The bladder is a hollow organ that stores urine and is located in the pelvic cavity, outside the peritoneal cavity. When full of urine, the bladder takes on a spherical shape, with a capacity of approximately 250 to 350 ml in adults. The connective tissue of the bladder wall contains a lot of collagen structures, providing high elasticity, which means that in special cases, it can increase its capacity by up to 300% compared to normal.

|

|

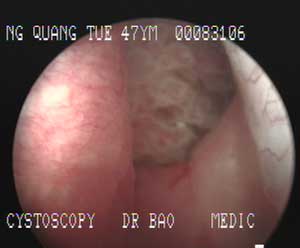

Image of a bladder affected by a tumor in a patient |

When the bladder has a capacity of around 350 ml, the pressure on the bladder wall is about 10 mmHg, which causes a sensation of urgency; above 400 ml, the feeling becomes very urgent, and at 600 ml, the pain becomes unbearable.

The act of urination is controlled by the nervous system centers located in the spinal cord regions S2 – S4, the cerebellum, and the cerebral cortex. In adults, a distended bladder will cause the sensation of needing to urinate. This sensation is consciously controlled by the cerebral cortex. When conditions are not right for urination, the cortex inhibits the reflex from the sacral spinal cord S2-S4. Conversely, the urge to urinate is transmitted from the cortex through sensory pathways to stimulate the reflex activity of the sacral nerves via the motor pathways at S2-S4, causing the bladder to contract and expel urine.

Bladder rupture is a surgical emergency; if not detected and surgically addressed in a timely manner, it can lead to peritonitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, pelvic abscess, retroperitoneal fibrosis, and even death due to shock. Most patients arrive at medical facilities late, complicating the clinical course of the disease.

Early diagnosis of bladder rupture is often challenging, especially in cases of extraperitoneal bladder rupture. The clinical presentation includes sudden lower abdominal pain, hematuria (blood in urine), etc. Ultrasound may reveal fluid in the abdominal cavity or extraperitoneal space, a smaller bladder volume, and may detect the rupture site. A retrograde cystogram showing contrast material leaking from the bladder allows for accurate diagnosis of bladder rupture.

Signs of spontaneous bladder rupture:

Rupture due to congenital defects or other bladder conditions

Some congenital defects and conditions can lead to weakened bladder walls, reduced elasticity, and smaller volume. An increased amount of urine in the bladder compared to normal can cause ruptures at pathological sites.

These defects and conditions include: bladder diverticulum, duplicated bladder, bladder septum, bladder shape abnormalities, bladder hypoplasia or agenesis, enlarged bladder, chronic cystitis, etc.

Rupture due to alcohol abuse

Spontaneous bladder rupture due to alcohol abuse is a very rare condition. High blood alcohol levels can suppress the cerebral cortex and certain neural centers controlling urination, leading to impaired consciousness so that the intoxicated individual does not feel the urge to urinate, causing the bladder volume to exceed permissible limits. The end result is bladder rupture.

Most cases of spontaneous bladder rupture due to alcohol reach the hospital late, making diagnosis and management very challenging.

Bladder rupture due to psychiatric disorders

In patients with psychiatric disorders, individuals may not feel the urge to urinate or may subconsciously convince themselves that they are not allowed to urinate. This can also be a cause of spontaneous bladder rupture.

Rupture due to cerebrovascular accidents, traumatic brain injury, and spinal cord injury

Brain tissue damage, such as infarction, hemorrhage, or trauma, especially in the cerebellar region, can easily lead to bladder rupture if a catheter is not placed beforehand. The reason is that the centers controlling urination in the cerebral cortex and cerebellum cannot command the urination reflex, causing increased bladder volume and subsequent rupture.

Spinal cord injuries can also cause spontaneous bladder rupture due to loss or inhibition of reflex pathways from the spinal cord to the brain and vice versa.