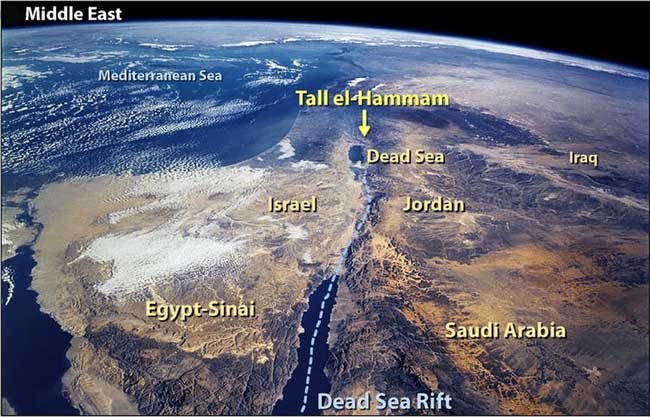

[When the residents of an ancient Middle Eastern city known today as Tall el-Hammam went about their daily tasks on a day roughly 3,600 years ago (in 1650 BCE), they had no idea that an ‘invisible’ icy space rock was hurtling toward them at a speed of about 61,000 km/h (approximately ~17,000 meters per second).

As it streaked through the atmosphere, the rock exploded into a massive fireball about 4,000 meters above the ground. The explosion was equivalent to 1,000 atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima (1945).

The city’s inhabitants stared in shock, with hundreds instantly rendered permanently blind.

The air temperature rapidly soared above 2,000 degrees Celsius. Clothing and wood ignited immediately. Swords, spears, mud bricks, and ceramics began to melt. Almost instantly, the entire city was engulfed in flames.

A few seconds later, a massive shockwave slammed into the city. Moving at a speed of about 1,200 km/h, it was stronger than the worst tornado ever recorded in history [the Tri-State Tornado that struck three states in the U.S.—Missouri, Illinois, and Indiana—on March 18, 1925]. The deadly winds tore apart the city, obliterating every building.

No one among the 8,000 people or any animals in the city survived—their bodies were shredded, and their bones shattered into tiny pieces.

About a minute later, 22 kilometers west of Tall el-Hammam, the winds from the explosion reached the city of Jericho on the eastern bank of the Jordan River. The walls of Jericho collapsed, and the ground was scorched.

All of this sounds like the climactic scene of a Hollywood disaster movie. But this was the reality that occurred nearly 4,000 years ago.

Image depicting the explosion with the power of 1,000 atomic bombs at Hiroshima (Japan). (Photo: Allen West and Jennifer Rice, CC BY-ND).

So how do we know that all these horrific events actually took place near the Dead Sea in Jordan millennia ago?

Answering this question required nearly 15 years (since 2006) of tireless excavations by hundreds of archaeologists, scientists, and historians, along with volunteers from across North and South America, Europe, Africa, Asia, Australia, New Zealand, and the Near East.

The answer also involved detailed analyses of excavated materials by over 20 scientists in 10 U.S. states, as well as Canada and the Czech Republic. In summary, the disaster picture we just witnessed is the result of the efforts of hundreds of scientists working over 15 years.

When the group of scientists published evidence of the meteor explosion that killed thousands 3,600 years ago at Tall el-Hammam in the journal Scientific Reports, 21 co-authors collaborated on this report. They included archaeologists, geologists, geochemists, geomorphologists, mineralogists, paleontologists, sedimentologists, impact experts, and medical doctors.

This is how they constructed the picture of this terrible devastation in the past.

Destruction Layer

Many years ago, when archaeologists observed the excavations of the ruined city, they could see a thick layer about 1.5 meters of charcoal, ash, melted mud bricks, and melted ceramics.

It was clear that a fierce firestorm had destroyed this city long ago. This dark band is referred to as the destruction layer.

The 1.5-meter-thick destruction matrix also exhibited rare characteristics not found in the strata above or below it.

Researchers at the ruins, with the destruction layer located between each wall. (Photo: Phil Silvia, CC BY-ND).

No one is sure exactly what happened, but that layer was not caused by a volcano, earthquake, or war. None of these disasters could melt metals, mud bricks, and ceramics to such an extent.

