The North American power grid consists of 5 smaller grids, considered the largest machine ever created by humanity.

The United States alone owns 965,606 kilometers of transmission lines and 8.8 million kilometers of distribution lines. In every regard, this is a remarkable engineering achievement, according to Popular Science. This machine has evolved from a small power station in New York City to a massive project spanning the entire continent.

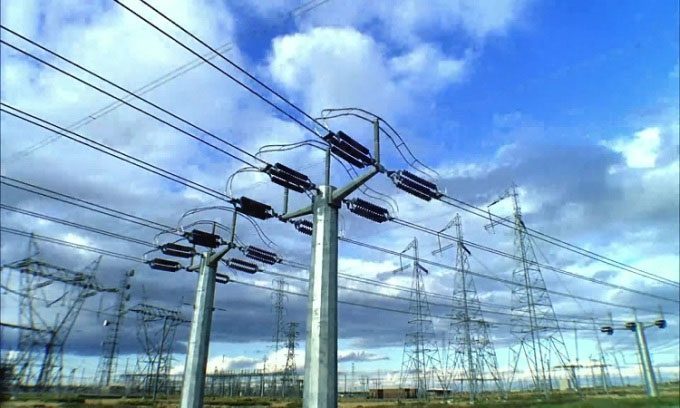

Electric transmission lines in the U.S. (Photo: Popular Science)

At 3 PM on September 4, 1882, an engineer working at a power station in downtown Manhattan switched on a circuit breaker. Within seconds, six 100-kilowatt direct current (DC) generators, each weighing 27 tons and powered by coal, began operating. Providing direct current (DC) to residents within a 400-meter radius, Thomas Edison’s Pearl Street Station was the first power station in the world to illuminate 400 lamps for its initial 85 customers. This marked the beginning of the power grid in the United States.

Although the Pearl Street Station ushered in a new era and Edison’s DC technology proved its value, it could not transmit over long distances since engineers of the time could not increase the voltage after generating power. Due to this limitation, power stations needed to be built as frequently as post offices in cities and towns.

However, with the support of entrepreneur George Westinghouse, another inventor and former Edison employee named Nikola Tesla developed an induction motor using alternating current (AC), which was easier to produce and lost less energy because its voltage could be increased or decreased using transformers.

The competition between the two parties lasted until the late 1880s, with AC gradually pulling ahead. By the 1890s, several AC power stations in Colorado, Oregon, and California began transmitting electricity over long distances to residents. As the Battle of Currents neared its conclusion, many power plants sprang up across the United States, supplying electricity to new inventions like electric trolleys.

The visionary leading the U.S. power grid into the future was entrepreneur Samuel Insull. When Insull arrived in Chicago in 1892, the city sourced electricity from 20 different companies. After becoming president of the Chicago Edison Company, Insull quickly increased the load factor, utilizing steam turbines more efficiently, and acquired other companies to convert rival power plants into substations. Within 15 years, Insull had acquired over a dozen power generation facilities and rebranded the company as Commonwealth Edison.

Many businessmen quickly imitated Insull’s success, raising concerns about monopolies. The U.S. government established several regulatory agencies at both local and federal levels. America became increasingly electrified, with President Franklin Roosevelt passing numerous policies to encourage competition while extending electricity to rural areas.

Ultimately, before World War II, the modern U.S. power grid began to take shape. To prevent power outages, the federal government mandated interconnections between electric companies. This meant that if there was a blackout in Boston, Massachusetts, electricity generated in Ohio could compensate for the shortfall. By the 1960s, the Eastern and Western power grids supplied most of the electricity in the U.S. Although these two major grids were synchronized, the connections between them were very limited.

Throughout the 20th century, advancements in high and low voltage direct current (DC) technology emerged. In 1990, the first large high-voltage direct current (HVDC) system began supplying electricity to New England. The HVDC system is more expensive due to requiring converters at both generating stations and substations, but it can transmit electricity further and more efficiently than high-voltage alternating current (HVAC) systems. Today, HVDC is preferred when electricity needs to be transmitted over distances of nearly 650 kilometers.