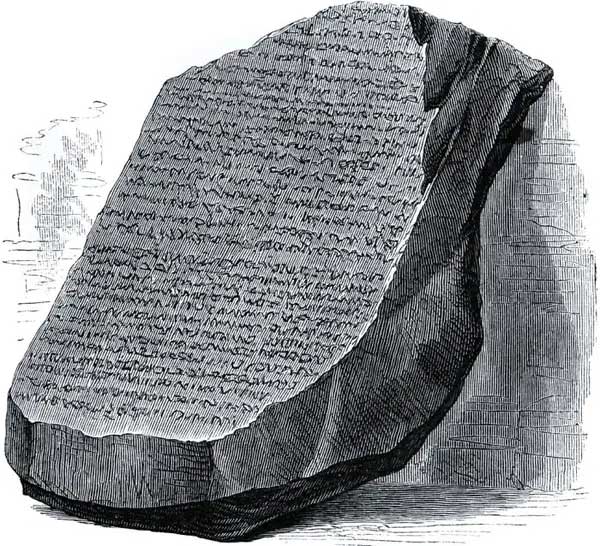

Some ancient societies had writing, but deciphering their texts can be a Sisyphean task. So how do experts find a way to translate ancient words into modern terms? According to researchers, it took 20 years to fully translate the inscriptions on the Rosetta Stone.

Deciphering the Rosetta Stone

The deciphering of the Rosetta Stone, discovered by a French military expedition in Egypt in July 1799, paved the way for understanding Egyptian hieroglyphs.

The stone contains the decree of Ptolemy V inscribed in three writing systems: Egyptian hieroglyphs, Demotic script (used by Egyptians from the 7th century BC to the 5th century AD), and Ancient Greek. Written in 196 BC, the decree states that the Egyptian priests agreed to crown Pharaoh Ptolemy V in exchange for a tax reduction. At that time, Egypt was ruled by a dynasty descended from Ptolemy I, one of Alexander the Great’s Macedonian generals.

The Rosetta Stone.

At the time the stone was discovered, both hieroglyphs and Demotic script had not yet been deciphered, but Ancient Greek was known. The fact that the same decree was preserved in three languages meant that scholars could read the Greek portion of the text and compare it with the hieroglyphic and Demotic sections to identify corresponding parts.

“Although copies of the Rosetta inscription circulated among scholars since its discovery, it would… not be simple to understand,” said Andréas Stauder, a professor of Egyptology at École Pratique des Hautes Études in Paris.

James Allen, a professor of Egyptology at Brown University, noted that hieroglyphs contain signs representing sounds and other signs representing ideas (similar to how today people use a heart symbol to represent love).

Until scholar Jean-François Champollion (1790-1832) began studying hieroglyphs, scholars basically believed that “all hieroglyphs were purely symbolic,” Allen said. He noted that Champollion’s most significant contribution was recognizing that they could also represent sounds.

Because Champollion knew Coptic – the final stage of ancient Egyptian language, written in Greek letters – he was able to deduce the phonetic values of the hieroglyphs from the correspondence between the Egyptian hieroglyphs and the Greek translation on the Rosetta Stone.

Margaret Maitland, the main curator of Ancient Mediterranean at the National Museum of Scotland, stated: “Champollion’s knowledge of Coptic allowed him to see the connection between the ancient symbols he was studying and the sounds he was familiar with from Coptic words.”

Maitland added: “Champollion studied Coptic alongside Yuhanna Chiftichi, an Egyptian priest based in Paris.”

Three Deciphering Challenges

While Egyptian hieroglyphs were deciphered in the 19th century, there are still several ancient languages that remain understood today.

Allen explained: “There are essentially three types of deciphering problems. The hieroglyphs of Egypt fall into the category of ‘known language, but not the script.’ In other words, scholars knew the ancient Egyptian language from Coptic, but did not understand what the hieroglyphic signs meant.”

He mentioned another deciphering issue as “known writing, but not the language.” “For example, Etruscan, which uses the Latin alphabet, and Meroitic, which uses a writing system derived from Egyptian hieroglyphs. In this case, we can read the words, but we don’t know what they mean,” Allen said. (The Etruscans lived in what is now Italy, and the Meroitic people lived in northern Africa).

The third deciphering problem is “both the writing and the language are unknown,” Allen noted, pointing out that an example of this is the script of the Indus Valley from what is now Pakistan and northern India, as scholars do not know what the script is or the language it represents.

Connecting Languages Together?

There are several lessons that scholars studying undeciphered scripts can learn from the deciphering of Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Researcher Stauder stated that being able to relate an undeciphered script to a language or language family is crucial. Champollion needed to know Coptic to understand Egyptian hieroglyphs. Stauder noted that scholars who decipher ancient Maya glyphs use knowledge of modern Maya languages while decoding the characters.

Stauder suggested that scholars trying to decipher Meroitic are making more progress now that they know it is related to the Northeast Sudanese language family.

Stauder stated: “Further deciphering of Meroitic is now greatly aided by comparisons with other languages from Northeast Sudan and reconstructing significant portions of the proto-Northeast-Sudan vocabulary based on the spoken languages of that family.”

Maitland agreed that, “languages that still exist but are currently endangered could prove crucial for advancing the development of ancient scripts that remain undeciphered.”