Never having officially studied medicine, Louis Pasteur is still regarded as a great physician and honored as the “benefactor of humanity.”

Few people have saved as many lives as Louis Pasteur. The vaccines he developed have protected millions. His research on microbes revolutionized medicine. He also discovered new methods to make food safe to eat. The BBC notes that Pasteur completely transformed humanity’s understanding of biology, becoming the “father of microbiology.”

Born on December 27, 1822, in Dole, Jura (France), Pasteur was an ordinary student with a passion for painting. The boy often wandered the streets of Dole, Jura, the village where he was born and raised, sketching portraits of people he wished to meet in his notebook. He once dreamed of becoming an artist. While his teachers encouraged him to pursue art, his father considered it a pastime and wanted him to focus on his studies. Pasteur once said his father wanted him to “absorb the greatness of France” from an early age, hoping he would become a professor. Due to the family’s modest means, his father sacrificed a lot to ensure his son could attend a prestigious school.

At the University of Strasbourg, Pasteur began his chemistry career and quickly made a name for himself. At the age of 25, he made his most significant contribution to science by demonstrating that identical molecules can exist as images in a mirror.

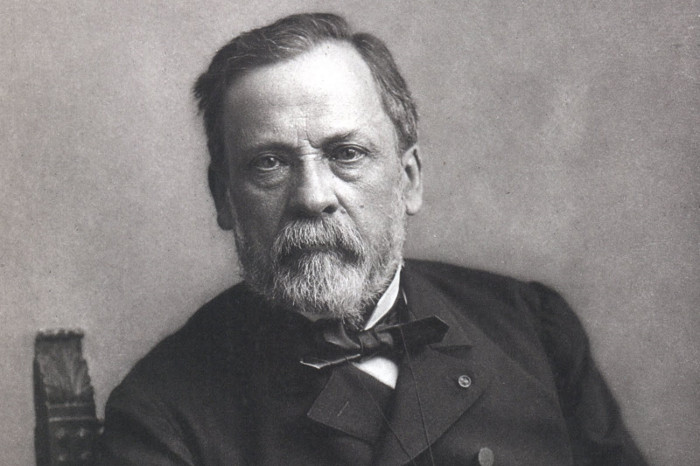

Portrait of Louis Pasteur. (Photo: Nadar).

His chemical research helped Pasteur solve one of the greatest mysteries in biology of the 19th century. For 2,000 years, people believed that life appeared spontaneously, with fleas arising from dust and maggots from dead bodies. Through a standard experiment, Pasteur proved that spoiled food is caused by bacteria in the air. He concluded that these bacteria could cause disease. This theory was controversial as Pasteur was a chemist, not a doctor, but it led to the development of antiseptics, forever changing medicine.

After his germ theory gained attention, Napoleon III tasked him with addressing a problem faced by the French wine industry at the time. French wine, famous throughout Europe, often spoiled during transportation. Pasteur found that this phenomenon was caused by bacteria and that heating the wine to 55 degrees Celsius would kill the bacteria without ruining the wine’s flavor. Today, this process is known as pasteurization, used to protect food from contamination.

Following his work with wine, Pasteur saved the silk industry by discovering that silkworms were suffering from a parasitic disease. His advice to isolate and eliminate infected individuals provided a boost to the French economy. Pasteur’s reputation continued to grow.

At the age of 45, Pasteur suffered a stroke that left him partially paralyzed on his left side. From this point, he immersed himself in work to forget his significant losses. At that time, children often died from infectious diseases. The scientist himself lost three daughters in 1859, 1865, and 1866 to typhoid fever and cancer. Pasteur was so distressed that he exclaimed, “the only thing that can bring joy is work.” Family tragedy became his motivation to begin a battle against infectious diseases.

Initially, Pasteur and his team developed research on chicken cholera. He injected cholera bacteria into a flock of chickens; the animals fell ill but did not die as expected, later developing immunity to the virulent bacteria. Pasteur realized that weakened pathogens could help animals enhance their immunity, creating a breakthrough that built on Edward Jenner’s earlier achievements from a century prior.

Pasteur conceived the idea of developing vaccines for other diseases. He turned his attention to anthrax and claimed to have found a vaccine that was effective on 31 types of animals.

He then continued with rabies, a disease with horrific symptoms leading to prolonged painful death. He met Joseph Meister, a boy bitten by a rabid dog. At that time, no one was certain if Joseph would contract rabies, yet Pasteur boldly decided to test the vaccine on the boy, despite never having administered it to humans before. As a result, Joseph survived. The first human vaccine trial on July 6, 1885, was successful, although it faced criticism that Pasteur violated professional ethics by practicing medicine without a license.

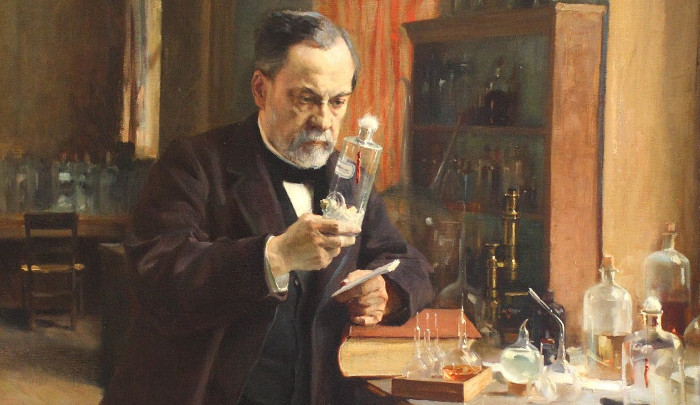

Louis Pasteur in his office. (Painting: A. Edelfeldt).

Pasteur presented his findings on rabies to the French Academy of Sciences on March 1, 1886. On this occasion, he proposed the establishment of a facility to produce vaccines against rabies. In 1887, Pasteur received 2 million French Francs in donations. By 1888, President Sadi Carnot commissioned the construction of the first Pasteur Institute in France, which later expanded to colonies such as Senegal and Côte d’Ivoire. The mission of the Pasteur Institute has remained unchanged since then: to research and develop vaccines and to implement immunization against infectious diseases.

The first significant achievement of the Pasteur Institute was identifying the mechanism causing diphtheria. This work, conducted by Emile Roux and Alexandre Yersin, led to treatment methods and eventually a vaccine. Today, 85% of children worldwide are vaccinated against diphtheria.

Pasteur managed the Pasteur Institute in Paris until his death on September 28, 1895, at the age of 72. The remains of the “national hero” were buried at Notre-Dame Cathedral before being transferred to the Pasteur Institute. In 1940, when Nazi Germany occupied Paris, the gatekeeper of the Pasteur Institute was the boy Joseph, who resolutely refused to open the tomb. Joseph took his own life to ensure that he would never desecrate the remains of his benefactor.

Today, Louis Pasteur is remembered as one of the pioneers of preventive medicine. His work continues to save millions of lives worldwide.

The BBC once stated that Pasteur completely changed humanity’s understanding of biology, becoming the “father of microbiology.”

Pasteur managed the Pasteur Institute in Paris until his death on September 28, 1895, at the age of 72. The remains of the “national hero” were buried at Notre-Dame Cathedral before being transferred to the Pasteur Institute.