After a long time submerged in the sea, the wreck has become a habitat for a diverse and structurally complex community of organisms.

Researchers have discovered 114 species of marine animals living in the wreck of an ancient warship off the coast of Sicily, Italy, as reported by Mail on December 30. The ship from Carthage sank on March 10, 241 BC, during a naval battle near the Aegadian Islands in the northwest waters of Sicily. At that time, the Roman Republic’s forces defeated the Carthaginian fleet, marking the end of the First Punic War.

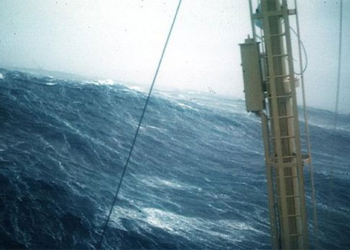

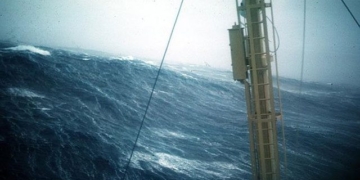

The bow of the Carthaginian warship that sank over 2,000 years ago near Sicily. (Photo: K. Egorov).

The sharp bow of the ship nicknamed Egadi 13 was discovered in 2017 at a depth of about 90 meters by a team of marine archaeologists from the Sicilian Regional Sea Management Agency and divers from the Global Underwater Explorers organization. New analyses reveal a thriving marine life on it.

“Wrecks are often studied to track the invasion of marine organisms, but it is rare to focus on ships that sank over a century ago,” said Dr. Sandra Ricci at the Institute for Conservation Research (ICR).

Ricci and her colleagues found a diverse and structurally complex community with 114 species of invertebrates. Among these were 33 species of gastropods, 25 species of bivalves, 33 species of polychaete worms, and 23 species of bryozoans.

“We infer that the main ‘builders’ in this community are organisms such as polychaete worms, bryozoans, and some bivalve species. The tubes, shells, and clusters of individuals attach directly to the wreck’s surface,” co-author Edoardo Casoli, a researcher at Sapienza University, noted.

“Other species act as ‘glue’: clusters of individuals form bridges between the structures created by the builders. Then, there are ‘residents’ that do not attach but move freely between the cavities in the upper structure. However, we do not yet know the exact order in which these organisms invade the wreck,” Casoli added.

Newer wrecks often have less diverse communities compared to their environments, primarily consisting of species with long larval stages that can disperse widely, according to Dr. Maria Flavia Gravina, a member of the research team. In contrast, Egadi 13 represents a much better natural environment. It contains a diverse community of species with both long and short larval stages, reproducing sexually and asexually, with some adults being highly mobile and others more sedentary, living in schools or solitary.

“We have demonstrated that ancient wrecks like Egadi 13 can serve as a new sampling tool for scientists, acting as an ‘ecological memory’ of the process of animal invasion,” Gravina stated.

Egadi 13 was made from a single block of bronze and features an undeciphered inscription in Punic – the ancient language of the Carthaginians that only existed in the Mediterranean. This sharp bow measures over 60 cm in length, approximately 2.5 cm thick at the front edge, and weighs nearly 170 kg. Due to its hollow structure, organisms and sediments have accumulated both inside and outside.