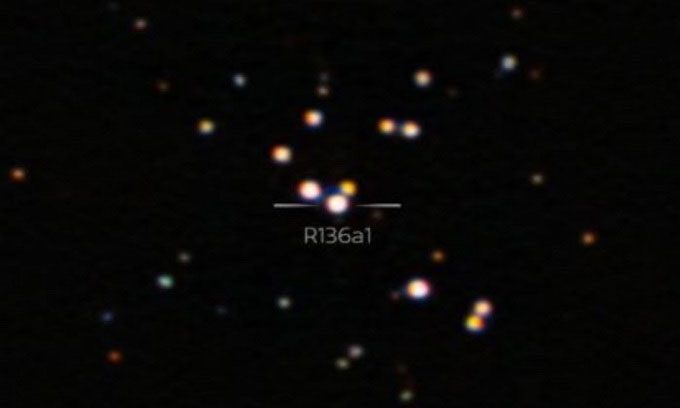

The clearest images of the star R136a1 help researchers make more accurate estimates of its mass.

Initially, the star R136a1 was thought to have a mass between 250 and 320 times that of the Sun. New estimates suggest its mass is actually between 150 and 230 times that of the Sun. Nevertheless, it still holds the record for the heaviest star known, according to recent research within the project studying the R136 star cluster. This star cluster is located in the Tarantula Nebula, a stellar “nursery” in the Milky Way’s satellite galaxy known as the Large Magellanic Cloud. The R136 cluster contains some of the largest stars ever discovered.

R136a1 captured by the Gemini South telescope. (Photo: Science Alert)

“The research results indicate that the heaviest star we know today is not as massive as we previously thought,” said astronomer and astrophysicist Venu Kalari at the Gemini Observatory. “This suggests that the upper limit for star sizes might be smaller than earlier estimates.”

The mass of a star can be calculated through precise observations that reveal its brightness and temperature. Therefore, Kalari and colleagues decided to gather clearer new images of the star cluster in general and R136a1 in particular using the Zorro instrument on the Gemini South telescope. This provided them with the means to determine a new mass estimate of 196 times that of the Sun for R136a1, and 151 and 155 times that of the Sun for two other massive stars in the cluster, R136a2 and R136a3.

The research findings have significant implications for the formation of heavy elements in the universe. These massive stars end their life cycles by becoming black holes. They shed their outer layers, and black holes form from the collapsing cores of these stars. However, with a mass of around 130 times that of the Sun, a star can explode in a supernova.

During that intense event, processes at the atomic level lead to the creation of heavy elements. If fewer stars exist within that mass range, we may need to rethink the contribution of supernova explosions to the creation of heavy elements in the universe.

The next step for researchers will be to test their conclusions by conducting observations with other instruments and comparing them with data from the Gemini South telescope. Their study has been accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal and is available on the arXiv database.