Marie Curie (1867 – 1934) was one of the pioneering scientists in the study of radioactivity. Her accomplishments were immense, influencing future atomic physicists and earning her two prestigious Nobel Prizes. The discovery of the neutron by Sir James Chadwick and the artificial radioactivity by Irène and Frédéric Joliot-Curie both stemmed from Marie Curie’s research.

1. Early Years.

|

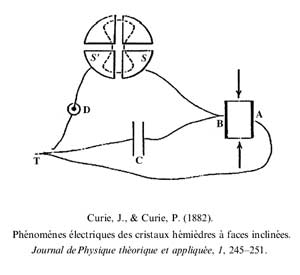

Quartz Crystal |

On November 7, 1867, in Kraków, a small town near Warsaw, Poland, professor Wladislaw Sklodowski and his wife welcomed their youngest daughter, Marya Sklodowski. From the moment she was born, the Sklodowski family faced misfortune, and her mother suffered from a terminal illness: tuberculosis. Consequently, despite her love for her children, Mrs. Sklodowski never dared to embrace them. Lacking maternal affection, little Marya often clung to her older sister, Zosia, to listen to fairy tales. Additionally, Marya enjoyed gazing at her father’s science cabinet, filled with various items: test tubes, barometers, scales, and geological specimens.

Marya’s family life was not cheerful, and the national situation was even more dismal. Around 1872, when Marya was five years old, Poland was torn apart by three empires: Russia, Germany, and Austria. Her homeland fell under the influence of the Tsar. After the failed people’s revolution in 1831, King Nicholas of Poland, under the direction of Russia, severely suppressed patriotic revolutionary elements: imprisoning, exiling, and confiscating property. Moreover, the regime implemented a very inhumane educational policy: the policy of ignorance. At that time, science and philosophy were beginning to develop vigorously in Europe, yet the ideas of Auguste Comte, Darwin, and the inventions of Pasteur and Faraday could not penetrate Poland.

In this context, young Marya began her schooling. At first glance, she did not appear particularly intelligent; with her slightly elongated face and dreamy brown eyes, she seemed somewhat dull. However, young Marya was known for her academic excellence from an early age. Always two to three years younger than her classmates, she consistently topped her class in all subjects: from core subjects like mathematics, history, and literature, to secondary subjects including French, German, and even the Bible.

When Marya turned 10, her beloved sister and confidante, Zosia, tragically passed away from a contagious disease brought by her classmates: lice. Shortly thereafter, her mother, after years of suffering from tuberculosis, departed this world, leaving her father to care for four young children: one son, Joseph, and three daughters, Hela, Bronia, and Marya, all of school age.

In 1883, at the age of 16, Marya completed her secondary education and graduated with commendation from the examination board. At that time, her brother Joseph was studying at the Medical University, and her sister Bronia had also finished secondary school and aspired to become a doctor. However, at that time, medical schools did not accept female students, prompting her to seek a teaching position instead.

|

Piezoelectricity |

In 1884, Bronia moved to France to study at the University of Paris. Bronia chose France partly because the Sorbonne University was home to many renowned professors and partly because France was a free country, a desire shared by students worldwide at that time as well as in all eras. In France, diverse opinions were welcomed, which was essential for any progressive work in science and art. While Bronia was studying to become a veterinarian in Paris, Marya secured a teaching position in a remote rural area in Poland.

2. Period of Study Abroad.

Teaching was not a profession Marya enjoyed. After six long years of this monotonous life, in 1891, Marya decided to write to Bronia, asking for her assistance to study in France. On the day of her departure, Marya hesitated and told her father: “Father, I won’t be gone long, just two or three years to study, and then I will return to live with you forever.” But Marya could not keep this heartfelt promise. A scientist, a husband, and a soulmate kept her in France, and that person was Pierre Curie.

