Biologists have described two new genera of tardigrades (water bears) and related species—two of which are new to science—from the glaciers of the Southern Alps in New Zealand.

First discovered in 1773, the water bear (phylum Tardigrada) is a group of extremely small, diverse invertebrates with eight legs, measuring from 50 to 1,200 µm (micrometers) in body size.

Commonly referred to as moss piglets, these creatures can live up to 60 years and are famous for their ability to survive in extreme conditions.

They can endure up to 30 years without food or water, survive for minutes at temperatures as low as -272°C (-457°F) or as high as 150°C (302°F), and can persist for decades at -20°C (-4°F).

Resembling a bear with eight legs and extremely small in size, tardigrades are found all over Earth—from damp places like moss, lichens, and leaves to soil and underwater environments. Tardigrades have truly astonished humanity with their survival capabilities, ranking among the toughest organisms on the planet. Furthermore, their extraordinary resilience is considered by researchers as a scientific foundation for responding to climate change.

They can withstand pressures nearly at 0 atm in space and can endure up to 1,200 atm at the bottom of the Mariana Trench, as well as resist radiation levels of 5,000-6,200 Gy.

Tardigrades inhabit various terrestrial environments (soil, bryophytes, lichens, algal mats) and aquatic settings (sediments, vegetation), from polar regions to tropical areas, high mountain peaks, and deep oceans.

Although tardigrades have been extensively studied worldwide, their diversity and ecosystem roles in frigid environments remain underappreciated, despite their significant contributions to food webs and ecosystem functions.

The richness of tardigrade species in extremely icy habitats is relatively low compared to surrounding ecosystems, possibly due to strong selective pressures including permanent low temperatures, high radiation, and periodic freezing.

Importantly, the tardigrade species found in glaciers are markedly different from their terrestrial counterparts, evidenced by genetic differences or phenotypic variations.

In 1773, a German pastor named J.A.E. Goeze first described this creature and named it Tardigrada, meaning “slow mover.” Three years later, Italian biologist Lazzaro Spallanzani also mentioned it. Tardigrades are very small, measuring only about 0.05mm-1.2mm. Their bodies are segmented, bilaterally symmetrical, and they reproduce either sexually or asexually. They feed on plant cells, animal cells, and bacteria. Additionally, they are preyed upon by amoebas, nematodes, and other tardigrade species. Tardigrades are called water bears because they resemble a bear with eight legs. Their habitats are diverse, often found in moist environments like moss, leaves, and lichens.

The lead author of the study, Dr. Krzysztof Zawierucha, a researcher at the Department of Animal Taxonomy and Ecology at Adam Mickiewicz University and the Faculty of Forestry and Wood Science at the Czech University of Life Sciences, along with colleagues from Poland, New Zealand, and the United States, stated:

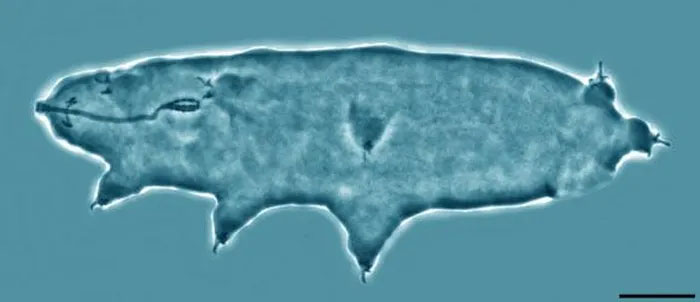

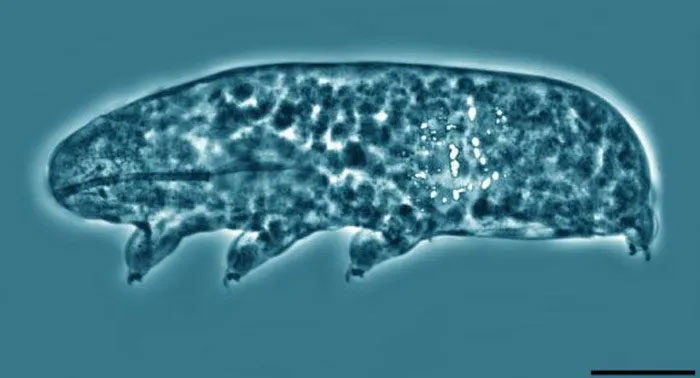

“The first genus, named Kopakaius, exhibits a special and unique morphology that has not been reported in the literature on tardigrades, while the second genus, Kararehius, is derived from the polyphyletic genus Adropion.”

The first genus is represented by three genetically distinct species, one of which, Kopakaius nicolae, is new to science.

The second genus includes a new species named Kararehius gregorii and three existing members of the genus Adropion: Kararehius behaviornae, Kararehius tricuspidatum, and Kararehius triodon.

To adapt to all living conditions from normal to the most extreme, water bears exist in three main states: active, anoxybiosis, and cryptobiosis. Under normal living conditions, tardigrades eat, grow, move, reproduce, and perform other life activities. In low oxygen conditions, they shift to anoxybiosis, during which they inflate their bodies and remain suspended for several days until environmental conditions normalize.

Like other high-altitude glacier tardigrades, Kopakaius tardigrades have dark pigmentation, while Kararehius lacks pigmentation, comparable to ice species in the Arctic and Antarctic.

Kopakaius nicolae is found only in the Whataroa Glacier, while the other two Kopakaius species inhabit the Fox and Franz Josef Glaciers, indicating low dispersal capability. Kararehius gregorii resides in the Fox and Franz Josef Glaciers.

The authors noted: “Cold environments not only serve as a repository for ancient invertebrate species preserved in frozen lands but also represent actively functioning ecosystems for diverse and resilient microbial forms, including tardigrades.”

“Tardigrades have been found on snow in forests, snowfields in barren mountain areas, as well as on the surface of ice at equilibrium line altitudes.”

“These findings establish a new direction for research on psychrophilic microorganisms, which will be crucial for describing and understanding the diverse, adaptive, dispersal, and evolutionary relationships between ‘cold-loving’ and ‘cold-tolerant’ invertebrates.”

“Our study contributes to this knowledge by revealing two new genera of tardigrades from glacial ice, their deep phylogenetic relationships in mitochondrial DNA, convergent evolution of morphological traits, and glacial fragmentation potentially causing traits during the Pleistocene epoch.”

Regarding reproduction, some tardigrade species reproduce asexually, while others are hermaphroditic and capable of self-fertilization. Thanks to this reproductive strategy, even under adverse conditions, water bears can still produce new populations when environmental conditions are favorable.