For octopuses, their life journey ends after their first mating – which is also the only and final time. Scientists state that octopuses belong to the “semelparous” group, meaning they reproduce only once in their lifetime before dying.

The deaths of octopuses are programmed by nature in a systematic and incredibly cruel manner, at least from our human perspective. Male octopuses can be eaten by their mates. Alternatively, they also age and die within weeks after mating.

Female octopuses live a bit longer. This is because they have the task of laying and caring for the eggs. However, as soon as they sense that their eggs are about to hatch, female octopuses will stop hunting.

They may eat their own tentacles or even starve themselves to death. Some individuals even throw themselves against rocks or tear their bodies apart.

Why do octopuses eat their mates and then commit suicide?

Thus, at the moment the octopus eggs hatch, all of its offspring will be orphans, both fatherless and motherless. This is in stark contrast to other animal species, where the young are cared for by their parents until they reach maturity.

Ultimately, what drives octopuses to behave this way? How are they programmed by nature to die? Let’s explore in the article below.

The First and Last Date

The tragic story begins with a date when a male octopus meets a female octopus. It tidies its skin and tentacles to look presentable. Then the male approaches the female, getting close and touching her with its tentacles.

Octopuses are highly individualistic creatures; they never intend to touch each other or allow others to touch their bodies except in two scenarios: either they are fighting or mating.

If the female octopus rejects the male’s advances, the initial caress will immediately turn into a brawl. Female octopuses are typically larger than males, so the odds are usually in their favor.

If the female kills the male, she will drag his body back to her den and feast on it. Octopuses are, in fact, cannibalistic creatures.

Octopuses are cannibalistic creatures.

But let’s discuss a smoother scenario for the male octopus. If he creates a sweet and consensual atmosphere for the female, the two octopuses will proceed to mate.

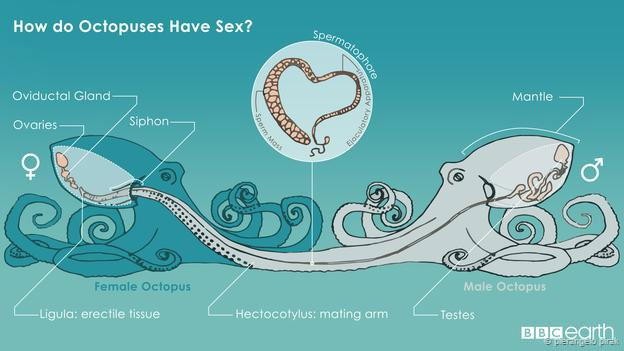

The male uses a special tentacle called “hectocotylus“, which has reproductive glands and testes. This tentacle differs in shape from the others, with a spoon-shaped indentation at the tip that contains modified suckers to release sperm.

Some octopus species will use the hectocotylus to directly inject sperm into the female’s oviduct opening, inside her mantle. However, in other species, the male merely deposits sperm cells into the female’s mantle, allowing her to fertilize them as needed.

Interestingly, some male octopuses even detach their hectocotylus tentacle and give it to the female to hold. Only after the female lays her eggs does she use this tentacle to spread sperm over them for fertilization.

How do octopuses mate?

However, no matter what, a male octopus knows that after mating, he will not live much longer. His body is programmed to age quickly afterward. He will grow old and die within just a few weeks.

Some even cannot hold onto life immediately after mating. About 15 minutes after the mating ritual, the female octopus will inch closer to the male. She uses her longer and larger tentacles to embrace her mate.

What seems like a passionate embrace is actually the male turning white. He is frightened and trying to escape. The female octopus does not relent; she wraps another tentacle around the base of the male’s mantle.

This prevents the male octopus from drawing water through his gills to obtain oxygen. Clearly, the female is choking her mate to death. Just about 2 minutes later, the male octopus stops struggling.

The female then drags the male back to her den. They will have a “romantic” dinner after the mating display. The only difference is that here, only the female gets to eat; the male has now become the female’s actual dinner.

The female octopus is typically larger than the male. She can strangle her mate to death.

Even Female Octopuses Are Programmed to Die

In fact, octopuses are not the only animals that kill their mates after mating. Moreover, among the more than 300 octopus species, not all of them eat their mates. However, this phenomenon occurs quite frequently and is not rare.

On land, we have female praying mantises that also eat their mates, and in some cases, male spiders actively sacrifice themselves to female spiders for nourishment, helping their offspring to be born healthier and in greater numbers.

Scientists indicate that female wolf spiders often lay over 30% more eggs after consuming their male partners. Similarly, female praying mantises eat males to gain calories during periods when they cannot hunt due to pregnancy.

Researchers believe these patterns have been similarly programmed in octopuses.

Additionally, octopuses do not view sex as an intimate act like humans and many other animals do. They simply see it as a duty. Thus, sex and feeding must be separated.

<pTherefore, after mating, when a female feels hungry, she tends to want to hunt for food. And since octopuses are cannibalistic, the prey closest to a female after mating turns out to be the male octopus.

There’s no reason to refuse a meal that has been served right to them.

An octopus caught eating another octopus

But even after mating and having consumed their partner, the fate of female octopuses is not much more optimistic.

Weeks after mating, the females begin to lay eggs. They care for their eggs very diligently. Female octopuses string their eggs together and attach them to the walls of their den.