While living in France, to make her name easier to pronounce, Marya “translated” her name into French as Marie: Marie Sklodowski. Marie did not pursue medicine, dentistry, or pharmacy—fields favored by women at that time. For reasons unknown, she chose pure science. Initially facing difficulties with the language, Marie received guidance from a talented young professor, Paul Appell. Additionally, she learned from Professors Gabriel Lippmann and Edmond Bouty. She also met renowned physicists of the time, including Jean Perrin, Charles Maurain, and Aimé Cotton.

The life of a student abroad was quite challenging, with a significant barrier to her studies: financial issues—money for food, tuition, supplies, and transportation for her daily commutes to school. Winter in Paris was bitterly cold, yet this brave Marie immersed herself in her studies, and her efforts were rewarded: after three years of study, she graduated at the top of her class, receiving a Bachelor of Science degree in 1893, and the following year, she ranked second in the Mathematics degree examination. Upon completing her studies, she intended to return home, but feeling that her knowledge was still purely theoretical, Marie wanted to serve her country not just as a professor but as an engineer, aiming to assist her compatriots with more practical projects.

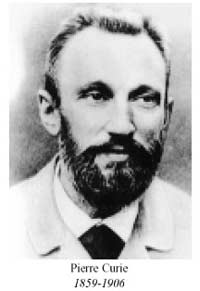

In 1893, through the introduction of Mrs. Dydynska, also a Pole, Marie applied for the Alexandrowitch scholarship to study iron and steel metallurgy. She was introduced to a young professor researching the magnetic properties of iron and steel: Professor Pierre Curie. Pierre Curie was born on April 19, 1859, in Paris, the second child of Dr. Eugène Curie. At the age of 16, Pierre passed his high school diploma, and at 18, he obtained his Bachelor of Science degree, then began working as a lecturer at the University of Paris in 1878. After graduating, Pierre Curie, along with his brother Jacques, immersed himself in experimental work: They researched the piezoelectricity of various crystals, particularly quartz.

In 1893, through the introduction of Mrs. Dydynska, also a Pole, Marie applied for the Alexandrowitch scholarship to study iron and steel metallurgy. She was introduced to a young professor researching the magnetic properties of iron and steel: Professor Pierre Curie. Pierre Curie was born on April 19, 1859, in Paris, the second child of Dr. Eugène Curie. At the age of 16, Pierre passed his high school diploma, and at 18, he obtained his Bachelor of Science degree, then began working as a lecturer at the University of Paris in 1878. After graduating, Pierre Curie, along with his brother Jacques, immersed himself in experimental work: They researched the piezoelectricity of various crystals, particularly quartz.

In 1883, Jacques was appointed as a professor at the University of Montpellier, and Pierre became a senior lecturer at the School of Physics and Chemistry. In 1895, Pierre Curie earned his Doctor of Science degree, and in the spring of 1894, while researching the electromagnetic properties of iron and steel, Pierre met Marie Sklodowski, who sought additional experience. Upon meeting the Bachelor of Science and Mathematics graduate from the Sorbonne, Pierre felt admiration and respect for this brilliant young woman. At that time, Pierre was 35 years old and still single, as he was engrossed in research. After several meetings and discussions with Marie about science, he immediately saw in her the image of his ideal wife. For Marie, after her first love in Poland ended, she wanted to erase love from her life. She found Pierre to be deserving, but still remembered her elderly father and her vow to study quickly to return and serve her homeland, so she left Paris. While bidding her farewell, Pierre pleaded, “You are talented. You should return to France to study science. You cannot abandon science.”

Marie Sklodowski was Poland’s first female engineer, but at that time, society did not have much faith in women’s talents, so she was not valued. Disheartened, having spent less than a year in her homeland, Marie decided to return to France; she could not abandon science or Pierre. Ten months later, Marie accepted Pierre’s marriage proposal. Their wedding was a simple affair on July 25, 1895: aside from close family members such as Dr. Eugène, Pierre’s father, Professor Sklodowski, Marie’s father, and her sister Bronia and brother Jacques, they only invited a few close friends. In their new family, only Pierre earned money, and his income was modest, while Marie still had not found a job; she was merely a brilliant student, an exceptional scientist. After two Bachelor’s degrees, Marie went on to earn a Master’s degree in Science and continued her research on the magnetic properties of iron and steel. In July 1897, Marie gave birth to her first daughter, whom they named Irène. From then on, the Curie family had new needs. Fortunately, Pierre secured a position for Marie as an assistant in his Physics laboratory, marking the beginning of the career of the world’s foremost female scientist.

