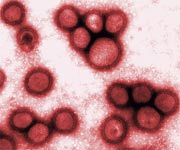

For the first time in human medical history, scientists will reconstruct the Spanish flu virus – the “death virus” of 1918 that claimed millions of lives worldwide. This is not a science fiction story.

For the first time in human medical history, scientists will reconstruct the Spanish flu virus – the “death virus” of 1918 that claimed millions of lives worldwide. This is not a science fiction story.

The goal of this exciting project is to equip scientists with better knowledge to combat future global pandemics, starting from the current spread of avian influenza in Southeast Asia. The research team believes their work will provide evidence that the 1918 flu pandemic originated from birds and offer a closer look at how it attacked and thrived within the human body. Above all, this project marks a historic milestone, as it involves the re-creation of a pathogen that caused a devastating pandemic in human history.

Scientists assure that the re-emergence of the 1918 “death virus” does not pose a threat to the community. Approximately 10 vials of the virus will be carefully stored at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, as stated by Terrence Tumpey, a member of the research team.

Similar to the 1918 virus, the current H5N1 avian flu strain in Southeast Asia also originates from birds. In 1918, a mutated flu virus infected humans and subsequently spread from person to person. Meanwhile, the H5N1 virus in Asia has already infected people, resulting in at least 65 deaths, but it has not yet shown signs of human-to-human transmission. However, the world of viruses is notorious for its rapid mutation capabilities, which means that H5N1 could soon develop infectious characteristics similar to the earlier 1918 virus. Therefore, “the need to understand what happened in 1918 is urgent,” said Dr. Jeffery Taubenberger from the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, who leads the gene sequencing project for this study.

The Spanish flu pandemic in 1918 spread globally within a few months, resulting in an estimated 20-50 million deaths. In severe cases, victims suffered from pleural effusion during the illness, which lasted less than a week. This strain of influenza was particularly dangerous for young people, a demographic that typically faces fewer complications compared to the elderly. Some experts suggest that one reason the outbreak was exacerbated was the malnutrition and poor living conditions at the end of World War I.

One reason the research team believes the re-creation of the 1918 virus does not threaten the community is that modern pharmaceuticals can effectively treat the 1918 flu. Furthermore, humans today have partial immunity to the disease. This is because the subtype of the 1918 virus is quite common today, making it familiar to the human immune system, according to microbiologist Adolfo Garcia-Sastre from Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York.

In a study published in the journals Sciences and Nature, scientists explained how they are recreating the 1918 virus: By using the remains of a woman who died from the flu and was buried in frozen ground in Alaska in 1918, they constructed a genetic sequence of the virus. They shared this with Dr. Garcia-Sastre and his colleagues at Mount Sinai, who will use this code to create a virus-like gene sequence known as a plasmid. These plasmids are then sent to the CDC, where they are implanted into human kidney cells – the final step in the reconstruction process. “Once the plasmid is introduced into human kidney cells, the virus will self-assemble,” Tumpey explained, “this only takes a few days.”

A typical flu virus consists of 8 gene segments. Taubenberger