Thanks to the use of a new method, scientists have successfully extracted and identified the owner of an ancient DNA sample found on a Stone Age pendant made from the tusk of a moose.

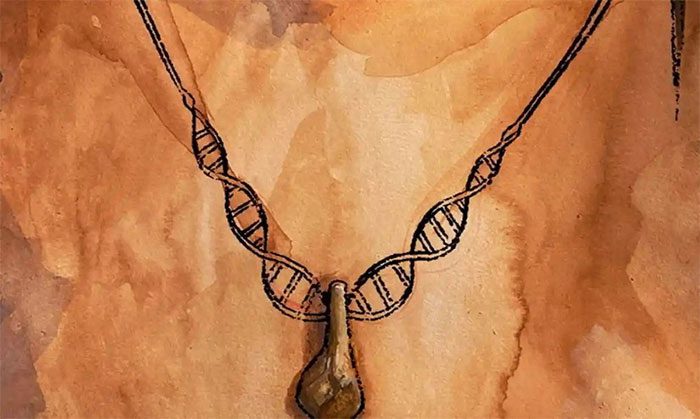

Illustration of the pendant, discovered at Denisova Cave in southern Siberia, Russia. (Photo: Reuters).

According to a paper published in the scientific journal Nature on May 3, researchers found this 19,000 to 25,000-year-old pendant in Denisova Cave in the Altai region of Russia. The creator of this pendant drilled a hole in the tusk to allow for a cord to be threaded through. The tusk may also have been part of other jewelry items such as headbands or bracelets.

This cave is an important archaeological site as it has long been inhabited by extinct human species, including the Denisovans and Neanderthals. Additionally, it has also been home to modern humans – Homo sapiens at different points in time. Over the years, Denisova Cave has yielded many significant archaeological discoveries, including the earliest artifacts recovered from Denisovans, along with various tools and other artifacts.

The discovery of objects that were once used as tools or personal jewelry, such as this pendant, plays a crucial role in helping scientists understand human behavior in the past.

According to Guardian, quoting molecular biologist Elena Essel from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany – the lead author of this study, “Objects created from the distant past are extremely fascinating because they allow us to open a small window to travel back and see through the lives of these people.”

Essel shared that when holding such an artifact, she feels like “traveling back in time, imagining the hand of the person who created and used it thousands of years ago.” When looking at this unique pendant, she noted that a multitude of questions arose in her mind.

“Who made it? Was this tool passed down from one generation to another, from mother to daughter or from father to son? The fact that we can begin to address these questions using genetic tools is still completely unbelievable to me,” Essel said.

Image of the necklace made from moose tusk. (Photo: Nature).

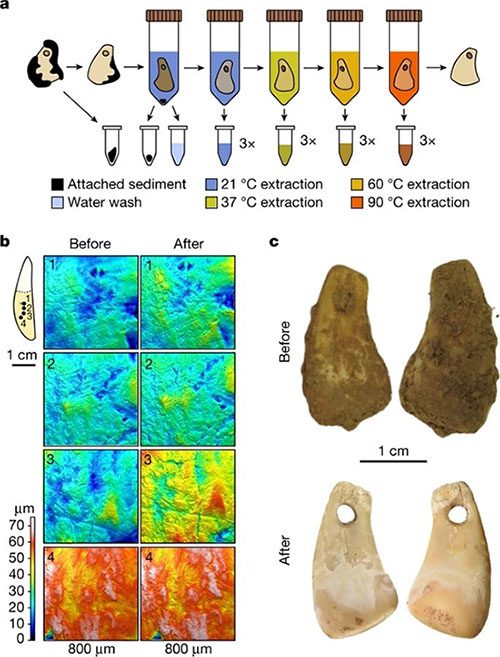

To find answers to these questions, the researchers, led by Essel, used gloves and masks while excavating and handling the pendant to avoid contaminating it with modern human DNA.

They then employed a non-destructive method to isolate DNA present in skin cells, sweat, or other bodily fluids absorbed by certain porous materials such as bone, tooth, and ivory. Essentially, this method works similarly to a washing machine, as the pendant is soaked in a liquid that releases DNA from it, just as a washing machine removes stains from clothing.

The results showed that the DNA on this necklace belongs to a Stone Age woman who is closely related to a group of hunter-gatherers known to have lived in a part of Siberia, east of Denisova Cave.

This also makes the pendant the first prehistoric artifact genetically linked to a specific individual. However, this study cannot determine whether this woman created the pendant or simply used it.

Nevertheless, commenting on this research, Marie Soressi, a senior archaeologist at Leiden University, stated that it has “opened up tremendous opportunities to better reconstruct the roles of individuals in the past according to their gender and ancestry.”

By linking objects to specific individuals, this technique can shed light on prehistoric social roles and the division of labor between genders, or clarify whether an object was created by our species.