3. Scientific Research.

Upon reading the research papers of physicist Henri Becquerel and after consulting with her husband, Marie Curie was determined to explore the still obscure realm of physics that few knew about. At that time, strange substances were known to emit rays, but no one understood how many such substances existed or how these substances and their rays differed. Physicists collectively referred to these substances as “radioactive materials.” After Wilhelm Röntgen discovered X-rays, Henri Becquerel speculated that radioactive rays shared the same origin as X-rays. He conducted numerous experiments on the radioactive rays of Uranium, similar to those he had performed with X-rays, and observed that both types of rays possessed similar properties. Becquerel pondered the reasons for radioactivity and where radioactive materials derived their energy, however minuscule, to emit light. Becquerel’s research was merely the beginning; a deeper understanding of the laws of radioactivity awaited the genius of Pierre and Marie Curie.

Upon reading the research papers of physicist Henri Becquerel and after consulting with her husband, Marie Curie was determined to explore the still obscure realm of physics that few knew about. At that time, strange substances were known to emit rays, but no one understood how many such substances existed or how these substances and their rays differed. Physicists collectively referred to these substances as “radioactive materials.” After Wilhelm Röntgen discovered X-rays, Henri Becquerel speculated that radioactive rays shared the same origin as X-rays. He conducted numerous experiments on the radioactive rays of Uranium, similar to those he had performed with X-rays, and observed that both types of rays possessed similar properties. Becquerel pondered the reasons for radioactivity and where radioactive materials derived their energy, however minuscule, to emit light. Becquerel’s research was merely the beginning; a deeper understanding of the laws of radioactivity awaited the genius of Pierre and Marie Curie.

After only a short period of study, Marie Curie discovered that not all of the Uranium ore was radioactive; rather, only a very small portion contained radioactive material. Although she understood that the concentration of radioactive material in Uranium was low, she was uncertain of the exact amount, estimating it to be about one part per thousand. In reality, later discoveries revealed that the concentration was even smaller: one part per million. However, the Curies’ contribution was significant as they informed the scientific community that many different radioactive materials existed, even if many were variants of one another, and that non-radioactive materials like lead and gold were also variants of radioactive substances. This understanding was crucial, as it ultimately led to the discovery of nuclear fission and the development of atomic bombs.

Initially, Marie Curie identified two different radioactive substances, the first discovered in the summer of 1891, which she named “Polonium” in honor of her beloved Poland, and the second substance, discovered a few months later, was called “Radium.” However, the Curies’ findings were not immediately accepted by the scientific community. Many skeptics refused to acknowledge the existence of Polonium and Radium, arguing that each substance must have specific physical and chemical properties. Questions arose about the atomic weight and molecular weight of Radium, its affinity for other substances, its salts, its color, and its fluidity. These inquiries left the young scientists overwhelmed. To appease the skeptical chemists, Pierre and Marie Curie needed to isolate pure Radium.

The material containing Radium is called pitchblende.

Pitchblende is a substance used in the glass-making industry. It is quite expensive, and the amount of Radium contained within it is limited. With their meager salaries, how could the two scientists continue their research? Fortunately, a Belgian glass manufacturer, having heard of the Curies’ reputation, agreed to transport a truckload of pitchblende, which was surplus to the factory’s needs, to France for them. Additionally, Pierre was able to secure an old building at the University of Science, where the couple set up their laboratory to process the pitchblende.

For four years, from 1898 to 1902, after processing 8 tons of pitchblende, the two scientists isolated 1 gram of pure Radium. This was the first gram of Radium ever discovered, valued at 750,000 gold francs, making Radium one of the most precious metals. Thus, Radium was officially “born” under the Curies’ discovery, with a molecular weight of 225.

