More than 100 years ago in China, during the 1920s, city dwellers knew how to “entertain themselves” more than you might think.

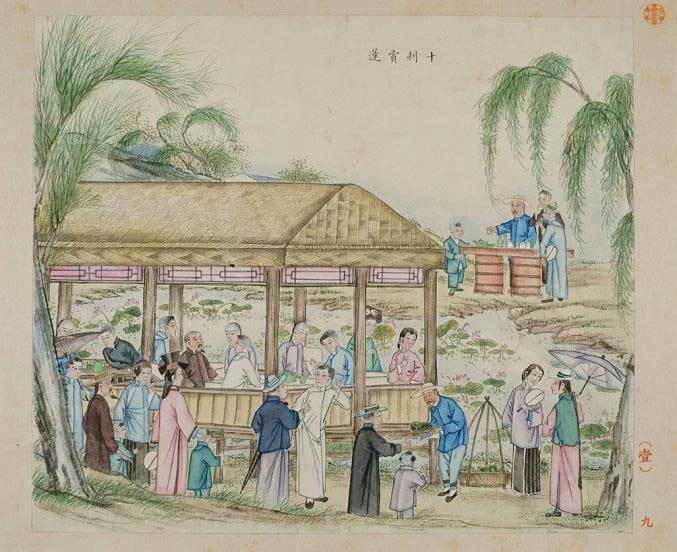

Evening Strolls at the Night Market

Unlike today, the term “nightclub” in the past referred to stalls where people would stop to browse while taking a leisurely walk after dinner. These stalls connected to form a night market.

Scene of goods displayed at the night market in the “Beijing Customs” painting series.

Many street vendors would light lamps and hold candles. The items sold were mostly folding fans, mirrors, handkerchiefs, and other daily necessities, priced slightly lower than in regular shops.

However, due to the insufficient light from candles, customers had to choose carefully to avoid purchasing low-quality goods.

A busy shopping area during the New Year.

This scene also occurred during the day, with street vendors displaying their goods and calling out along the streets. They sold flowers, puppets, feather dusters, candies, buns… a variety of items.

Stall owners would attract customers with friendly banter, while “waiters” invited guests to enjoy drinks and dishes. Everyone would haggle, exchanging money for goods, adding life and vibrancy to the streets.

Celebrating Festivals and the New Year with Traditional Beliefs

How do modern Chinese people celebrate festivals today? For instance, during the Dragon Boat Festival, people eat sticky rice dumplings and hang medicinal herbs (to ward off evil and prevent illness during the hot and rainy summer), while watching traditional performances on TV.

However, hundreds of years ago, the Chinese celebrated the Dragon Boat Festival in more elaborate ways. For example, men would use yellow rice wine to write the character “Wang” on their foreheads to ward off five poisonous creatures (snakes, centipedes, scorpions, poisonous frogs, and toxic geckos). Women would wear hairpins made of cloth shaped like tigers, gourds, or peach blossoms; these could also be tied to children’s chests to ward off evil.

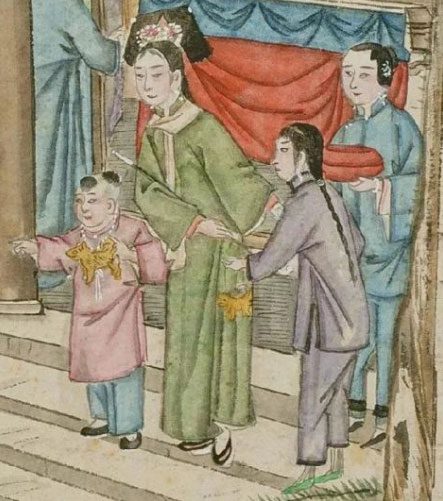

Cloth tiger.

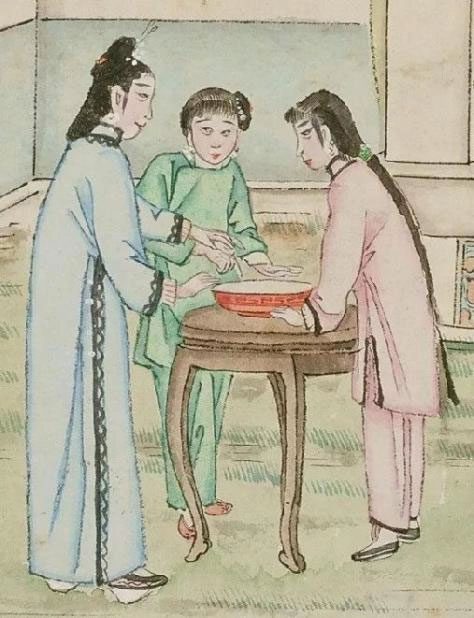

On the Qixi Festival, also known as the Double Seventh Festival, women would pour water into a large bowl and place it by the window, dropping a needle into it. If the needle floated on the water’s surface and cast a shadow like a flower at the bottom of the bowl, it indicated that the girl possessed skilled hands and talent in sewing and embroidery.

