The ancient rhinoceros species known as Embolotherium lived in Mongolia and other regions of East Asia, with most fossils found in the Gobi Desert.

Fossils are crucial for helping humans understand the past. With the Earth estimated to be about 4.543 billion years old, an unimaginable amount of life once called this planet home.

Five extinction events have wiped out many species on Earth, but fortunately, the fossils of these species can help us learn about the vast history of life.

This article will discuss an ancient rhinoceros species named Embolotherium, which is now extinct and also referred to as the “Thunder Beast”. Some may say that this creature resembles a failed creation of nature due to its uniquely shaped head, but there is much more to learn about them.

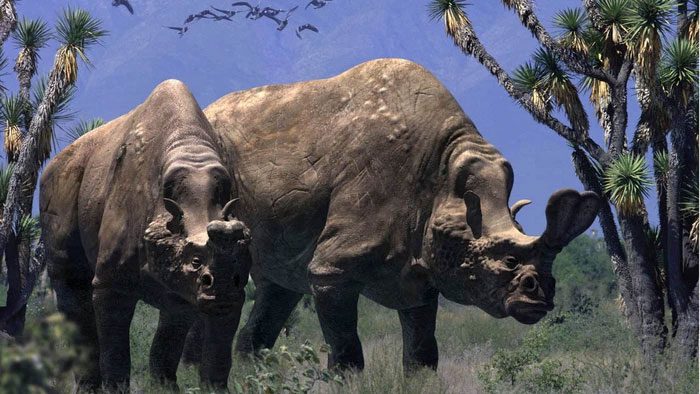

Among all ancient rhinoceros species, Embolotherium has the most unique “horn,” which truly resembles a wide, flat shield attached to the end of its snout.

Embolotherium is an extinct genus, with its name derived from Greek meaning “Thunder Beast.” This creature lived during the late Eocene epoch in East Asia.

Its name refers to the protrusion from its skull, making it look like a “faulty” version of a modern rhinoceros. However, they are actually distant relatives of animals such as horses, tapirs, and modern rhinoceroses.

Embolotherium is a very large ancient mammal, known only from incomplete fossil remains. So far, paleontologists have identified two species within this genus: Embolotherium andrewsi and Embolotherium grangeri.

Embolotherium is a very large ancient mammal, known only from incomplete fossil remains.

Although no complete fossils of Embolotherium have been found, there is ample evidence that allows for in-depth research on this ancient animal. In 1928, the first fossils of Embolotherium were discovered in the Ulan Gochu Formation in Inner Mongolia, China.

Funded by the American Museum of Natural History, American explorer Roy Chapman Andrews and paleontologist Walter W. Granger led an expedition to China to explore the fossils of ancient animals.

Fossils of Embolotherium’s jaws and skulls have also been found in the Baron Sog Formation and the Shara Murun Formation. Fossils of this animal are known only from East Asia, including discoveries in the Gobi Desert.

As they belong to the family Brontotheriidae, other animals like Megacerops from North America have helped scientists describe the appearance of Embolotherium. In early descriptions, researchers listed over a dozen species of Embolotherium, but further studies have reduced this number to just two species.

This strange “horn” structure may have been used to differentiate appearance (males with larger “horns” likely attracted more attention from females) or to resonate sound.

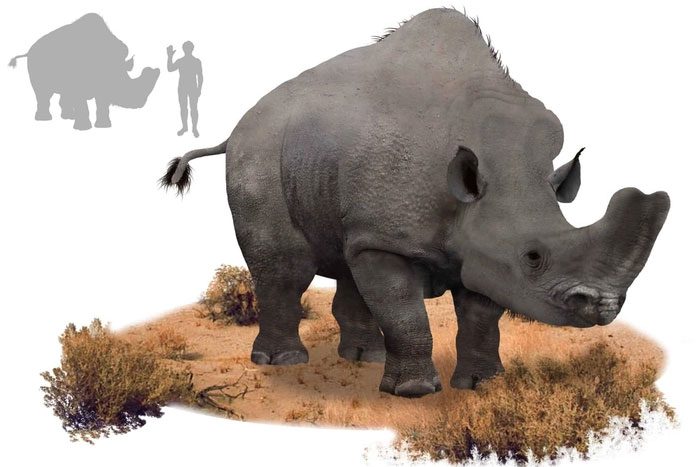

Despite the lack of complete fossils of Embolotherium, scientists have been able to estimate their size using existing data from other Brontotheriidae species like Megacerops.

Embolotherium is estimated to have stood about 2.5 meters tall and measured up to 5 meters in length, with an estimated weight of around 2 tons. The large bony protrusion extending from its face was about 70 cm long.

Descriptions of this animal indicate that it looked very much like modern rhinoceroses, but instead of horns, it had developed large nasal bones.

There is a hypothesis that the horn-like structure on its snout may have been used as a resonating chamber to amplify its sounds. All known specimens have nasal bones developed into a large plate.

Embolotherium lived during the late Eocene epoch in East Asia.

Embolotherium inhabited Mongolia and other areas in East Asia, with most fossils found in the Gobi Desert. This species lived during the Eocene epoch, approximately 41 to 34 million years ago.

During this time, the Gobi Desert had a landscape vastly different from today. The vegetation in this desert was lush, resembling a wetland habitat rather than the arid environment it is today.

The teeth of Embolotherium indicate that they were herbivores. They had cutting teeth rather than grinding teeth. Therefore, it can be inferred that they preferred soft-stemmed plants, requiring little chewing. The wetland habitat rich in soft vegetation was likely where this species thrived.

Despite their enormous size and significant development during the Eocene, Embolotherium went extinct at the end of the Eocene. The primary cause was climate change, as by the end of the Eocene, the region of Asia where these animals lived became drier.

The soft plants they fed on were replaced by drier, tougher vegetation, making them harder to eat. Other animal species attempted to adapt to the changing environment, but Embolotherium could not manage to do so, leading to its extinction.