Both space and time seem to be frozen inside it, behind the tin can, just waiting for someone to open it one day.

What would you do if one day you opened your refrigerator and found that the can of fish you bought at the supermarket was expired? Many people simply throw it in the trash. Or they might open it, dump the fish inside for their cat, and toss the tin can in a corner to wait for recycling.

But don’t be too quick to do that, as you could sell these expired cans of fish to scientists for a high price. The longer these expired fish cans are kept, especially if they have maggots inside, the more they become valuable treasures for the field of ecology.

By opening these expired fish cans, scientists are also opening time portals, allowing them to look into the marine ecosystems where the fish were caught decades ago.

Each expired can of fish, in that sense, is a miniature natural history museum. Both space and time seem to be frozen within it, behind the tin shell, just waiting for someone to uncover it one day.

Canned fish has a very long history.

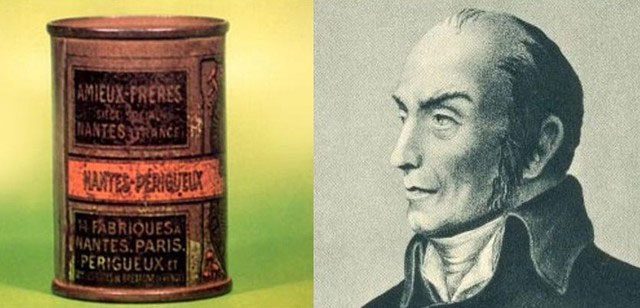

In case you didn’t know, canned fish has a very long history, first invented in 1795. It was during the Napoleonic Wars when the French emperor offered a reward of 12,000 francs to anyone who could come up with a method to preserve food for a long time.

Napoleon needed such food for his expeditionary army, which often had to fight far from home and for extended periods.

At that time, 12,000 francs was equivalent to more than 5 billion VND today. The prize was awarded to Nicolas Appert, a confectioner who devised a method to put fish in glass jars and then sterilize them by placing the jars in boiling water.

At that time, people were not aware of the existence of bacteria, so Appert could not explain why food spoiled and why immersing the glass jars containing fish in boiling water preserved the fish for longer. He just knew it worked.

It wasn’t until more than 50 years later, when another French scientist, Louis Pasteur, presented the germ theory, that bacteria and their role in food spoilage were understood.

Nicolas Appert, a French confectioner, invented canned fish in 1795.

But let’s return to the cans of fish. Initially, Nicolas Appert used glass jars to contain the fish, but the transportation process often resulted in broken jars. Therefore, an English merchant named Peter Durand came up with the idea of canning fish in tin containers.

This is when the canned fish we see today was created.

Both Nicolas Appert and Peter Durand can be considered the “Fathers of Canned Fish.” Initially, these cans of fish were only intended for soldiers during the war. However, later on, due to their long shelf life, lasting for years, they became a consumer product for all social classes.

However, perhaps when inventing canned fish, both Nicolas Appert and Peter Durand did not think that one day their product could be used for another purpose. That is scientific research; even when the cans of fish are expired and no longer edible, they still hold value.

Even when the cans of fish are expired and no longer edible, they still hold value.

