The ancient culture of China is largely reflected through cultural relics that prominently bear historical marks from various eras.

Scholars during the Qing Dynasty even claimed that the reliability of historical texts is low, and only the historical values reflected through excavated cultural artifacts are deemed trustworthy. Although this view is quite extreme, it also demonstrates a unique and rigorous academic attitude. Historical texts can be distorted, cultural relics on the surface can be forged, but cultural artifacts excavated from underground hold the highest scientific value and authenticity. The tomb of the emperor is a testament to this.

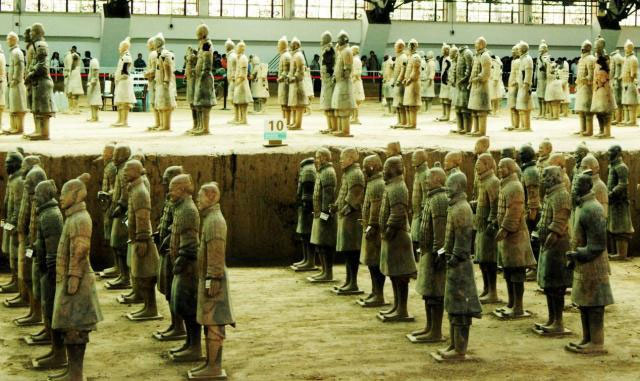

While China has unveiled the famous Terracotta Army to the world, the main tomb of the Qin Dynasty emperor remains shrouded in mystery to this day.

Most inherited artifacts come from ancient tombs, which is not surprising in China. Almost everywhere in the country, there are museums displaying artifacts, complete with details of their excavation sites. Some places have even expanded ancient tombs into scenic spots, many of which are tombs of ancient emperors.

Among them, if we are to mention the tomb of the most famous emperor, there is no doubt that it is Qin Shi Huang. However, despite unveiling the Terracotta Army to the world, the main tomb of the Qin Dynasty emperor has yet to reveal its secrets.

The location of the emperor’s tomb is not a secret; it has been maintained and protected in the past, or it might have been sought after by grave robbers. After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, historian and cultural education expert Guo Moruo repeatedly sought permission to excavate the emperor’s tomb to uncover the truth, but his requests were denied. A cultural relic thousands of years old is indeed too precious and fragile; any slight negligence could cause more damage than that inflicted by tomb raiders.

The actual area of Qin Shi Huang’s tomb is nearly a hundred times larger than that of the Forbidden City, approximately the size of a county in China. Meanwhile, the area where the famous terracotta warriors and horses are buried, known as the “Eighth Wonder of the World”, is merely a burial section of this vast tomb complex.

According to historical records and field surveys, the construction of Qin Shi Huang’s Tomb involved 800,000 laborers, which is eight times more than what was required to build the famous Pyramids. Its size is nearly a hundred times that of the Forbidden City, roughly equal to a county in the country. Therefore, experts have reason to believe that beneath it lies not just an emperor’s tomb, but a complete city.

The cultural relics and historical artifacts from the Qin Dynasty discovered thus far are quite limited. While we know that a significant portion was certainly destroyed by Xiang Yu and others, it cannot be that few remain. This only adds to the layer of mystery surrounding the truth about the Qin Dynasty.

Qin Shi Huang was not a simple king; according to historical records, he was a conservative and eccentric ruler. However, the cultural relics and historical artifacts from the Qin Dynasty discovered to date are quite scarce. Experts speculate that many cultural artifacts did not perish but were buried with their owners.

Among these cultural relics, at least four items will undoubtedly be included in the national treasure list.

Tai A Sword

The Tai A Sword is considered the “sword of dominion” in legend, and many ancient texts record it as the personal sword of Qin Shi Huang. Scholars even have reason to believe that after fleeing from an assassin from the state of Yan, Qin Shi Huang drew this sword and injured Jing Ke. Most of the “Ten Famous Swords” that are known today have lost their trace. This Tai A Sword is probably the only sword that can be definitively traced back to its origin, and it is highly likely that it was one of the first items buried with Qin Shi Huang.

The Tai A Sword is considered the “sword of dominion” in legend, and many ancient texts record it as the personal sword of Qin Shi Huang. (Illustrative image).

Ancient artisans possessed extraordinarily skilled metalworking techniques. A prime example is the pair of battle weapons, the Jiu Jian Sword (King Goujian of Yue) and the Fu Chai Spear (King Fu Chai of Wu), which remain sharp and bright even after thousands of years. Such durable weapons could still be crafted in distant places like Wu and Yue, let alone a “divine weapon” like the Tai A Sword. Through this sword, we can explore the remarkable achievements of artisans during the Qin Dynasty in metalworking and bronze casting.

