To create the first image of a black hole captured four years ago, researchers utilized a network of radio telescopes to gather data about the swirling light and gas.

The researchers employed artificial intelligence (AI) technology to recreate the first image of a black hole taken four years ago.

This AI-generated image of the black hole was published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters on April 13.

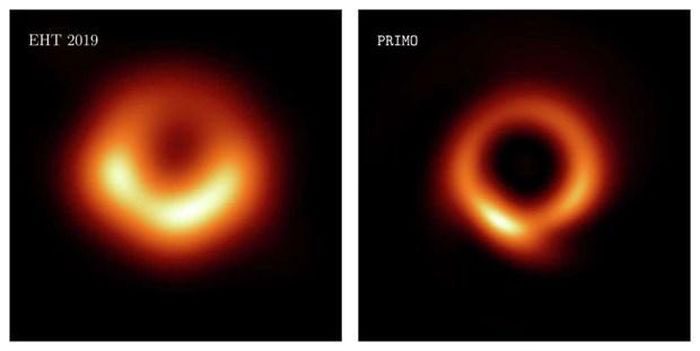

In 2019, the first image of a black hole was unveiled, revealing a hazy object shaped like a doughnut (a type of ring-shaped pastry) engulfed in flames. This image depicts the supermassive black hole at the center of the Messier 87 galaxy (M87), located 53 million light-years from Earth.

The black hole image published in 2019 (left) and the 2023 image. (Source: AP).

To produce that image, researchers used a network of radio telescopes to collect data on the light and swirling gas. However, there were still many gaps in this data.

In the new study, scientists utilized available data along with machine learning technology to fill in the missing parts. The newly created image resembles the original, but the doughnut ring is thinner and the central part is darker.

Dr. Lia Medeiros, an astrophysicist at the Institute for Advanced Study in New Jersey (USA) and the lead researcher, shared: “I feel like this is truly the first time I’ve seen that image.”

Building on the success of the image, the research team hopes to further study the characteristics and gravitational forces of black holes in the future.

Dr. Medeiros also mentioned that the team plans to use machine learning to generate more images of other celestial objects, potentially including the black hole at the center of the Milky Way.

According to a study published on March 28 in the journal of the Royal Astronomical Society, British astronomers have discovered one of the largest black holes to date using a new technique, opening up hopes for the discovery of thousands of other black holes beyond the universe in the near future.

The newly discovered black hole has a mass 30 billion times that of the Sun and is located about 2 billion light-years from Earth.

This is one of the four largest black holes ever observed and is the first black hole observed using gravitational lensing, where light from a distant galaxy is amplified and directed inward, representing an image of a massive black hole.

The lead author of the study, astronomer Dr. James Nightingale from Durham University (UK), described this process as “similar to shining light through the bottom of a wine glass,” which will allow astronomers to explore black holes in 99% of other galaxies that are currently inaccessible.

In this latest discovery, researchers also utilized computer simulations and images from the Hubble Space Telescope to confirm their findings and eliminate potential factors that could lead to inaccuracies, such as excessive concentration of dark matter.

Dr. Nightingale believes that the enormous size mentioned is consistent with estimates for a black hole at the center of the host galaxy.

This could also be the largest black hole ever recorded, but it is difficult to assert this definitively due to differences in detection techniques and uncertainties involved.

According to researcher Nightingale, the cosmic landscape is also about to undergo significant changes.

The European Space Agency is expected to launch the Euclid space telescope mission in July 2023, which is anticipated to usher in a “big data era” by creating a massive, high-resolution map of the universe.

Dr. Nightingale hopes that in the next six years, Euclid could help uncover thousands of hidden black holes.

Previously, on February 22, NASA announced that through the Chandra X-ray Observatory, they had discovered two massive black holes in a dwarf galaxy about to collide.

NASA emphasized that this collision could provide scientists with crucial information about the development of black holes in the early universe.

NASA stated that, by definition, dwarf galaxies contain stars with a total mass less than about 3 billion times that of the Sun.

Astronomers have long theorized that dwarf galaxies merged relatively early, especially in the early universe, to evolve into the larger galaxies we see today.

However, current technology cannot observe early dwarf galaxy mergers because images from such vast distances are very faint.