For four years, from 1898 to 1902, after processing 8 tons of pitchblende, the two scientists isolated 1 gram of pure Radium. This was the first gram of Radium ever discovered, valued at 750,000 gold francs, making Radium one of the most precious metals. Thus, Radium was officially “born” under the Curies’ discovery, with a molecular weight of 225.

In 1898, the University of Sorbonne was in need of a Physics professor. Pierre applied, hoping for a better salary. However, since he had never attended a teacher’s college or a polytechnic school, his application was rejected. In 1900, Pierre Curie secured a professorship at the Polytechnic School with a salary of 2,500 francs per year. This income was still insufficient for the Curie family. Meanwhile, the University of Geneva, Switzerland, unexpectedly invited Pierre to become a Physics professor with an annual salary of 10,000 francs, along with two assistants and a fully-equipped research room. It was an unexpected stroke of luck. Unfortunately, Geneva was too far away, and the Belgian glass company refused to transport pitchblende there. Choosing between science and money, Pierre opted for science and graciously declined the offer from the University of Geneva.

Not long after, Pierre Curie was invited to teach Physics for the Natural Sciences diploma at the University of Sorbonne, while Marie was appointed as a professor at the École Normale Supérieure for female students in Sèvres. The family’s financial situation improved, allowing Pierre and Marie Curie to dedicate themselves to science.

In 1902, the results of the Radium discovery were published. Professor Mascart, appreciating Pierre Curie’s talent, encouraged him to apply to the Academy of Sciences, but on voting day, the Academy elected the opposing candidate, Amagat. At this time, Professor Paul Appell was appointed Dean of the University of Science in Paris. To comfort Pierre, Appell requested that the Minister of Education award him a medal of honor, and before presenting the medal, Appell urged Marie Curie to persuade her husband to accept it. However, Pierre refused, stating that he only needed a laboratory, not a medal to wear. Throughout his life, Pierre Curie longed to establish a research facility where anyone interested in studying radioactivity could freely access it.

After the discovery of Radium, the fame of the Curies spread beyond France. Since 1900, universities and research centers in countries such as England, Germany, Denmark, and the United States sent letters to the Curies inquiring about Radium. Physicists raced to understand radioactivity, including Boltzmann, Crookes, Paulsen, and Ramsay, who discovered many new substances like Mesothorium, Ionium, Protactinium, radioactive lead, and radioactive helium.

|

Marie Curie and her two daughters |

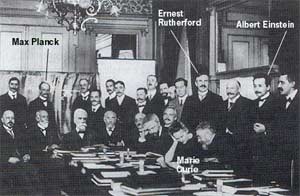

In 1903, Marie Curie was awarded a Doctorate in Science with high honors from the Sorbonne, commended by the examining board for her thesis “Research on Radioactive Substances.” That same year, the Royal Society of England invited the Curies to speak in England. Shortly thereafter, Sweden voted to award the 1903 Nobel Prize in Physics, dividing it into two halves: one for Henri Becquerel and the other for Pierre and Marie Curie for their work in discovering radioactive substances. The Curies received 10,000 gold francs. However, upon receiving the joyous news of the Nobel Prize, the scientists faced many inconveniences: curious onlookers and reporters surrounded their home, creating a noisy and chaotic environment that hindered their work. The Curies, who cherished tranquility for research, were understandably annoyed by the attention they received as if they were movie stars. Marie Curie remarked: “In science, we should focus on the objects rather than the personalities.”

After their talents were recognized abroad, Pierre Curie gained acknowledgment in France. In 1904, he was appointed as a full professor of Physics at the Sorbonne. Before accepting, he requested the establishment of a laboratory. This time, the Ministry of Education in France no longer indulged in frivolities like awarding medals; instead, they agreed to build a research center, allowing Marie Curie to head the Physics department under her husband’s direction, along with two assistant researchers. In 1904, the Curies also received another piece of good news: Marie gave birth to their second and youngest daughter, Eve Curie. In 1905, Pierre Curie was elected to the Academy of Sciences in France.

