For decades, paleontologists have debated whether dinosaurs were warm-blooded, like modern mammals and birds, or cold-blooded, like modern reptiles. Understanding whether dinosaurs were warm-blooded or cold-blooded could provide insights into their activity levels and daily lives. In a new paper published in the journal Nature, scientists have revealed a novel method to study the metabolic rates of dinosaurs by examining clues found in their bones.

“This is truly exciting for us as paleontologists – the question of whether dinosaurs were warm-blooded or cold-blooded is one of the oldest questions in paleontology, and now we think we have reached a consensus that most dinosaur species were warm-blooded,” said Jasmina Wiemann, the lead author of the paper and a postdoctoral researcher at the California Institute of Technology.

Dinosaur bones are clues for studying the metabolic rate of dinosaurs.

“The new proxy developed by Jasmina Wiemann allows us to directly infer the metabolic processes in extinct organisms, something we had always dreamed of before.” Matteo Fabbri, a postdoctoral researcher at the Field Museum in Chicago and one of the study’s authors, noted that different metabolic rates characterize different groups.

Sometimes, metabolism is discussed in terms of how easily a person can maintain their physique, but at its core, “metabolism is how we efficiently convert the oxygen we breathe into chemical energy that powers our bodies,” Wiemann, an expert affiliated with Yale University and the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, explained.

Cold-blooded animals have a less energy-intensive lifestyle compared to warm-blooded animals. (Illustrative image).

Animals with high metabolic rates are thermoregulators, or warm-blooded; warm-blooded animals like birds and mammals take in more oxygen and must burn more calories to maintain body temperature. Cold-blooded animals, like reptiles, breathe less and eat less compared to warm-blooded animals. Their lifestyle is less energy-intensive than warm-blooded animals, but they rely on the external environment to keep their bodies at the appropriate temperature for activity (like lizards basking in the sun), and they tend to be less active than warm-blooded organisms.

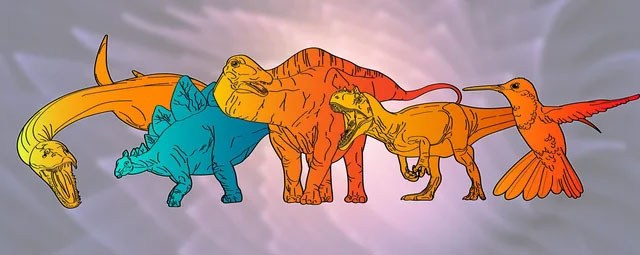

With birds being warm-blooded and reptiles cold-blooded, dinosaurs have been caught in the middle of this debate. Birds are the only dinosaur lineage that survived the mass extinction at the end of the Cretaceous period, yet dinosaurs are fundamentally reptiles. So, what is the reality? Were dinosaurs warm-blooded or cold-blooded?

Were dinosaurs warm-blooded or cold-blooded?

Scientists have attempted to gather metabolic rates of dinosaurs through chemical analyses and studies of their bones. Wiemann stated, “Previously, dinosaur bones were examined using isotopic geochemistry similar to a classic thermometer” – researchers analyzed minerals in a fossil and determined the temperature at which those minerals would form. But we realized that we didn’t truly understand how fossilization alters isotopic signals, making it difficult to clearly compare fossil data with modern animals.”

Instead, they focused on one of the most fundamental indicators of metabolism: oxygen usage. When animals breathe, byproducts react with proteins, sugars, and lipids, creating what can be termed as “waste” molecules. These waste products are very stable and insoluble in water, thus preserved in fossilization processes. They record the amount of oxygen that dinosaurs inhaled, and therefore their metabolic rate.

The researchers searched for these molecular waste fragments in dark-colored fossil specimens, as these darker colors indicate that a significant amount of organic material has been preserved. They examined the fossils using Raman and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy – “these methods work like laser microscopes, essentially allowing us to quantify the abundance of molecules and learn about metabolic rates,” Wiemann explained.

The research team analyzed samples from 55 different animal groups, including theropod dinosaurs, pterosaurs, plesiosaurs, as well as modern birds, mammals, and lizards. They compared the quantities of respiratory-related molecular byproducts with known metabolic rates of living animals and used that data to infer the metabolic rates of extinct species.

The metabolic rate of dinosaurs is generally high.

The research team found that the metabolic rate of dinosaurs is generally high. There are two major groups of dinosaurs, saurischians and ornithischians – lizard-hipped and bird-hipped. Bird-hipped dinosaurs, like Triceratops and Stegosaurus, exhibited metabolic rates equivalent to modern cold-blooded animals.

Lizard-hipped dinosaurs, including bipedal predators like Velociraptor and T. rex, as well as long-necked, massive herbivores like Brachiosaurus, were all warm-blooded creatures – their metabolic rates were comparable to those of modern birds, significantly higher than those of mammals.

The researchers noted that this discovery could provide fundamental insights into how dinosaurs lived. Reconstructing the biology and physiology of extinct species is one of the most challenging tasks in paleontology. The new study could infer body temperature from isotopes, growth strategies from bone histology, and metabolic rates from chemistry.

The researchers emphasized that understanding how modern and extinct animals physiologically responded to past climate changes and environmental disruptions is crucial for informing current biodiversity conservation efforts and guiding human actions in the future.