By piecing together fragments of an ancient skull, scientists have successfully recreated the visage of a creature they refer to as the “killer tadpole” or “hell tadpole”, which lived 330 million years ago during the Carboniferous period.

The creature, named Crassigyrinus scoticus, has been known and named by scientists for over a decade, but no one had been able to provide a concrete image of its appearance, as all collected fossil fragments were severely crushed.

Appearance of the 330-million-year-old “killer tadpole” – (Photo: UCL).

However, advances in CT scanning and 3D imaging have allowed researchers from University College London (UCL) to successfully conduct a highly intricate “puzzle” assembly, “resurrecting” the ancient creature in a vivid digital portrait, according to Live Science.

They had to use CT scanners to piece together four clusters of shattered fossils from four different individuals to perform the virtual resurrection of the monster.

Previous studies suggested that this creature was a four-legged animal related to the first organisms that transitioned from water to land about 400 million years ago.

However, the latest survey indicates that Crassigyrinus scoticus must have been a water-dwelling animal, and it is likely that its ancestors underwent a reverse transition: While they did venture onto land during evolution, they later decided to return to the water, becoming the rulers of the Carboniferous swamps.

Carboniferous swamps were wetland areas that later became major coal deposits in what is now Scotland and North America.

This virtual “resurrection” also revealed that the creature, measuring about 3 meters in length, had a relatively flat body and short limbs, somewhat resembling a South American crocodile. A size of 3 meters was enormous at that time, as reptiles had not yet evolved to the impressive sizes of the later dinosaur era.

Thus, this beast was indeed a tyrant of its age, with specimens collected dating back up to 330 million years.

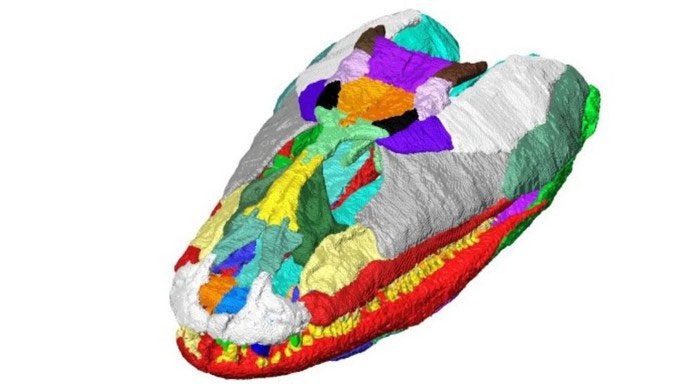

Reconstruction of the creature’s skull – (Photo: UCL).

The reconstructed face also shows that it had large eyes for seeing clearly in murky water, and lateral line organs similar to those of fish, which are sensory systems that help aquatic animals detect small vibrations.

A gap remains in front of the creature’s snout, believed to be the location for attaching organs responsible for another special sense, enhancing its hunting capabilities.

The study has just been published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.