As human civilization progresses and the population surges daily, environmental degradation follows suit. From household sanitation to human dietary habits, everything is no longer as “pure” as it once was.

Animals that can spread diseases, such as rats, bats, and lice, proliferate alongside humans. The open trade between nations has paved the way for a series of horrific epidemics. Among them is the plague – “The Black Death” of humanity.

The Mysterious Appearance of Two Comets

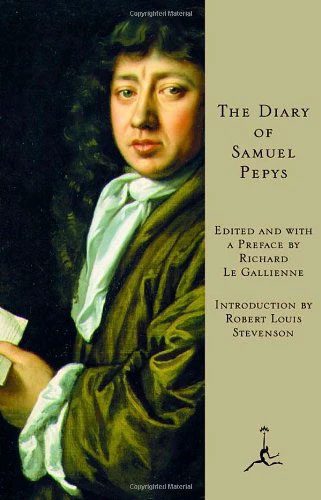

Member of Parliament Samuel Pepys, a leader of the English Navy, is renowned worldwide for his diaries.

Samuel Pepys’ diary is considered a valuable historical document regarding the plague.

He meticulously recorded three of the most significant events in English history: the plague of 1665-1666, the Great Fire of 1666, and the Anglo-Dutch War from 1665 to 1667.

In his diary, he mentioned two comets that appeared in the sky over London. One comet appeared at the end of 1664 and the other at the beginning of 1665. At that time, astrologers believed these were signs of impending doom for England. Little did they realize that these celestial events were not harbingers of evil but rather the “death-bringer” named plague, preparing to claim not only the lives of the English people but also those across Europe.

The Origins of the “Black Death”

Three of the deadliest pandemics recorded were caused by a type of bacterium known as Yersinia pestis, or plague bacteria.

The first plague outbreak is believed to have occurred around 541 AD in Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire (modern-day Turkey). The disease then spread throughout Europe, Asia, North Africa, and Arabia, killing an estimated 30 to 50 million people, about half of the population at the time.

Eight hundred years later, the plague returned and devastated Europe during the “Black Death.” Specifically, in October 1347, when 12 ships from the Black Sea docked at the port of Messina in Sicily, the residents encountered a horrifying sight. Most of the sailors on board were dead, and the survivors were gravely ill, their bodies covered in black, oozing sores.

The Sicilian authorities quickly dispatched a fleet of “death ships” out of the port, but it was too late. The plague spread rapidly, claiming the lives of 200 million people, equivalent to 60% of Europe’s population and 33% of England’s.

According to some opinions, lice and fleas are believed to be carriers of the Yersinia pestis bacteria found in squirrels, rabbits, rats, and chickens. After decimating a large number of rodents, fleas and lice would seek new hosts, which turned out to be humans.

A painting depicting the plague. (Photo: Getty Images)

When there were “no more hosts to infect”, it was thought that the disease would also “die off.” However, ten years later, from 1348 to 1665, there were 40 outbreaks over 300 years in London. Each outbreak saw 20% of men, women, and children perish from this horrific disease.

By the early 1500s, England implemented its first laws requiring the quarantine and isolation of the sick. Families afflicted by the disease would be marked with a bundle of grass hung on a stick outside their homes. If anyone had a relative with the plague, they were required to carry a white stick in public.

By 1665, this was the final outbreak of the plague, yet it was one of the worst, lasting for centuries and resulting in the deaths of 100,000 people in the capital within just seven months.

Samuel Pepys wrote in his diary in August 1665, describing a trip to Greenwich: “Along the way, I saw a coffin with a corpse inside, dead from the plague, in a field belonging to the Coome estate. Perhaps the body was thrown there last night, and the parish did not appoint anyone to bury it. Instead – how cruel – they assigned someone to guard it day and night, warning no one to approach, even the deceased’s family. This plague has made us more brutal to each other than even dogs…”

All forms of entertainment were prohibited at that time, and patients were forced to stay indoors. Although the practice of “imprisoning” the sick in their homes and burying the dead in mass graves was considered barbaric, it was the only way at that time to bring an end to the final outbreaks of this deadly disease.

The Strange Uniform of the “Death Doctors”

In desperation due to the epidemic, European countries established a plague doctor corps.

They did not need formal medical training or much experience; they just had to be courageous individuals willing to enter the epidemic zones to count the dead rather than treat the sick.

For a long time, no one knew the exact cause of “The Black Death,” leading the public to believe in demonic forces, and even the medical community blamed it on “miasma theory.” This meant that the plague was thought to spread through the foul smell of dead bodies.

A painting of a plague doctor in the 17th century. (Photo: Paul Fürst/Death Scent).

This led to the creation of a peculiar protective outfit worn by doctors, becoming an iconic representation associated with “The Black Death.”

The outfit was invented in 1619 by Charles de l’Orme, the chief physician to King Louis XIII of France. It consisted of a long cloak reaching the ankle, baggy trousers, shoes, a hat, and gloves, all made of goat leather infused with fragrant substances and coated with a layer of hard white animal fat to prevent the bodily fluids of the victims from seeping through.

Accompanying the protective outfit was a beak-shaped mask with a “15 cm long nose” filled with herbs like cloves, mint, camphor, and aromatic resins, intended to mask the smell of decay. The eye openings were covered with glass.

When performing their duties, doctors often carried a long wooden stick to examine corpses without making contact or to ward off others, ensuring they kept their distance.

Unfortunately, this outfit, likened to that of the Grim Reaper, proved ineffective in preventing the transmission of the plague. It even caused wearers to feel hot, suffocated, and unable to sweat. As a result, many doctors contracted the disease and died.