The Jewish people experienced a long period of living under the domination of the Roman Empire until they revolted in 66 AD, forcing the Roman Emperor to send his most elite legions to Jerusalem.

In 64 AD, Gessius Florus became the Roman governor of Judea (now Israel). Known for his antagonistic views towards the local population, Florus showed little concern for the religious life of the Jewish people.

The siege of Jerusalem in 70 AD is considered the bloodiest tragedy in ancient history.

When tax revenues sharply declined, Florus ordered the confiscation of valuables from the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem. This led to a wave of outrage among the populace.

The Temple, dedicated to God, is the supreme deity in Jewish belief. The first Temple was built by King Solomon in 1000 BC and was later destroyed by the Babylonians. The second Temple was constructed in 516 BC and stood until the Roman attack on Jerusalem in 70 AD.

In 66 AD, the Roman army entered Jerusalem, killing 3,600 people. Florus’s actions sparked a Jewish revolt, known as the First Jewish-Roman War.

The Jewish Revolt

The revolt originated in Jerusalem. The citizens blocked tributes intended for Caesar from entering the Temple. Soon after, the entire city of Jerusalem became inflamed, expelling or killing Roman soldiers. The revolt spread throughout Judea.

In 67 AD, Cestius Gallus, the governor of the nearby province of Syria, brought 20,000 troops to Judea to quell the uprising. After a six-month siege of Jerusalem, Gallus was unsuccessful. 6,000 Roman soldiers died, including 5,300 infantry and 380 cavalry. The weapons of the Roman army were recovered by the Jews for use in later defenses.

Nero, the fifth emperor of Rome, sent Vespasian, a skilled and influential general at the time, to Judea to suppress the revolt.

Vespasian crushed the Jewish uprising in Galilee (now northern Israel) and surrounding areas. The Roman army under Vespasian besieged Jerusalem.

A representation of part of the wall of Jerusalem.

However, before breaching the city, Vespasian received alarming news from Rome. Emperor Nero suddenly died, and Vespasian found himself in a power struggle as various Roman armies in the eastern provinces regarded him as emperor.

Vespasian was declared emperor in 70 AD and returned to Rome. He entrusted his son Titus with the continuation of the conquest of Judea.

After four years of fighting for autonomy from the Romans, the Jewish community in Jerusalem failed to establish a clear strategic direction and even experienced internal conflicts, leading to a poorly disciplined army unprepared for future battles.

The Bloodiest Siege in Ancient History

Titus brought 70,000 Roman troops, including four elite legions, and began the siege of Jerusalem on April 14, 70 AD. This coincided with a time when many Jews were traveling from afar to participate in the Passover.

At the time of the siege, Jerusalem was defended by nearly 40,000 well-equipped soldiers. The city walls were extremely formidable, divided into three layers, with the final outer layer protecting the Temple.

Titus employed classic siege tactics of the time, blocking all supply routes from the outside.

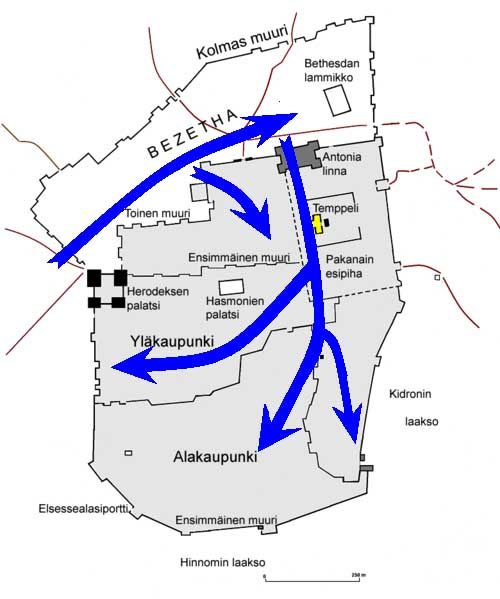

According to the famous Jewish historian Josephus (37-100 AD), Titus was very careful in strategizing the siege. The Roman legions assembled along the northern and western walls, with soldiers arranged in seven rows, cavalry in three rows behind, and archers in the middle.

After about a month, waiting for the inhabitants of the city to fall into hunger, Titus began his offensive. He introduced a type of siege weapon the Jews had never seen before—a specialized chariot designed to break down walls.

At three different points, the siege chariots simultaneously attacked. The Jews bravely fought during the day and tried to reinforce the increasingly weakened walls at night.

The path of the Roman attack on Jerusalem in 70 AD.

Eventually, the first wall fell, and Titus and his elite troops rushed in.

“The Jews were forced to retreat to the defenses behind the second wall. Titus continued to order the assault. For five days, the fighting became more intense than ever. The Jews fought as if they were prepared to sacrifice themselves to defeat their enemies,” Josephus recorded.

The second assault was easier; Titus only took five days to force the Jewish forces to retreat from the second wall.

Titus initially ordered his Roman soldiers not to burn houses or massacre civilians. However, the hawkish faction of the Jews still wanted to fight, seeking to ambush the Romans from all sides.

After the next three days, the Jews were pushed back to their final defense line, protecting the Temple. Titus did not rush, allowing his soldiers to rest, check their armor, and ensure they were fully paid.

“The situation was dire, famine was widespread. Many people resorted to eating their own kind to survive. Those who sneaked out to find food were captured by Roman soldiers, tortured, and crucified,” Josephus wrote.

During this bloody siege, Josephus was sent by Titus as a negotiator, but the Jews resolutely refused to surrender.

The battle turned into a massacre of the Jews.

After multiple attempts to breach the third wall failed, Titus shifted to nighttime ambush tactics. Fighting along a section of the wall continued from night into day, but the Romans managed to control part of the wall, gradually pushing back the Jewish defense.

Losing control of the third wall, all defensive efforts collapsed. Josephus recorded that Titus wanted to preserve the Temple, but the soldiers, furious over the stubbornness of the opponents, set the Temple ablaze. By September 8, 70 AD, Jerusalem officially fell under Roman control.

Josephus recorded that over 1.1 million people perished in the bloodiest siege in ancient history. The Jewish historian explained the unusually high death toll as being due to the inclusion of pilgrims who had come to Jerusalem for Passover. A large number of these pilgrims were trapped in the city and lost their lives.

The rebels, the elderly, and the weak were all slaughtered by Roman soldiers, with only 97,000 people being taken as slaves.

American historian Seth Schwartz remarked in 1984 that Josephus may have exaggerated the death toll, and his accounts showed some bias towards the Roman Empire.

After the fall of Jerusalem, Josephus accompanied the Romans back to Rome, becoming a Roman citizen. He spent the rest of his life documenting the history of the Jewish people.