-

Construction Period: 1840 – 1860

-

Location: London, England

The Palace of Westminster (UK) is a world-renowned structure, most notably recognized for its sprawling façade along the River Thames, with rich vertical Gothic details and three contrasting towers – the massive square Victoria Tower at the southern end, the octagonal spiral of the Central Tower, and at the northern end, the slender Clock Tower adorned with a steeply pitched roof, beautifully decorated above the bell tower, which houses the great bell – Big Ben, often associated with the Parliament in the public’s imagination. However, the 19th-century features and current use disguise its previous palace origins, which boast nearly a thousand years of history and several magnificent medieval relics. This explains why the name Westminster Palace is often used to refer to the Palace of Westminster (UK).

View of the Palace of Westminster from above to the Northeast

showing the sprawling riverside façade.

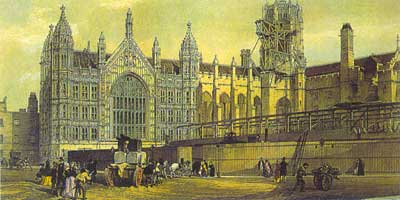

The Old Westminster Palace.

To understand the foundations of the Palace, we must go back to the time of Edward the Confessor, who began construction in the late 1040s on the land later known as Thorney Island, a low-lying area with many marshes dug from the riverbank ditches. There, he also rebuilt the grand St Peter’s Abbey, and the history of the Palace and the abbey have been closely linked until the 16th century.

|

| A view of Westminster Hall towards St Stephen’s Gate with 11th-century walls and a 14th-century roof. |

The palace remained the main residence of the Kings of Norway, and the magnificent Hall still exists, added by William II between 1097 and 1099, which at that time was likely the largest palace in Europe and undoubtedly a marvel in itself. From 1292, a new royal chapel was constructed to honor St Stephen, with the crypt completed in 1297 and the chapel above finished in 1348, by which time a community of clergy had been established. The chapel was richly decorated, but only the crypt remains along with many fragments of the chapel above.

From 1397 to 1399, the final marvel of the medieval period was added, the charming hammer-beam roof of Westminster Hall, significantly expanding the width of the hall without requiring additional support, a structure that has remained essentially unchanged to this day. It has yet to be definitively proven how the roof, estimated to weigh 660 tons, was supported. The final hypothesis suggests that the roof was supported directly by the walls rather than by a load-bearing framework of the vault.

Immediately following the suppression of religious communities in 1547, including St Stephen’s community, Parliament frequently utilized vacant buildings locally – the House of Commons used the upper part of St Stephen’s chapel, while the House of Lords used a larger room further south in the former apartments of medieval queens. It is believed that the seating in the House of Commons, where members faced each other with the main aisle down the center, was later mimicked by the House of Lords, originating from the community structure. This arrangement was unsuitable and inconvenient, but proposals for new Neoclassical buildings were unsuccessful. From the early 19th century, numerous changes and additions were made, but the core of the old buildings, deemed sacred by tradition, remained until the fire in October 1834 completely destroyed them.

The New Palace of Westminster.

Fact Sheet:

-

Riverside façade length: 286.5m

-

Clock Tower height: 94.5m

-

Victoria Tower height: 102.5m

-

House of Lords inaugurated: April 1847

-

House of Commons inaugurated: February 1852

-

Bombed in May 1941, reopened in October 1950.

View across the Palace courtyard towards St Stephen’s Gate

with the Western façade in close-up and the Central Tower

at the foundation still under construction, lithograph circa 1852.

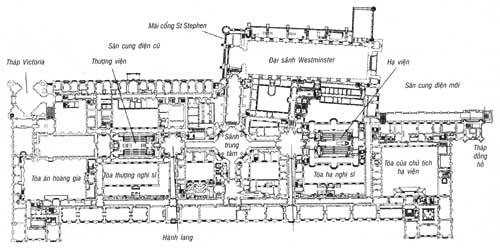

It was necessary to decide to completely rebuild, selecting an architect through a competition that stipulated either Gothic or Elizabethan Renaissance style. While the artistic details of the building had to draw from earlier periods to harmonize with the surroundings, especially Westminster Hall and Westminster Abbey, a modern legislative body required updated access conditions. In January 1836, Charles Barry was chosen due to his tightly arranged plan, which allowed for effective movement of various user groups: the king, members of the bicameral legislature, officials, and the public. The design

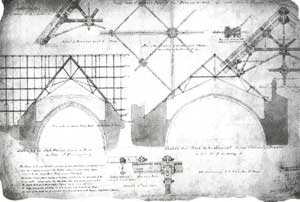

|

| Construction drawing showing the structure of the iron framework supporting the roof of St Stephen’s Hall. |

featured a unified main floor where all main rooms were arranged, with both houses located along the central longitudinal axis, facing each other, with a corridor and a central octagonal hall in between. The entrance, regrettably now lost, was designed by A.W. Pugin, who was skilled in drafting and knowledgeable about Gothic details, likely influencing those who were well-versed in the style.

The new building site occupies approximately 3.25 hectares; much of the increase is due to the construction of embankments. The first task was to build a quay wall behind the embankment, which took 16 months to complete using traditional methods, which were also applied to excavate the river walls and the terraced area. The riverside wall was built with granite and extended below the Trinity tidal peak of 7.6m. Granite also lined the concrete foundation, behind the stone, and the eastern wall of the main building, with space also filled with concrete. At that time, a large concrete raft foundation was formed for the entire superstructure. The extensive use of concrete was a relatively new development and had been applied for foundation work in the British Museum a few years earlier.

The brick foundation features two intersecting curved arches with stone filling, along with iron, cast iron, and wrought iron; wood was only used for connecting parts. Haunted by the recent fire, there was a strong focus on constructing as fireproof as possible.

Main Floor Plan of the Palace of Westminster (UK)

The flooring typically features shallow brick arches between inverted T girder beams, but the flooring in both houses had to be entirely of cast iron (each beam was “certified” right on site). More significantly, the roofs throughout the building all had interlocking iron trusses. The three main towers of the Palace also exemplify typical structural techniques, showcasing a wealth of skills displayed in construction. The expansive and ornately decorated lower level of the Victoria Tower is designed as the king’s entrance, and the nine floors above have been used for parliamentary record storage, thus also constructed to be fireproof. Both the Victoria Tower and the Clock Tower are built on thick poured concrete foundations, with stone-clad brick walls, constructed without external scaffolding.

|

|

|

Top of the Clock Tower

Leave a Reply |