Then, they blow water and oxygen onto the eggs daily to keep them alive. The female wraps around her eggs like a hen. She is ready to fiercely protect her den from any predators.

Depending on the species and reproductive conditions, octopus eggs will begin to hatch within 2 to 10 months. However, about a week before the eggs hatch, the female seems to sense this change. Erratic behaviors begin to emerge.

The female octopus suddenly separates from her egg clutch. She stops eating, self-harming by rubbing harshly against rocks or gravel at the ocean floor. As her tentacles tear, some octopuses even eat their own limbs.

Gradually, the octopus loses color and turns pale. Even in their eyes, there is no longer any vitality; perhaps they have gone blind. By the time the first eggs begin to hatch, all female octopuses have died.

Exactly why mother octopuses commit suicide remains a mystery to scientists. However, in a recent study published in Current Biology last week, a group of researchers at the University of Washington seems to have decoded it.

Octopuses care for their eggs very carefully, but before the eggs hatch, they will commit suicide.

Finding the “Self-Destruct” Button in Octopus Hormone Glands

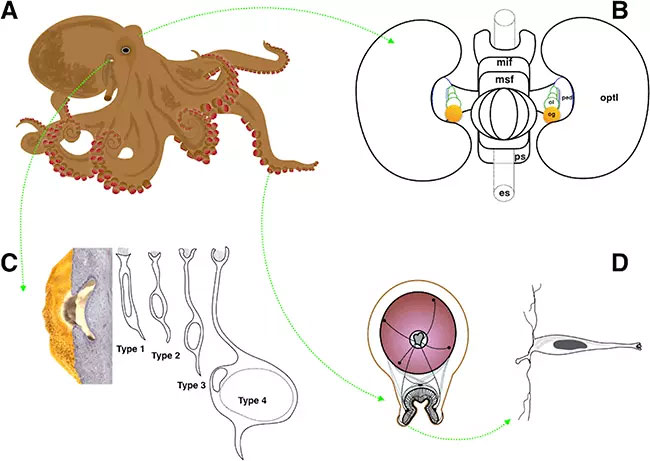

Dr. Z. Yan Wang, a psychology and biology associate professor and the lead author of the new study, stated that for a long time, other scientists have known that the reproductive and suicidal behaviors of female octopuses are governed by two visual glands of these creatures.

These are hormone glands that function similarly to the pituitary gland in vertebrates. They secrete hormones that regulate the maturity and reproduction of octopuses. Although called visual glands (due to their location between the two eyes of the octopus), these hormone glands have nothing to do with their actual vision.

In 1977, a psychologist named Jerome Wodinsky at Brandeis University conducted a classic experiment. He surgically removed the visual glands of female octopuses after they laid eggs. The result was that the octopuses no longer cared for their eggs.

Instead, the female octopus leaves her den and continues to hunt. They eat normally and continue to grow, with a significantly extended lifespan. Clearly, the optic gland has activated the “self-destruct” button, and if it were removed, the octopus could potentially live.

But is there a way to avoid surgery? A new study by Dr. Wang has now discovered the subtle chemical pathways occurring in the optic gland that compel female octopuses to commit suicide.

This is due to the secretion of a compound known as 7-dehydrocholesterol, abbreviated as 7-DHC. At an appropriate concentration, 7-DHC plays a crucial role in the development of octopuses. It is also produced in many vertebrate species.

The optic gland of the octopus, which contains its “self-destruct” button when secreting 7-DHC.

For humans, 7-DHC has various functions, including essential roles in cholesterol and vitamin D production. However, when the concentration of 7-DHC rises too high, ironically, it becomes toxic and is linked to disorders such as Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome—a rare genetic disorder characterized by severe intellectual, developmental, and behavioral issues.

In octopuses, Dr. Wang and colleagues suspect that 7-DHC is the essential factor causing self-harming behavior leading to the death of female octopuses. Therefore, if we could formulate a drug to block this compound and mix it into the water, theoretically, we could prevent female octopuses from committing suicide.

However, should scientists help octopuses “hack” into the process of creation? If they are programmed to die, there must be a reason.

From a human perspective, we view death as a failure of systems and organ functions. “But for octopuses, that is not the case,” Dr. Wang states.

“Death is something their system must undergo.“

Scientists note that female octopuses commit suicide after laying eggs to prevent themselves from eating their own offspring. Since they are programmed to be cannibalistic, a mother octopus may lack the maternal instinct to overcome her own predatory nature.

Whenever she sees a smaller octopus, she may view it as a meal instead of her own offspring.

In the end, the most pitiful are the newborn octopuses. They have lost both parents and must grow up on their own, maturing independently.

Another hypothesis suggests that octopus suicide after giving birth is a way for nature to prevent this species from overwhelming the ecosystem. This is because octopuses can grow without limits; theoretically, they could become gigantic versions like those seen in movies about deep-sea monsters or Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness.

But regardless, the deaths of both the female and male octopuses leave their offspring orphaned and adrift in the ocean. They will have to learn to swim, find food, and survive on their own without guidance.

The survival rate of juvenile octopuses is therefore only 1%, meaning that out of 100 eggs that hatch, only one octopus will grow to maturity. The octopus then seeks out a mate.

Depending on whether it is male or female, its fate will diverge in two different directions. However, both paths ultimately lead to one conclusion: A death pre-programmed by nature.