AR3098, a large sunspot approximately 4 times the size of Earth, emitted a solar flare of 10 million degrees Celsius towards our planet at the end of September 12.

Before September 12, sunspot AR3098 had been present on the surface of the Sun for about 5 days. During this time, it became increasingly active, and scientists predicted a high likelihood of it emitting a solar flare.

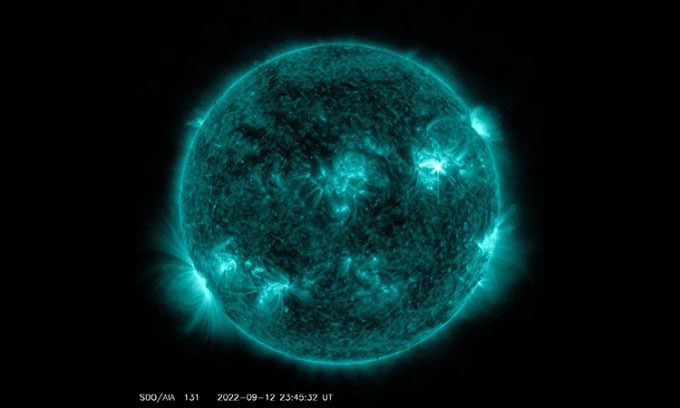

Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) captured an image of the Sun on September 12. (Photo: Alex Young).

Sunspots are regions with particularly strong magnetic fields—so strong that they inhibit some of the heat from within the Sun from reaching the surface. This makes sunspots appear darker and cooler than the surrounding areas. When the magnetic field associated with a sunspot suddenly shifts or reorganizes, a large amount of energy can be released. This energy bursts forth in the form of a radiation stream known as a solar flare, or a plasma cloud referred to as a coronal mass ejection (CME).

These solar material and energy releases can interact with Earth’s atmosphere and magnetic field, affecting modern technologies such as radio communication systems, navigation systems, and even power grids.

Experts classify solar flares into categories A, B, C, M, and X based on their strength, with X being the strongest and A the weakest. Typically, only M or X-class flares are powerful enough to prompt scientists to issue space weather alerts.

On September 12, AR3098 had a 70% chance of producing a C-class flare, a 20% chance of producing an M-class flare, and a 5% chance of producing an X-class flare, according to the website SpaceWeatherLive. By the end of the day, it appeared that an M-class flare had occurred. “AR3098 just emitted an M1.7 flare at the end of September 12 (UTC time). Data from the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) shows plasma hotter than 10 million degrees Celsius,” solar scientist Alex Young tweeted.

An M1.7 flare indicates its strength within the M category, where 1 is the lowest and 9 is the highest. Young noted that the M1.7 flare caused some temporary disruptions in the Pacific. It coincided with a two-minute burst of radio waves at 23:43 (UTC), according to the Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC) of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

SWPC stated that the radio wave burst was indicative of a solar flare and, although short-lived, it could still disrupt radar, satellite communication devices, and GPS. However, most people around the world would not notice the effects of the solar flare.