To find out the culprit and what truly occurred, the team of scientists used the Earth Impact Program to model scenarios that matched the evidence. Developed by impact experts, this computational method allows researchers to estimate many details of a cosmic impact event, based on known collision events and nuclear explosions.

It appears that the culprit at Tall el-Hammam was a small asteroid similar to the one that devastated 80 million trees in Tunguska, Russia, in 1908. And the culprit at Tall el-Hammam was a much smaller version of the gigantic asteroid that struck Earth and wiped out the dinosaurs 65 million years ago.

Thus, scientists had a “suspect.” Now it was time for them to seek evidence of what happened that day at Tall el-Hammam.

Searching for Diamonds in the Dirt

The scientists’ research revealed a significant array of evidence.

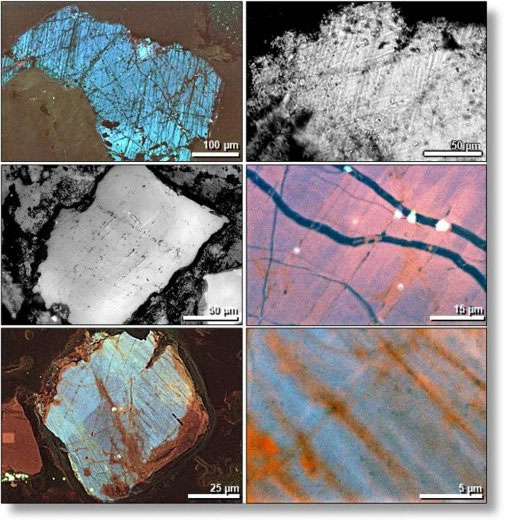

In this area, there are fine cracked sand grains known as shock quartz, which only forms under pressures of 725,000 pounds per square inch (5 gigapascals)—If you can’t visualize how big 5 gigapascals is, imagine that pressure being equivalent to 6 U.S. M1 Abrams main battle tanks weighing 68 tons each stacked on top of your thumb!

Electron microscope image of numerous small cracks in shock quartz grains. (Photo: Allen West, CC BY-ND).

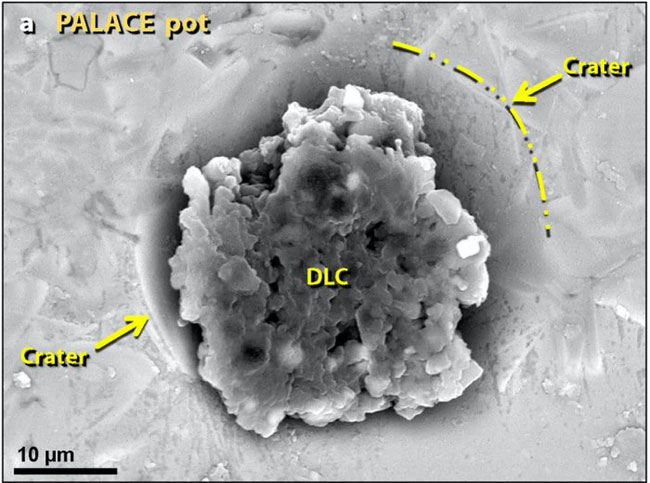

The destruction layer also contained small diamonoid particles – Nanodiamonds – which, as the name suggests, are as hard as diamonds.

According to the initial assessments by scientists, it seems that the wood and vegetation in the area were instantly transformed into this diamond-like material due to the tremendous pressure and high temperature of the fireball.

Diamonoid (center) formed due to high temperatures from the fireball and pressure on vegetation. (Photo: Malcolm LeCompte, CC BY-ND).

