For a long time, scientists have wondered whether the eyes can retain the image of our last sight before we breathe our last.

It wasn’t until the invention of the camera that this intriguing topic was extensively studied.

Failed Experiments

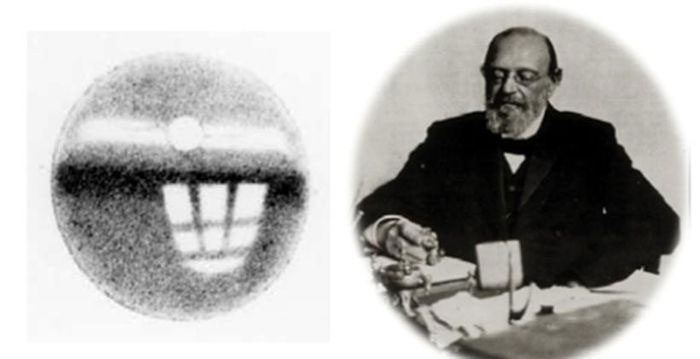

Scientist Wilhelm Kühne sees the image in the eyes of a rabbit immediately after it dies.

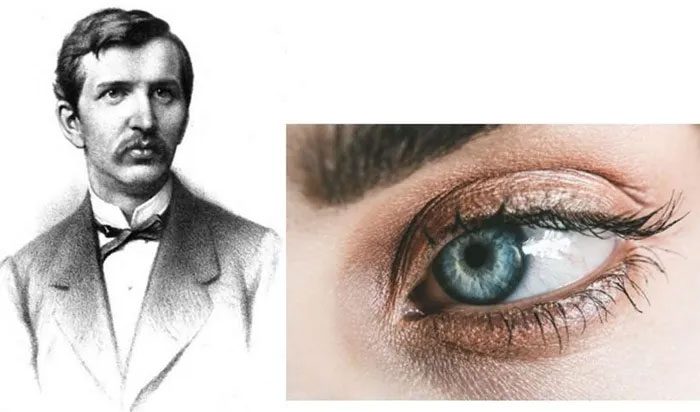

In 1876, German physiologist Franz Christian Boll discovered rhodopsin – a photosensitive protein in the rod cells of the retina, which behaves like nitrate on a photographic plate, capable of bleaching upon exposure to light.

Unfortunately, Boll’s life ended prematurely at the age of 30 due to tuberculosis, preventing him from further research. However, his findings were convincing enough for the scientific community to recognize that changes in rhodopsin play a crucial role in visual function.

After Boll’s death, one of his admirers, German physiologist Wilhelm Kühne, took up this discovery with “burning enthusiasm”. Kühne began experimenting on various animal species, quickly removing their eyes after death and using different chemicals to fix the images on the retina.

The following story from biochemist George Wald, who won the Nobel Prize in 1967 for his research on visual pigments, describes one of Kühne’s most successful experiments with a rabbit:

An albino rabbit was tied up, facing a barred window. From this position, the rabbit could only see the overcast gray sky. Its head was covered with a cloth for several minutes to allow its eyes to adapt to the darkness, enabling rhodopsin to accumulate in the rod cells.

Then, the animal was exposed to light for three minutes, after which it was beheaded to remove the eye, and the posterior half of the eyeball containing the retina was placed in a solution of alum for fixation. The next day, Kühne produced a photograph of the window with a clear pattern of the bars imprinted on the rabbit’s retina.

Kühne eagerly anticipated performing this technique on human subjects, and in 1880, an opportunity arose. On November 16, death row inmate Erhard Gustav Reif was taken to the guillotine for murder in the nearby town of Bruchsal.

Ten minutes after the execution, his eyes were removed and sent to Kühne’s laboratory at Heidelberg University. The optogram (the image from a deceased person’s eye) that Kühne created from Reif’s eye did not survive, but a sketch of what was seen on Reif’s retina appeared in Kühne’s 1881 article “Observations on the Anatomy and Physiology of the Retina.”

It did not resemble anything that the inmate could have seen at the moment of death. However, some speculated that the sketch resembled the guillotine’s blade, although the victim could not see it as he was blindfolded. Others suggested it might depict the stairs leading to the gallows. Kühne provided no explanation for the aforementioned images.

Physiologist Franz Christian Boll discovered the photosensitive substance rhodopsin, helping the eye function like a camera.

Prospects for Forensics?

Although Kühne did not obtain clear optical images from human eyes, the idea that the deceased retain their last images in their eyes continued to captivate the imagination of many during that time.

When it was suggested that optograms could be obtained from murder victims to help identify the killer, the Forensic Association in France requested Dr. Maxime Vernois to conduct a study to test the feasibility of using images from victims’ retinas as evidence in murder trials. Vernois killed 17 animals and dissected their eyes, but obtained nothing.

Despite Kühne and Vernois’s unsuccessful experiments, other researchers persisted in photographing the eyes of murder victims, hoping that these images could aid criminal investigations. Many detectives worldwide proposed applying this technique to victims in murder cases.

Rumors about the dead retaining their final images became so widespread that some murderers sought to destroy their victims’ eyeballs.

By the early 20th century, investigators had abandoned hope that optics could be developed into a useful forensic technique. However, in 1975, police in Heidelberg, Germany, enlisted scientist Evangelos Alexandridis from Heidelberg University to utilize modern scientific techniques, updated knowledge, and advanced equipment to revisit Kühne’s experiments and findings.

In Kühne’s method, Alexandridis attempted to create several high-contrast images from rabbit eyes. However, he concluded that optics did not have the potential to become a forensic tool.

This marked the final serious scientific inquiry into optics aimed at producing images from deceased humans. Nevertheless, the concept continues to persist in science fiction and detective literature.

Famous science fiction writer Jules Verne also maintained his belief in the potential of optics in criminal investigations through his 1902 novel “Les Frères Kip.” In the century that followed, this idea frequently appeared in literature and media. The 1936 film “The Invisible Ray” features Dr. Felix Benet, played by Bela Lugosi, using ultraviolet photography to capture images of a deceased victim’s eyes.