As of September 30, 1991, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that 163 countries and territories had identified AIDS patients, with the number of infected individuals reaching 410,000. Experts from the WHO estimated that the actual number of people infected worldwide was around 1.1 million, projected to rise to approximately 40 million by the end of the 20th century.

In 2005, Vietnam had about 260,000 people living with HIV/AIDS. In the first half of 2005, the country reported 6,704 new HIV cases, including 1,377 AIDS patients and 670 deaths due to AIDS.

In 2005, Vietnam had about 260,000 people living with HIV/AIDS. In the first half of 2005, the country reported 6,704 new HIV cases, including 1,377 AIDS patients and 670 deaths due to AIDS.

In mid-1986, the WHO decided to officially designate AIDS as “Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome,” abbreviated in English as HIV, indicating that the HIV pathogen was latent and developing slowly in the body, leading to the disease outbreak.

In 1988, to call for global cooperation against the deadliest epidemic in human history, the WHO established December 1st as “World AIDS Day.”

In May 1983, a research team from the Pasteur Institute in France isolated AIDS pathogens from the lymph nodes of HIV-infected individuals, marking the first time humanity identified the virus causing AIDS.

In April 1984, a research group led by Robert Gallo at the U.S. National Cancer Institute also isolated the AIDS pathogen from a “T” cell culture system of AIDS patients, marking a significant breakthrough in medical research against AIDS.

Since then, AIDS has become increasingly widespread. However, it was not until recently that a medical record of the earliest known AIDS patient was discovered: a sailor from Manchester, England. In 1959, this 25-year-old sailor suffered from a bizarre illness: excruciating skin pain, persistent high fever, severe lung infection, and rapid weight loss. Shortly after being hospitalized, he passed away. The unusual symptoms raised suspicions among the doctors, who performed an autopsy and discovered that the patient’s lungs were infected with a type of parasite, causing numerous small holes. At that time, medical science lacked understanding of AIDS, so the doctors merely published the symptoms in a medical journal and preserved some of the patient’s organs at the Manchester hospital.

By 1983, after French medical researchers announced their findings on the AIDS pathogen, specialists from the University of Manchester analyzed some of the preserved organs of the aforementioned patient: kidneys and pancreas, eventually discovering the characteristic symptoms of AIDS. They concluded that AIDS had been present since the mid-20th century and that the disease had already begun transmitting the HIV virus. This indicated that Western countries, at the latest, had patients suffering from AIDS by that time.

By 1983, after French medical researchers announced their findings on the AIDS pathogen, specialists from the University of Manchester analyzed some of the preserved organs of the aforementioned patient: kidneys and pancreas, eventually discovering the characteristic symptoms of AIDS. They concluded that AIDS had been present since the mid-20th century and that the disease had already begun transmitting the HIV virus. This indicated that Western countries, at the latest, had patients suffering from AIDS by that time.

After ten years of research, experts and scholars concluded that the AIDS pathogen may have existed 50 to 150 years ago. Subsequently, the pathogen began to mutate and spread. After more than a century of development, it has now become a deadly and unprecedented epidemic. Today, the world faces rapid transmission and increasingly alarming mortality rates. AIDS is often referred to as the “disease of the 20th century.”

But where did this unprecedented disease in human history originate?

Initially, it was observed that AIDS patients were predominantly among homosexuals and individuals engaging in promiscuous sexual behavior in major U.S. cities. This led to the belief that homosexuality, seen as contrary to natural laws, was a source of sexual chaos resulting in unforeseen diseases, including AIDS. However, extensive research by many scientists revealed that homosexual behavior has been present in Western societies since ancient Greece and Rome, and similar issues existed in Eastern countries in ancient times. If homosexuality was the cause of AIDS, the disease would have circulated since antiquity; why then did it only spread recently? This led to the conclusion that homosexuality is not the origin of AIDS, but it is a highly dangerous transmission route for the disease.

Scientists have proposed several theories regarding the origin of AIDS:

– One: The hypothesis of extraterrestrial transmission to Earth. This view was first presented by two British scientists who suggested that the AIDS pathogen has long existed in the universe. For thousands of years, it remained untransmitted to Earth due to the absence of a vector, until a comet collided with the planet, bringing the pathogen with it and harming humanity.

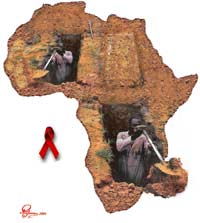

– Two: The hypothesis that monkeys transmitted the pathogen to humans. Researchers found that some primates in Africa harbor pathogens similar to those of AIDS patients. Studies showed that the transmission of these pathogens in Africa preceded that in Europe and America, with estimates suggesting that up to 10% of the population in major Central African cities may carry the AIDS pathogen. In the 1980s, a study in Kinshasa, Zaire, found that 6-7% of 1,000 blood samples tested positive for the AIDS pathogen.

In Zambia, by 1987, around 6,000 children were treated for AIDS. In some regions of Africa, up to 5% of newborns carry the AIDS pathogen, with half to two-thirds likely to develop AIDS within one to two years. During the strong spread of AIDS around the Great Lakes region of Central Africa, a French research worker discovered that some local tribes practiced a peculiar custom: they injected the blood of male and female monkeys into men and women to enhance sexual arousal. Some even used this method to treat infertility and impotence. Given the blood contact that could transmit the AIDS pathogen, alongside the high infection rates and this unusual blood-injection custom, researchers hypothesized that AIDS was transmitted from monkeys to humans. The history of this blood-injection practice among certain Central African populations likely predates the history of AIDS, leading researchers to propose that monkeys may have transmitted the AIDS pathogen to humans long ago, but due to random natural cycles, it was self-limiting and went unnoticed. In modern times, with many Europeans and Americans traveling to Africa, including promiscuous individuals who brought the AIDS pathogen back to Europe and America, combined with reckless sexual practices and drug use, AIDS spread even further.

– Three: The theory of “human-engineered pathogens.” This claim emerged from media reports. In the mid-1980s, the Tanzanian government newspaper “Daily News” reported that AIDS was a product of U.S. biological warfare research. Later, a British source cited a reliable newspaper stating that the UK opposed the views of the Society for the Study of Living Anatomy. Members of this society claimed that AIDS was created through genetic manipulation in a biological warfare research center. They suggested that the U.S. began research during the Vietnam War to develop a new type of biological weapon.

The initial experiments were conducted on green monkeys in Central Africa, later shifting to trials on voluntarily participating death-row inmates, many of whom were homosexuals. After their release, these individuals unknowingly spread AIDS into society, leading to widespread transmission through various channels. This was an unforeseen consequence for both the test subjects and the researchers. It can be said that this was part of a biological warfare research experiment, which was ultimately abandoned due to the pathogen’s long incubation period and unsatisfactory results. Following these reports, many countries and territories have been mentioned in the media, leading to widespread speculation and public discourse. U.S. authorities have denied these claims, but in some African countries, media reports have linked the U.S. to having the highest number of AIDS cases in the world, affirming this connection.

Despite significant advancements in AIDS research, the exact origins of the disease remain unknown. Clarifying the true source of AIDS is of immense significance for medical science and humanity as a whole.