What is the reason behind this iconic shape? When a nuclear bomb detonates, energy is released chaotically in all directions. So why does the explosion create a mushroom cloud instead of an expanding fireball?

Katie Lundquist, a computational engineering researcher at the Lunsley Fermore National Laboratory in California, explained that although the initial explosion forms a “hot gas sphere”, as it begins to rise, the cylindrical core in the middle experiences greater buoyant forces than the surrounding area.

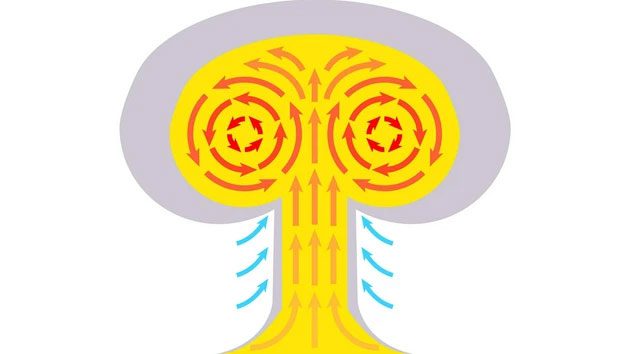

The sphere forms in this way because the fluid with the lowest density is at the center. It rises very quickly, similar to how a cupcake in an oven gradually heats up and expands. While the entire spherical fluid is rising, the substances in the middle ascend faster, causing the cooler air outside the sphere to start flowing downward.

This image shows the direction of fluid movement after a nuclear bomb explodes.

This causes the rising bubbles to spiral into a circular shape. Since the hot air molecules move faster and carry more energy, they collide at high speeds, ultimately creating a large space between them, resulting in an almost vacuum-like environment. The expelled material is sucked into the vacuum and then pushed upward, forming the mushroom cloud at the top and the flat region below.

The nuclear bombs dropped during wartime and related scientific experiments demonstrate that mushroom clouds can form on the ground, but what if a nuclear bomb were detonated in space? Would mushroom clouds still form?

The Baker Test nuclear bomb exploded in the Marshall Islands. This image was captured by an automatic camera on a nearby island. Note the mushroom cloud forming immediately after the nuclear bomb exploded.

The answer is that no mushroom cloud would form.

The mushroom cloud created by a nuclear bomb requires an atmosphere to activate the fluids, such as air. In the vacuum of space, there is very little air, and essentially, mushroom clouds cannot form. The airless environment on the Moon cannot produce a mushroom cloud.

Mushroom clouds also vary in shape and structure depending on the strength and altitude of the nuclear explosion; the mushroom clouds created exhibit different characteristics. The explosions that occurred in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, at the end of World War II had two main components: one part was a white cloud consisting of the vapor products of the explosion and water condensing in the surrounding air; the other part was brown material and debris. The body of the mushroom extends up from the ground, and one can see that these two parts do not completely touch each other.

On August 8, 1945, the U.S. military dropped an atomic bomb on Nagasaki, Japan.

When a nuclear bomb explodes, it creates a very clear white cloud, with a brown cloud underneath. The nuclear bomb was detonated at an altitude of about 610 meters above the ground, which explains the height of the cloud and the mushroom of the bomb.

Although nuclear bomb explosions can cause horrific damage, they do not have greater destructive power than later-manufactured weapons. According to the U.S. Department of Energy, the explosive yield of nuclear bomb detonations is approximately 20,000 tons of TNT, or even less. In contrast, the AN-602 hydrogen bomb (Tsar Bomba) produced in the former Soviet Union has a yield equivalent to 50,000 tons.

In stronger nuclear bomb test explosions that occur closer to the ground, the body and cap of the clouds generated by the explosion merge to form a typical mushroom-like structure.

|

A mushroom cloud is a cloud formed by the condensation of steam or debris from large explosions. They are often associated with nuclear explosions, although any sufficiently large explosion can create a similar effect. Conventional weapons with significant power, like thermobaric bombs or volcanic eruptions, as well as significant natural impacts, can also create mushroom clouds. The mushroom cloud results from the sudden formation of large, low-density, hot air currents near the ground, leading to the Rayleigh-Taylor stability effect. The hot air mass rises rapidly and moves in a swirling chaotic motion around the periphery, carrying smoke and debris that form the body of the mushroom. The rising hot air continues until it reaches stability, when the temperature drops and the density can no longer be lower than the surrounding air, at which point it spreads out, forming the cap of the mushroom before descending. |