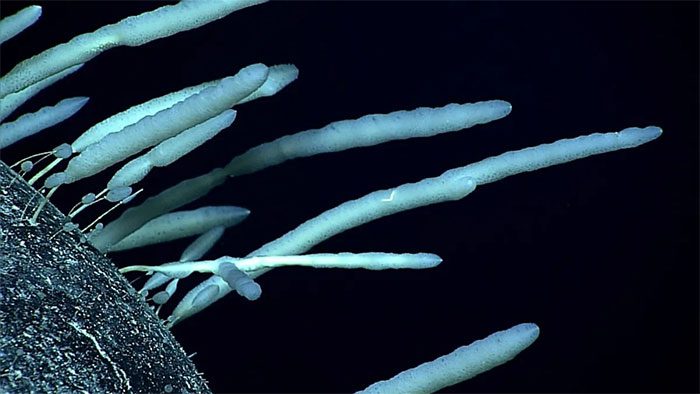

One of the most astonishing examples is the sponge species Monorhaphis chuni found in Antarctica, with a specimen estimated to have existed for over 11,000 years.

Monorhaphis chuni spends its entire life firmly attached to the ocean floor thanks to a single giant silicon spine. This spine, which acts as its backbone, not only anchors the sponge’s body but also forms a continuous cylindrical structure.

Not only its unique structure but the longevity of M. chuni also amazes scientists. In 2012, a research team analyzed a specimen over 2 meters long and discovered that its silicon glass fiber structure grows similarly to tree rings, preserving important information about climatic history.

When it comes to sponges, few people realize that these stationary, plant-like creatures are actually animals. However, sponges are not only animals; they are among the longest-living species on the planet.

11,000-Year-Old Sponge and Its Treasure Trove of Climate Information

The M. chuni specimen was discovered in the East China Sea in 1986, at a depth of 1,100 meters. Analysis results show that this sponge has witnessed over a millennium of climate fluctuations. Through the growth rings on its silicon spine, scientists found signs of various phases of water temperature changes.

Klaus Peter Jochum, the lead author of the study, shared: “Under the electron microscope, we found four uneven growth areas, indicating rising water temperatures during periods of underwater volcanic eruptions.” These changes included temperature increases from below 2°C (35.6°F) to 6–10°C (42.8–50°F) during significant upheavals.

With its remarkable lifespan, sponges like M. chuni are not only living witnesses to Earth’s history but also a valuable repository of climate information. By studying these specimens, we can gain deeper insight into temperature and deep ocean environmental changes over thousands of years—a task that was once merely speculative.

Beneath their simple exterior, sponges like Monorhaphis chuni truly harbor many wonders. The silicon spines are not just survival tools but also an “archive” documenting Earth’s history, helping humanity decode secrets about ancient environments and climates.