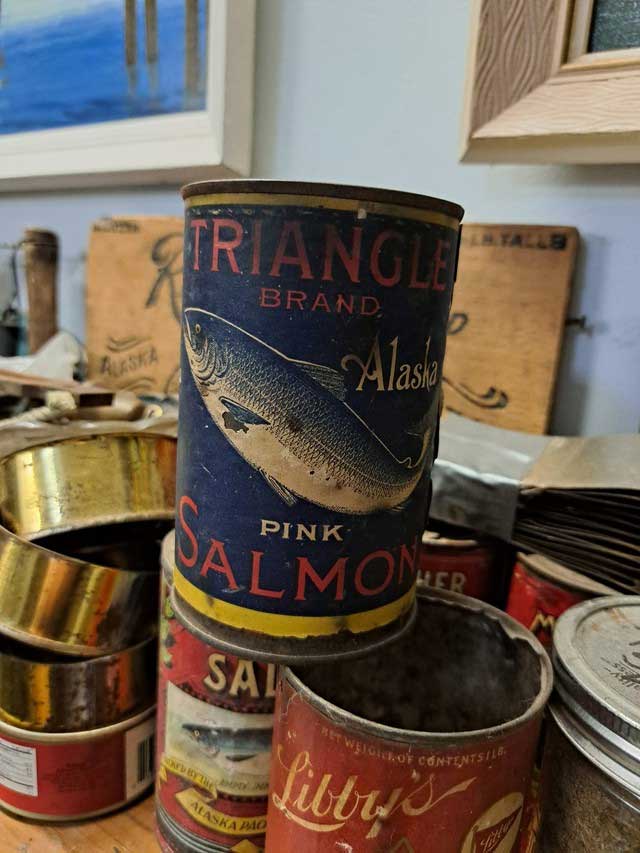

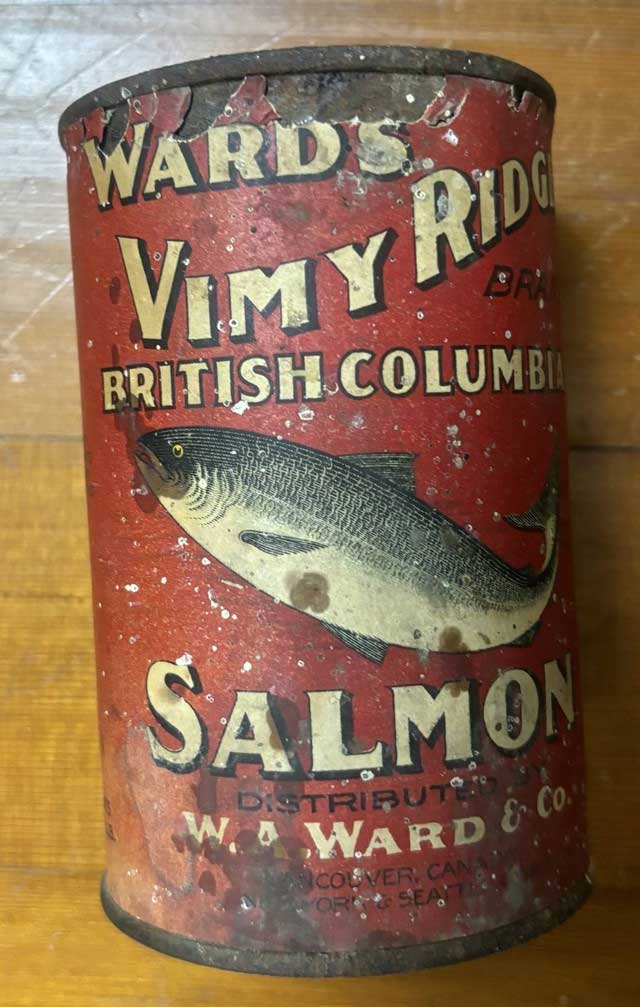

In a study published in the journal Ecology and Evolution, a group of ecologists at the University of Washington reported that they purchased 178 expired cans of fish at a high price from the Seattle Seafood Producers Association (SSPA).

These were surplus cans collected by SSPA annually from local producers during product quality control. Some cans were opened for analysis, while others were stored to see how long they could be preserved. Some were simply backup samples, collected as surplus, and have been in SSPA’s storage since the 1970s.

After all those years, on a day when SSPA decided to clean out the storage to prepare to throw away all the expired and unused cans of fish, they suddenly remembered Chelsea Wood, an assistant professor at the School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences, University of Washington, who had previously inquired about purchasing old cans of fish.

The seafood association staff asked Professor Wood if she would like to buy nearly 180 expired cans of fish. Like finding a treasure, Professor Wood’s answer was, of course, yes, she would buy them at any price.

But why are these expired cans of fish so valuable to scientists?

Professor Wood stated, the value of expired cans of fish lies not in the fish itself, but in the worms inside.

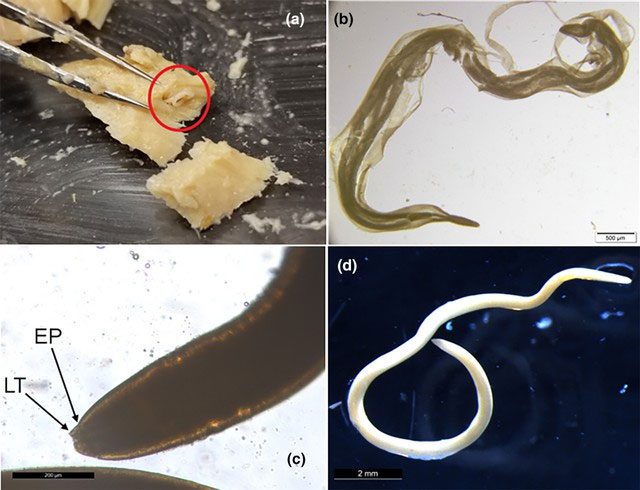

It turns out that inside the canned fish, there are still remains of worms. These marine worms belong to the parasitic anisakids species, each only about 1 cm long and have been killed during the sterilization process of the canned fish at a temperature of 130 degrees Celsius.

