A group of scientists has starved several different groups of bacteria for over two and a half years; however, under conditions devoid of food sources, most of these groups managed to survive, and even thrive fairly well. The researchers argue that this finding suggests that some bacterial populations may be capable of surviving for up to 100,000 years.

Previously, it was widely believed that most bacteria could not survive long in the environment. While this is not incorrect, as individual bacteria can die off quickly in various locations, they become remarkably difficult to eradicate when clustered in large populations. This has been a painful lesson for humanity in the study of the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria over the past few decades. To better understand bacterial resilience, researchers at Indiana University (USA) conducted a special experiment.

Cultivating bacteria.

They collected around 100 different bacterial populations, representing 21 different taxonomic units (a taxonomic unit refers to a broad group, such as a family or genus). They then placed them in an “efficient closed system” where they appeared to have no food source to sustain themselves for 1,000 days. After this period, they opened these “tombs.”

The researchers found that the bacterial populations had declined, particularly in the early stages, but nearly all survived after 1,000 days of starvation. Some groups even stabilized over time, with their “population” remaining relatively unchanged after the first few hundred days. Typically, bacteria will slow their biological processes, meaning they require less energy to live. Some transformed into spores, a nearly dormant form that needs extremely low energy to maintain. However, some bacteria resorted to cannibalism, consuming those that did not survive the initial starvation. According to the scientists, these dead cells were likely a major factor contributing to the overall longevity of the bacteria.

While the experiment lasted only 1,000 days, the research team utilized the rate of decline of these populations over time to theoretically estimate how long they could survive. They concluded that the hardiest bacterial groups in their study could outlive even the oldest known plant and animal species, potentially lasting up to 100,000 years or more. This is particularly impressive, given that bacteria are often characterized by extremely rapid reproduction cycles, which typically come at the cost of shorter lifespans.

“Although bacteria can reproduce in time frames ranging from a few minutes to several hours, we predict that populations could survive for hundreds to thousands of years,” the authors wrote in their study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) this month.

Scientists recently announced they revived 100-million-year-old bacteria.

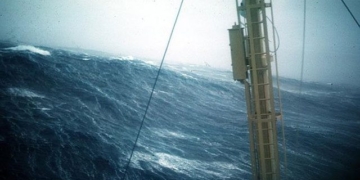

There has been practical evidence of the long-lasting nature of bacteria. Some scientists claim to have found and revived intact bacteria in isolated environments, such as crystalline salt mines or permafrost. The age of these ancient bacteria has been estimated to range from 120,000 years to over 200 million years. Last year, Japanese scientists reported that they revived 100-million-year-old bacteria from seabed sediment samples.

“The bigger question about how bacteria survive for long periods in energy-limited environments relates to understanding chronic infections in humans and other hosts, and how some pathogens tolerate drugs like antibiotics,” said Jay Lennon, a biology professor at Indiana University and author of the study.

The researchers stated that their findings could help inform future studies on how these ancient bacteria escape dormancy and how bacteria, in general, can survive in some of the harshest environments on Earth. This could also prove useful in mitigating the relatively few pathogenic bacterial groups that affect humans.