However, glory did not last long for the esteemed scientist. On April 19, 1904, after leaving the Gauthier-Villars publishing house to return home, Pierre Curie was struck by a horse-drawn carriage, fatally injuring his head on Rue Dauphine in Paris. Pierre Curie was an outstanding physicist, one of the founders of modern physics. In memory of Pierre Curie, on May 13, 1906, the Sorbonne University invited Marie Curie to replace her husband as a lecturer. Marie Curie became the first female professor at the University of Sorbonne, Paris.

Marie Curie officially became a full professor at the University of Sorbonne in 1908. Also that year, she published a book titled The Works of Pierre Curie. In 1910, her work Treatise on Radioactivity (Traité de Radioactivité), a comprehensive 960-page volume, contained the most cutting-edge scientific knowledge of that era regarding radioactivity.

4. The Second Nobel Prize.

Marie Curie’s fame resonated globally. Numerous foreign universities awarded her honorary Doctorates.

In 1910, France intended to award Madame Curie the Knight’s Medal, but she declined, considering her late husband Curie’s attitude towards such honors. A few months later, many friends encouraged her to run for a position at the Academy of Sciences. Prominent supporters included the great scientist Henri Poincaré, Dr. Roux, Professor Emile Picard, and Professors Lippmann, Bouty, and Darboux. However, during the election, physicist Edouard Branly won the vote. Was it possible that the men at the Academy still harbored prejudices against women, preventing Madame Curie from being accepted? Once again, Sweden rectified France’s mistakes: in December 1911, Marie Curie was awarded another Nobel Prize in Chemistry for her work in discovering Radium. She remains the only individual to have received two Nobel Prizes, surpassing all scientists, both male and female, past and present.

In 1911, Polish intellectuals planned to establish a research center for radioactivity in Warsaw and intended to invite Marie Curie to lead this facility. In May 1912, a delegation of Polish professors traveled to France to meet her. At this time, Marie Curie was torn between her longing for her homeland and memories of Pierre, alongside her hopes for a Radium Institute being constructed in Paris. Ultimately, she sent a letter of refusal, expressing her confidence in the research capabilities of two Polish collaborators who had assisted her.

In 1911, Polish intellectuals planned to establish a research center for radioactivity in Warsaw and intended to invite Marie Curie to lead this facility. In May 1912, a delegation of Polish professors traveled to France to meet her. At this time, Marie Curie was torn between her longing for her homeland and memories of Pierre, alongside her hopes for a Radium Institute being constructed in Paris. Ultimately, she sent a letter of refusal, expressing her confidence in the research capabilities of two Polish collaborators who had assisted her.

In 1913, Marie Curie traveled to Poland to inaugurate the research center for radioactivity. She delivered a speech in her native language to a large audience. By July 1914, the Radium Institute in Paris was completed on Pierre Curie Street. This was the “Castle of the Future,” where Pierre had always wished to live to conduct research, and now Marie continued his legacy.

With the outbreak of World War I, unlike many women, Curie did not join the nursing corps; instead, she focused on the lack of X-ray facilities in hospitals. She equipped a car with X-ray machines and, alongside her daughter Irène, traveled to treat wounded soldiers on various fronts. As the number of injured soldiers increased, Marie Curie had to install 220 X-ray rooms both in the vehicle and on the ground. She even used her unique and invaluable Radium for treating war victims. Furthermore, the demand for radiology specialists prompted her to propose to the French Government the urgent establishment of a training course. This program was implemented at the Radium Institute, where lectures were given by Curie, her daughter Irène, and Marthe Klein.

In 1918, the war ended, bringing peace to France and independence to Poland after a century and a half of domination. For many years, Curie had devoted her energy and resources to the fight against foreign aggression. She donated her Nobel Prize money to the French Government. The war interrupted her research efforts and took a toll on her health.

In May 1920, Marie Curie received journalist William Brown Meloney. During their conversation, Curie mentioned her need for a gram of Radium to continue her research, which was prohibitively expensive. Moved and impressed, Meloney returned to the United States and launched a fundraising campaign among American women to purchase Radium for the female scientist. Meloney also invited Curie to the United States, but Curie was apprehensive about crowds and the publicity that fame brought. Eventually, she accepted the invitation. In early May 1921, Marie Curie, along with her two daughters, boarded the Olympic for America.