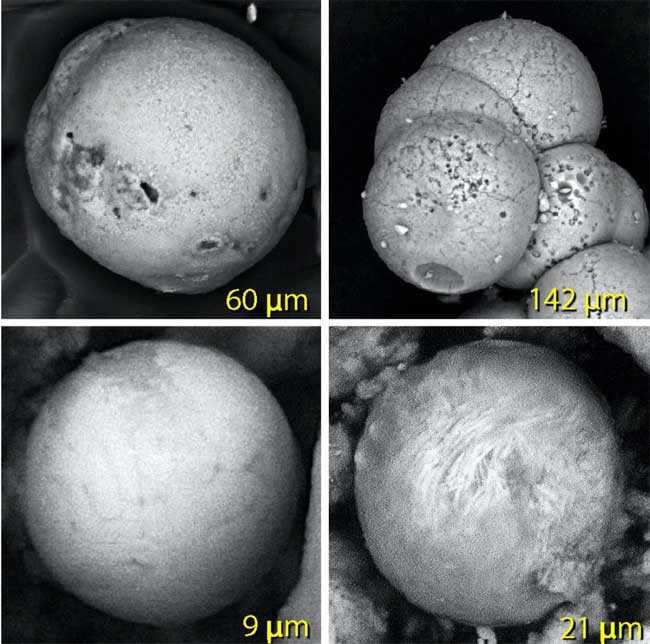

Laboratory experiments with furnaces showed that the bubbly ceramics and mud bricks at Tall el-Hammam melted at temperatures above 1,500 degrees Celsius. It was hot enough to melt a car within minutes.

Molten sand sphere (top left), plaster mortar (top right), and molten metal (two images below). (Photo: Malcolm LeCompte, CC BY-ND).

The destruction layer also contained materials smaller than dust particles in the air. Known as microspheres, they were made of iron and molten sand at around 1,590 degrees Celsius.

Additionally, the surface of the ceramics and molten glass was speckled with tiny melting metal particles, including iridium with a melting point of 2,466 degrees Celsius, platinum melting at 1,768 degrees Celsius, and zirconium silicate melting at 1,540 degrees Celsius.

Together, all this evidence suggests that the temperatures in the city rose higher than those of volcanic eruptions, warfare, and typical urban fires. The only remaining natural process is a cosmic impact.

Similar evidence has also been found at known impact sites, such as the Tunguska event (Russia) and the Chicxulub crater (on the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico), created by an asteroid crashing into Earth.

This discovery raises the question of why the city and over 100 other settlements were abandoned in the centuries following this devastation?

According to scientists, the cause may be due to high salt deposits after the impact event, making it impossible for crops to grow.

“We are not certain, but we think that the explosion may have vaporized or scattered the toxic Dead Sea saltwater throughout the valley. Without crops, no one could live in the valley for up to 600 years, until minimal rainfall in this desert-like climate washed the salt off the fields,” the authors wrote in the report.

Living Witness?

This terrifying aerial destruction event has been passed down orally through generations until it was recorded as the story of Sodom in the Bible. The Bible describes the destruction of an urban center near the Dead Sea—fire and brimstone raining down from the sky, causing more than one city to be destroyed, thick smoke rising from the flames, and the city’s inhabitants perishing.

The trajectory of the meteor exploding in the sky over present-day Tall el-Hammam. (Photo: NASA, CC BY-ND).

Could this be the account of an ancient witness?

If this is true, the destruction of Tall el-Hammam may be the second oldest annihilation of a human settlement caused by a cosmic impact event, following the village of Abu Hureyra in Syria around 12,800 years ago.

What is frightening is that, according to scientists, a meteorite impact on Earth is almost certainly not the last time it will happen, resulting in human casualties and leaving scars on the Earth from extraterrestrial forces.

Explosions of gas similar in size to meteorites, such as the event that occurred at Tall el-Hammam, can devastate entire cities and regions, posing an extremely serious threat in modern times.

An animated image depicting the positions of known near-Earth objects over 20 years, as of January 2018. (Image: NASA / JPL-Caltech)

As of September 2021, there are over 26,000 known near-Earth asteroids and a hundred short-period near-Earth comets. One of them is certain to collide with Earth. Millions of other meteoroids remain undiscovered, and some may be heading toward Earth right now.

Unless telescopes in orbit or on the ground detect these potential hazardous objects, the world may have no warning, similar to the people of Tall el-Hammam who suffered a disaster from the sky in the literal sense.

According to scientists, meteorites colliding with Earth are among the global-scale disasters that threaten human life and other living beings, alongside nuclear war and climate change.

This article was co-authored by archaeologists Phil Silvia, geophysicist Allen West, geologist Ted Bunch, and astrophysicist Malcolm LeCompte.

Co-author Christopher R. Moore is an archaeologist and Director of Special Projects at the Savannah River Archaeological Research Program and the South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina, USA.