The Twelve Golden Men

The Twelve Golden Men – 12 bronze human figures were famously mentioned in the work “Discussion on the Qin” in this country’s educational curriculum. According to historical records, after Qin Shi Huang unified the nine provinces, fearing enemies would wage war and foreign nations would create turmoil, he ordered the confiscation of all copper in the country and subsequently cast 12 large bronze human figures in the capital, Xianyang. In ancient times, bronze was also referred to as gold, which is why they are called the 12 golden figures. The 12 bronze figures were said to resemble the Di Ren, a minority ethnic group from the north at that time.

The 12 bronze figures were said to resemble the Di Ren. (Illustrative image).

This indicates that the Qin king was conscious of promoting the process of national integration and no longer distinguished between tribes, aiming to create a completely new nation. However, the 12 bronze figures subsequently went missing. Some say that these figures were melted down for coins by later generations. However, many believe that they are still hidden beneath the tomb, like loyal guards to the emperor.

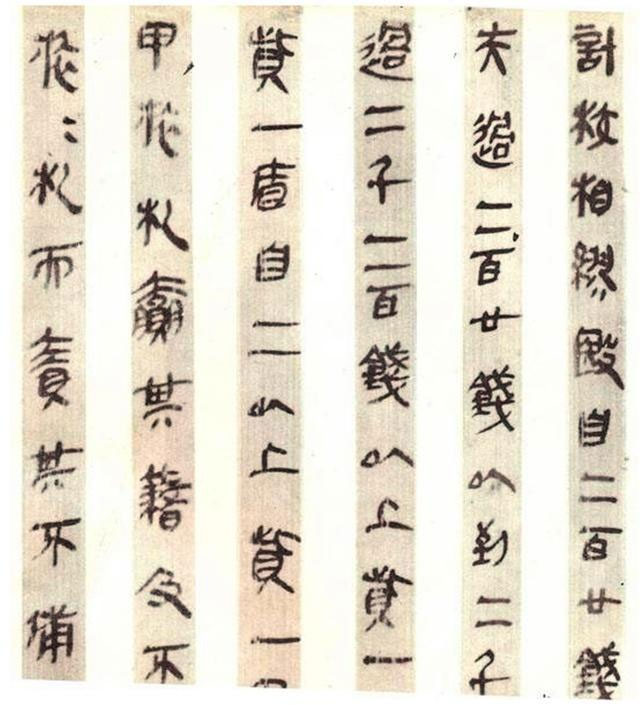

Classical Texts

Valuable cultural artifacts excite experts, but what they truly want to see are the classical texts they have never encountered. After all, ancient manuscripts may contain much more information, making it easier for scholars to understand ancient historical events.

According to records, Xiang Yu burned many valuable books in the Qin palace. These texts documented the historical and local cultural narratives of the time. This act has been criticized by later generations. Qin Shi Huang was not an exceptional figure in literature and art, but he was a “legislator,” who established rules for a thousand years. Is it possible that, in his eternal slumber, a copy of these texts designated by the emperor was buried with him in the tomb?

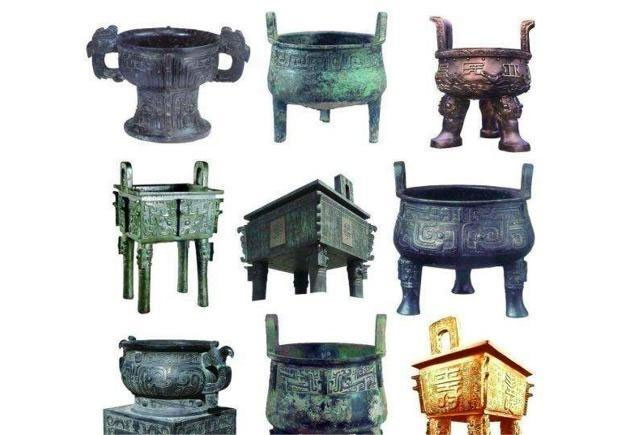

The Nine Tripods

Tripods (ancient cooking vessels made of metal, with three legs and two handles) were originally used for cooking but gradually became the most revered ceremonial items. Tripods were the most representative bronze products and also held the greatest value in ancient times.

According to legend, in ancient times, King Yu the Great divided the realm into nine provinces, then cast nine tripods, engraving the terrain of each province onto each tripod. From there, tripods became associated with the nation and directly represented royal authority. Dynasties came and went, but the nine tripods retained their supreme status in each dynasty. In the past, when King Zhuang of Chu asked King Wen of Zhou about the weight of the nine tripods he possessed, it implied his intention to replace King Wen. It can be said that the nine tripods symbolize the prosperity of the Xia, Zhou, and Shang dynasties.

Dynasties came and went, but the nine tripods maintained their supreme status in each dynasty.

After the downfall of the Eastern Zhou dynasty, the whereabouts of the nine tripods became unknown. Some say they were moved elsewhere, while others claim they sank underwater. Many believe that the nine tripods ended up in the state of Qin. If we assume that the nine tripods were not used to cast the twelve golden men, and if they still exist in the world, they are likely hidden within the Qin tomb.