Black holes are a terrifying astronomical phenomenon that cannot be observed directly, but they can be detected through various physical solutions. They possess massive amounts of mass, potentially weighing several times that of the Sun, and have the ability to pull in surrounding objects.

For the first time, astronomers have discovered two supermassive black holes devouring material close to each other during a galactic merger event.

According to reports from the 241st meeting of the American Astronomical Society held in Seattle on January 9, two black holes – discovered by the Atacama Large Millimeter/Submillimeter Array (ALMA) in the Atacama Desert of Chile – are growing in tandem near the centers of two host galaxies in a merger event known as UGC 4211, located approximately 500 million light-years away from us.

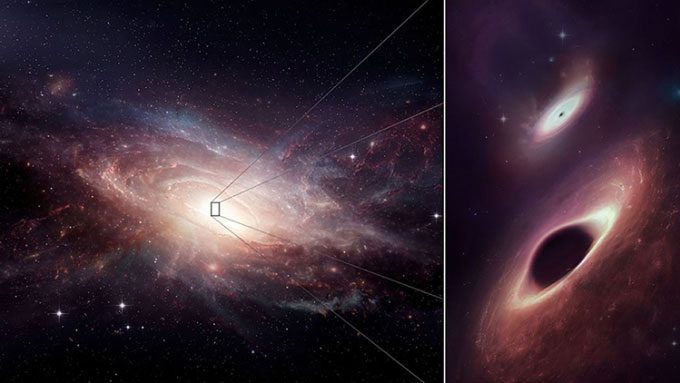

These supermassive objects weigh between 125 to 200 million times that of the Sun. Although the black holes themselves cannot be observed directly, they are surrounded by clusters of stars and glowing gas, which are drawn in by their extremely strong gravitational pull.

Simulation of the newly discovered black hole pair in UGC 4211. (Image: Michael Koss/ALMA/M. Weiss)

Analysis of the light wavelengths reveals that the two black holes are only about 750 light-years apart. This is the closest distance ever recorded for supermassive black holes.

“That distance is quite close to the limit we can detect, which is why this discovery is so exciting,” emphasized co-author Chiara Mingarelli, a researcher at the Center for Computational Astrophysics (CCA) at the Flatiron Institute in New York.

It is anticipated that the two black holes will begin to orbit each other, ultimately colliding and forming a larger black hole. This merger event will generate gravitational waves that are much stronger than any previously detected.

Galactic mergers often occur in the distant universe, making them difficult to observe with telescopes on Earth, but the ALMA observatory is an exception. Its sensitive array of antennas allows it to see through thick clouds of gas and dust to observe the nuclei of galaxies with high resolution.

This new discovery suggests that mergers between pairs of supermassive black holes may be more common than previously thought, opening up opportunities for future gravitational wave research.