Although their remains are still inside the fish, they no longer pose a health risk to humans.

“People think that worms in salmon are a sign that the can has gone bad,” Professor Wood said. “But I see their presence as an indicator that your fish was harvested from a healthy ecosystem.”

A marine worm sample found in an expired can of salmon from the 1970s.

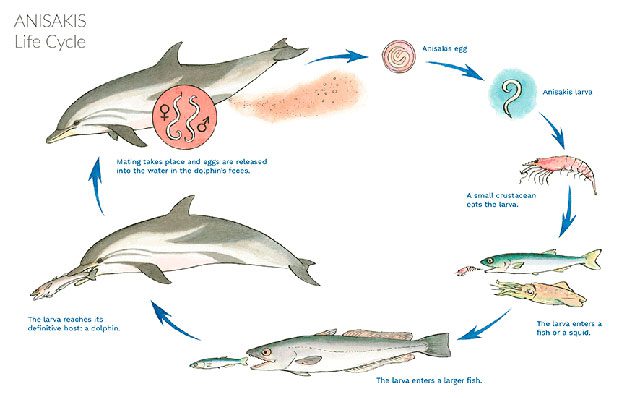

The fact is, marine worms play a crucial role in the ecosystem. They are initially food for plankton. Then, plankton is consumed by fish. Some worms or larval worms simply survive after being consumed by these species.

They then begin to parasitize and reproduce inside the fish’s intestines. These fish may then be eaten by larger fish, and even marine mammals. They will continue to reproduce, lay eggs, and then their eggs are excreted into the ocean by the fish. At this point, a new cycle begins.

“Without a host, marine worms cannot complete their life cycle, and their population will decline,” Professor Wood stated.

The life cycle of marine worms.

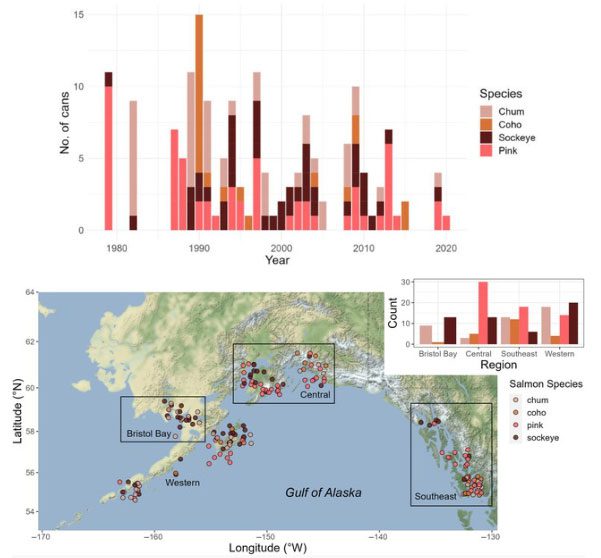

Therefore, with the 178 canned fish samples collected from the 1970s to now, her team simply opened them and counted the number of marine worm samples found inside. The samples included 42 cans of chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta), 22 cans of coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch), 62 cans of pink salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha), and 52 cans of red salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka).

The scientists found that the number of worms increased over time in chum salmon and pink salmon, but did not increase in red salmon and coho salmon.

“Finding an increasing number of marine worms over time, as seen in pink salmon and chum salmon, indicates that these parasites have found suitable hosts to reproduce,” Dr. Natalie Mastick, a co-author of the study from Yale University, stated.

“That could indicate a stable or recovering ecosystem, with enough suitable hosts for marine worms.”

Information about the number of marine worms in salmon samples allows scientists to map out an ecosystem in the areas of the Gulf of Alaska and Bristol Bay, where these salmon were caught.

By opening these expired cans of fish and counting the marine worms inside over time, scientists gained insights into the ecosystem in the waters of the Gulf of Alaska and Bristol Bay, where these salmon were harvested.

This is a remarkably novel marine approach and could open up many research directions, revealing even more information. Therefore, the question arising from this study is:

Do you have any expired cans of fish at home? Where were they produced, and from which waters were the fish caught? If you don’t plan to eat those expired cans of fish, don’t throw them away just yet; set them aside. You might be able to sell them to scientists for an unexpected price.