John A. Larson introduced the lie detector in 1921, but he himself had doubts about its accuracy.

In ancient China, to catch a liar, the accused would sometimes be forced to hold a mouthful of uncooked rice during interrogation, and then asked to open their mouth. Dried rice indicated a dry mouth, which was seen as evidence of guilty anxiety—sometimes even serving as grounds for execution.

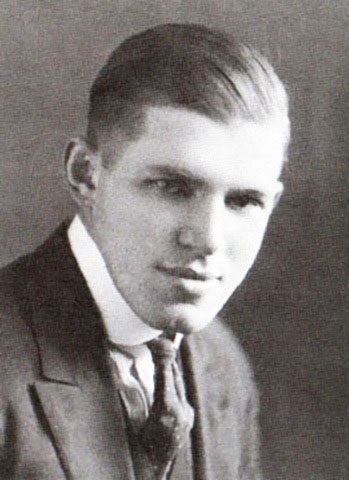

John A. Larson in 1921. (Photo: Wikimedia).

For a long time, many believed that lying caused physical side effects, and a man thought he had discovered the scientific mechanism for detecting lies in the 1920s, during a crime wave. This was a time when Prohibition was in effect in the United States, and smuggling gangs were rampant.

Some police departments adopted increasingly aggressive measures to compel suspects to confess, such as beatings, cigarette burns, and sleep deprivation. Despite being illegal, these methods were widespread in the U.S. and yielded many confessions, though many of those confessions were doubted in terms of their accuracy.

August Vollmer, the police chief of the Berkeley Police Department in California, believed a new era could be opened where science would make the interrogation process more accurate and humane. He began recruiting college graduates to help professionalize the police force. This aligned with John A. Larson, who had just earned a PhD in physiology from the University of California, Berkeley, and had a passion for justice. Larson joined the Berkeley police force in 1920, becoming the first rookie in the area with a doctorate.

Vollmer and Larson were particularly interested in a simple lie detection test created by William Marston, a lawyer and psychologist. Larson endeavored to create a much more complex test. He experimented in the university laboratory with a bizarre combination of pumps and gauges attached to the human body via wrist and chest straps.

Larson’s device would simultaneously measure changes in heart rate, respiration, and blood pressure during the continuous monitoring of an interrogated subject. He believed the device would detect false answers through specific fluctuations traced by a pen on a rotating paper roll. The operator would then analyze and interpret the results.

John A. Larson’s first lie detector. (Photo: Cade Martin).

In the spring of 1921, Larson unveiled the psychophysiological device, later known as the lie detector (polygraph). The machine resembled a combination of a radio, a stethoscope, a dental drill, a gas stove, and various other devices, all laid out on a long wooden table. The machine attracted significant attention, and the Examiner praised it: “All liars, no matter how clever, will meet their end.”

Larson himself was not entirely convinced by this hype. When testing his invention, he discovered alarming error rates and grew increasingly concerned about its official use. And although many police departments across the U.S. adopted the device, judges were even more skeptical than Larson.

In 1923, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Washington D.C. area ruled that the results of the lie detector could not be accepted in court because the tests were not widely accepted by relevant experts. However, the police continued to use the machine. Larson was even dismayed when a former colleague was granted a patent for an updated version in 1931.

While Larson’s original machine gathered dust, imitators developed many more modern versions, all adhering to similar parameters as Larson’s—and millions of people underwent testing. During the Cold War, the U.S. State Department used lie detectors to weed out suspected unsuitable individuals from the federal government. Many innocent employees lost their jobs, while others—who would later be revealed as adversaries, including the infamous spy Aldrich Ames—managed to fool the tests.

Larson obtained a medical degree and spent the rest of his life as a psychiatrist. However, he always mourned the lie detector, describing it as his “Frankenstein monster”, uncontrollable and indestructible.

In 1988, the U.S. Congress finally passed a law prohibiting private employers from requiring lie detector tests, although some government agencies still use it for screening, and police may use it with suspects as an investigative tool in certain cases.