The custom of “Maiden Dropping the Needle” during the Qixi Festival.

During the Ming and Qing Dynasties, similar activities were very popular in both the imperial court and among commoners.

The painting Moonlit Travels by court painter Chen Mai in the Forbidden City and Qixi Festival Illustrated Book by Ren Baonian depict these customs.

On the 15th day of the seventh month each year, on a cool evening, adults and children would hold lotus lanterns, go to the riverbank, light candles, and release them into the river.

Releasing lanterns on the river.

“Releasing lanterns on the river” not only expressed the longing of people for their deceased loved ones but also contained well wishes for the living.

Diverse Daily Entertainment Comparable to Today

On ordinary days, the city of Beijing was just as lively as during festival seasons.

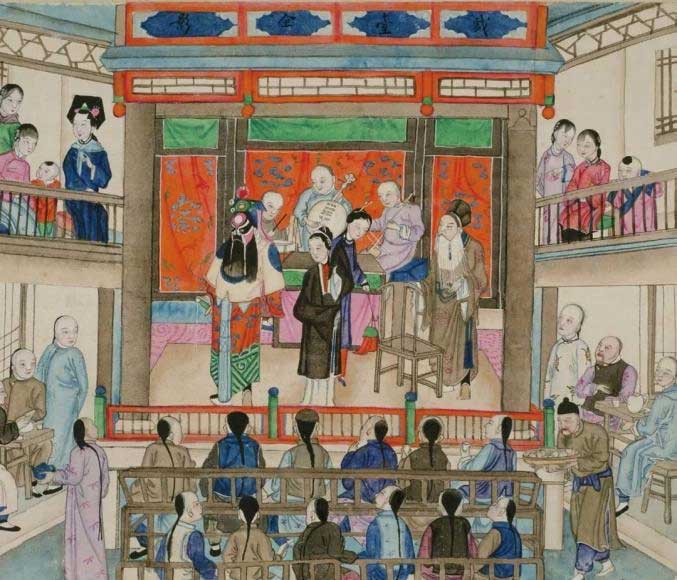

Tea house and theater.

People would gather at tea houses to chat, and many would congregate to play cards. A significant number of people sat in theaters, exclaiming “Wonderful, wonderful!” at traditional plays.

In summer, many would go to Shichahai to enjoy tea and view flowers, while in winter, they would play on the frozen ice.

Lotus viewing at Shichahai.

Winter games were not ice skating as in modern times, but rather “pulling the ice bed.”

“Ice bed” is approximately 1.6 meters long and 1 meter wide, usually made of wood, with iron bars on the bottom, capable of carrying 3-4 people, and can be larger depending on the budget of the players. The game organizer would shout “Pull!”, and the “ice bed” would be pushed by two workers using sharp sticks, allowing passengers to experience the thrill of sliding on the ice during the cold winter.

“Pulling the ice bed”.

The Beijing Customs painting series illustrates: The underside of the “ice bed” is simply nailed with a horizontal wooden plank, followed by a sheet of iron, and finally tightly tied together, being pulled by 1-2 workers. If they wanted to stop, the worker would jump down to slow down until it came to a complete stop. This was a game favored by the nobility in the palace.

The painting “Ice Fun” depicts nobles during the Qing Dynasty playing games on the ice.

In the Ice Fun collection stored in the Forbidden City, there is an image of the Emperor sitting on an “ice bed.” This indicates that the activity of playing on ice was popular nationwide, from commoners to royal family members.

Chinese folk customs from hundreds of years ago were thoroughly recorded by the Japanese sinologist Aoki Masaru.

In 1925, Aoki Masaru (38 years old) arrived in Beijing. He discovered that with the prosperity of Western culture, many traditional Chinese folk customs were gradually disappearing.

To preserve these valuable traditions, Aoki Masaru hired Chinese painters to create 117 paintings of Beijing customs, documenting the details of traditional Chinese festivals, including wedding and funeral rituals, daily necessities, clothing, food, entertainment, opera, and arts… This led to the creation of Illustrated Customs of China (later renamed Illustrated Customs of Beijing, translated as Beijing Customs Paintings).