In May 1920, Marie Curie received journalist William Brown Meloney. During their conversation, Curie mentioned her need for a gram of Radium to continue her research, which was prohibitively expensive. Moved and impressed, Meloney returned to the United States and launched a fundraising campaign among American women to purchase Radium for the female scientist. Meloney also invited Curie to the United States, but Curie was apprehensive about crowds and the publicity that fame brought. Eventually, she accepted the invitation. In early May 1921, Marie Curie, along with her two daughters, boarded the Olympic for America.

On May 20, U.S. President Warren G. Harding graciously presented Marie Curie with a gram of Radium. In Philadelphia, she received honorary degrees, gifts, 50 grams of Mesothorium, and the John Scott Medal from the American Philosophical Society. Additionally, she was awarded honorary doctorates from the University of Pittsburgh and Columbia University. Curie returned to France on June 28 of that year.

Due to her invention of radiation therapy, in early 1922, the Academy of Medicine in Paris elected Curie as a member. In February of that year, she also became the first female scientist in the French Academy of Sciences. Marie Curie’s fame soared. She was warmly welcomed in Argentina, Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium, Czechoslovakia, and beyond. On May 15, 1922, the League of Nations appointed Marie Curie as a member of the International Educational Organization.

Marie Curie’s wish was to see a Radium Institute established in Warsaw. The project took shape in 1925, and she traveled to Poland to lay the foundation stone for the Institute. Once completed, the Radium Institute in Warsaw found itself lacking Radium for research. In October 1929, Marie Curie traveled to the United States once again. There, she received an exceptionally warm welcome, similar to her previous visit, and the United States once more supported the renowned female scientist. On May 29, 1932, the Polish Radium Institute was inaugurated according to the wishes of the illustrious scientist.

Even after turning 60, Marie Curie continued to work vigorously for 12 hours each day. Under her guidance from 1919 to 1934, 483 scientific papers were published by the physicists and chemists of the Radium Institute, including 31 authored by Curie herself.

By December 1933, Curie’s health began to decline. She had to follow her doctor’s advice regarding her diet, and occasionally, she returned to the countryside for a peaceful atmosphere. However, during an outing in May 1934, Curie caught a cold. Despite her doctor’s recommendation for rest, she continued to work, regretting lost time in the laboratory. Curie fell ill again, and her condition persisted for months. She was seen bedridden in a white outfit with snow-white hair, her high forehead and closed eyes revealing the toll that radiation had taken on her frail hands. Marie Curie passed away on July 4, 1934, at Sancellemoz Hospital, despite the dedicated efforts of renowned physicians. She died of leukemia caused by the radiation emitted from Radium.

By December 1933, Curie’s health began to decline. She had to follow her doctor’s advice regarding her diet, and occasionally, she returned to the countryside for a peaceful atmosphere. However, during an outing in May 1934, Curie caught a cold. Despite her doctor’s recommendation for rest, she continued to work, regretting lost time in the laboratory. Curie fell ill again, and her condition persisted for months. She was seen bedridden in a white outfit with snow-white hair, her high forehead and closed eyes revealing the toll that radiation had taken on her frail hands. Marie Curie passed away on July 4, 1934, at Sancellemoz Hospital, despite the dedicated efforts of renowned physicians. She died of leukemia caused by the radiation emitted from Radium.

On the afternoon of Friday, July 6, 1934, the funeral of the illustrious female scientist was held at the Sceaux Cemetery. Her coffin was placed on top of Pierre Curie’s grave, just as she had wished, to be close to her husband both in life and death.

Marie Curie was the first renowned female scientist in the world. She pioneered research on radioactivity. Besides her service to science, Marie Curie was also a passionate patriot, not only towards her homeland but also for the nation she recognized. Indeed, Marie Curie embodied the words of the great French writer Victor Hugo: “To serve the country is only half. The other half is to serve humanity.”