Scientists at RIKEN in Japan have developed a radiation therapy technique for various types of cancer by generating alpha radiation within cancer cells to destroy them without harming healthy tissues.

The research team, led by Professor Katsunori Tanaka at the RIKEN Cluster for Pioneering Research (CPR) and Hiromitsu Haba at the RIKEN Nishina Center for Accelerator-Based Science (RNC), has created a new technique that can broadly treat several types of cancer with fewer negative side effects compared to current methods.

Cancer treatment using radiation therapy within cells. (Illustrative image from SciTech Daily)

SciTech Daily reported a scientific paper published on June 27 in the journal Chemical Science, indicating that the tumors in mice shrank nearly threefold, and the survival rate was 100% after a single injection of the compound. This compound is designed to emit a small amount of alpha radiation from inside the cancer cells, effectively killing cancer cells while leaving healthy tissues unharmed.

The side effects of standard chemotherapy and radiation therapy can severely impact patients’ health, and the ability to eliminate all cancer cells in the body is not guaranteed, especially when cancer has metastasized and spread throughout the body.

Thus, the goal of most current research is to find methods that specifically target cancer cells so that treatments only affect tumors. Some targeted therapies are currently being applied, but they are not suitable for all types of cancer.

Professor Tanaka stated: “One of the greatest advantages of our new method is that it can be used to treat many types of cancer without the need for any specific targeting vectors like antibodies or peptides.”

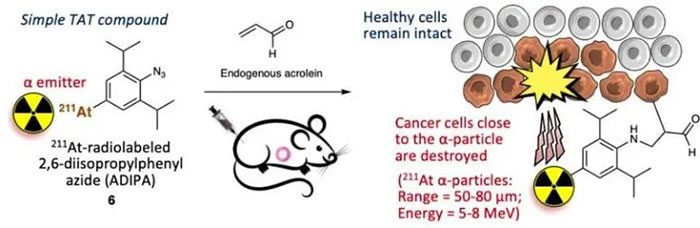

Diagram of using 2,6-diisopropylphenyl azide (ADIPA) labeled with radioactive 211At for targeted alpha therapy (TAT). (Image: RIKEN).

The new technique is based on fundamental chemistry, leveraging the tendency of cancer cells to accumulate a compound called acrolein and introducing a radioactive isotope, astatine-211, into the cancer cells, which emits alpha radiation during its decay.

Several years ago, Professor Tanaka’s team used a similar technique to detect individual breast cancer cells. The scientists attached a fluorescent compound to a specific azide (a high-energy molecule), which is an organic molecule with a group of three nitrogen atoms (N3) at the end.

When azide and acrolein meet in cancer cells, they react, and the fluorescent compound becomes anchored to the structures inside the cancer cells. Since acrolein is virtually absent in healthy cells, this technique functions like a probe, causing cancer cells to glow within the body.

In the new study, instead of merely detecting cancer cells, the research team aimed to destroy those cells. The logic is simple: instead of attaching azide to a fluorescent compound, the researchers attached an organic compound to a radioactive substance that can kill cells without harming surrounding cells.

The research team chose astatine-211, a radioactive isotope that emits a small amount of radiation in the form of alpha particles over a period of more than 8 hours during its decay. Compared to other radiation therapy methods, alpha particles are somewhat more dangerous, but they can only travel about 1/20 mm and can be blocked by a piece of paper. Theoretically, when astatine-211 anchors inside cancer cells, the emitted alpha particles will destroy the cancer cells.

After determining the best way to attach astatine-211 to the azide probe, the research team conducted experiments to demonstrate their concept and test their theory.

The team implanted human lung tumor cells into mice and conducted treatment experiments under three conditions: injecting astatine-211 directly into the tumor, injecting the astatine-211-azide probe into the tumor, and injecting the astatine-211-azide probe into the bloodstream.

The scientists found that without targeting, the tumors continued to grow, and the mice could not survive. As expected, when the azide probe was used, the tumors grew nearly three times slower, with many experimental mice surviving—100% when injected into the tumor and 80% when injected into the bloodstream.

Mr. Tanaka emphasized: “We discovered that just one injection of 70 kBq of the radioactive compound into the tumor was extremely effective in targeted cancer treatment and in destroying tumor cells. Even when the treatment compound was injected into the bloodstream, we could still achieve similar results. This means that we can use the blood injection method to treat cancer at very early stages even if we are not sure where the tumor is located.”

A fluorescent probe version of this technique has been tested in clinical trials as a method for detecting and diagnosing cancer at the cellular level. The next research phase is to find partners and begin clinical trials using the new method to treat cancer in humans.