

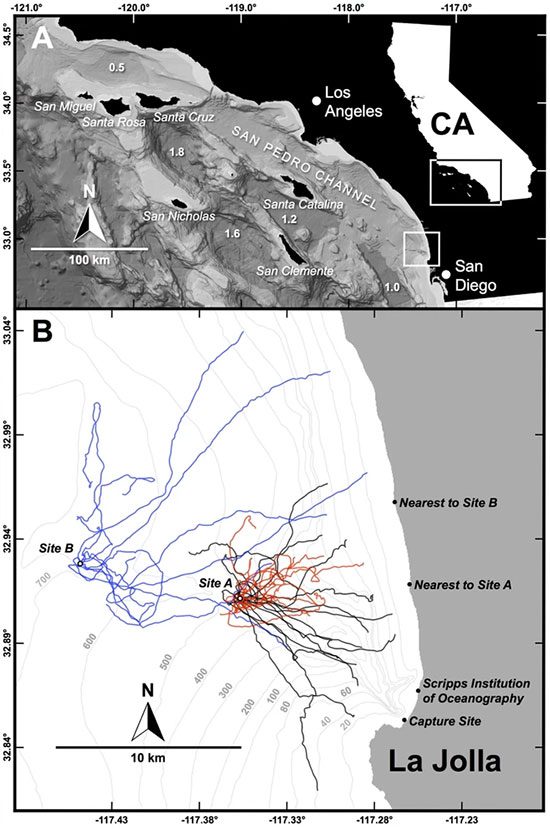

After being released, the scientists used tracking devices to monitor the movements of the two groups of sharks. The results showed that the 15 normal sharks could immediately find their way back to shore. They swam faster than average and returned home nearly in a straight line.

In contrast, the 11 sharks with Vaseline in their nostrils struggled to determine where their home was. They swam slowly and erratically, at half the speed of the normal sharks, with some even getting lost and swimming in circles.

Dr. Andrew Nosal, the lead author of the study, stated: “This experiment demonstrates that olfaction is a crucial factor for sharks to navigate.” Previous studies have also shown that sharks possess a well-developed area in their brains dedicated to olfactory perception.

The hypothesis proposed by Dr. Nosal is that they may rely on gradients in seawater to find their way home. Gradient refers to the gradual decrease in concentration of specific chemical molecules over distance. In simple terms, sharks can smell where their home is located, as their home waters contain specific chemical molecules.

The further they swim in the right direction, the higher the gradient concentration increases, helping sharks know exactly where they need to swim. This gradient orientation mechanism has been previously discovered in birds.

“With the similarities in the three-dimensional flow mechanisms of the atmosphere and the ocean, further studies comparing swimming and flying animals could lead to a unified model explaining their extraordinary navigational abilities,” the research authors noted.

The black and blue paths represent sharks with normal olfaction. The red path represents the sharks with their nostrils plugged with mineral Vaseline.

A shark fitted with a tracking device in the study.

However, the story of sharks’ navigational abilities does not end with their sense of smell. “Olfaction is not the only sense that sharks use to find their way,” Dr. Nosal said.

This is because in the group of sharks with Vaseline in their nostrils, he observed that although they could not swim directly home, they still tended to swim toward the shore.

Previously, scientists had also documented sharks “hitchhiking” across the ocean over unimaginable distances. They certainly could not rely on their sense of smell to navigate in those cases.

For example, in 2005, they observed a massive great white shark swimming all the way from South Africa to Australia. Remarkably, it was able to return home in a straight line.

A similar phenomenon has been found in populations of sharks swimming from Hawaii to California and from the coast of Alaska to the subtropical Pacific region. Bryan Keller, an ecologist at the University of Florida, suspects that this ability in sharks may come from their capacity to sense the Earth’s magnetic field.

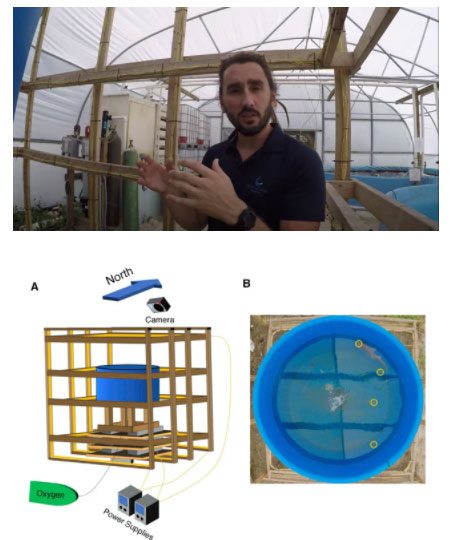

Bryan Keller in his experimental device cage with sharks.

Since the 1970s, scientists have suspected that a group of fish, including sharks, rays, and sawfish, can navigate using the magnetic field. However, no one has been able to prove this to be true for sharks.

Therefore, Keller decided to conduct an experiment. He created a large cage wrapped in copper wire. Then, Keller adjusted the electric current flowing through each coil of copper wire to simulate the Earth’s magnetic field.

Finally, about 20 juvenile sharks were selected, placed in a tank, and brought into the cage. Now, Keller exposed them to three different magnetic environments.

Scenario 1: When the coils of copper wire simulated the actual magnetic field of the Earth at the location where the sharks were caught, he observed that the sharks swam randomly around the tank.

Scenario 2: When the magnetic field was adjusted to mimic a location 600 kilometers south of the sharks’ home, the sharks swam toward the top of the tank, or more specifically, northward.

Scenario 3: Conversely, when the magnetic field simulated a location 600 kilometers north. However, this time Keller did not see the sharks showing a tendency to swim downward in the tank to find their way south.

Explaining this experiment, the research team stated that scenarios 1 and 2 correctly demonstrated that sharks have the ability to use the magnetic field to navigate home.

In scenario 3, this hypothesis still holds true because the sharks they caught are a population that typically migrates south. They do not usually swim north, so they did not know what to do when placed in a virtual location 600 kilometers north of their home.

This further proves that the ability to navigate using the magnetic field is a skill that sharks learn rather than being innate. “The sharks would be confused about what to do in the north because they have never swum there before,” Keller said.

His research and that of his colleagues has just been published in the journal Current Biology. This is significant evidence showing the remarkable navigational abilities of sharks. Among terrestrial animals, dogs also possess the ability to navigate using both olfaction and the magnetic field.

So, if your pet never gets lost on its way home, sharks are the same. They are exceptionally skilled at finding their way.