In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many cities and states in the United States enacted laws prohibiting individuals with physical disabilities from appearing in public.

In July 1867, Martin Oates, a veteran of the American Civil War (1861 – 1865), was detained by police while walking the streets of San Francisco, California, appearing in a state of “poverty, illness, and insanity”. This action was based on an ordinance passed by the San Francisco government, which banned individuals like Oates – “ill, deformed, crippled, or having physical deformities that frighten others” – from appearing in public; violators faced fines of up to $25 (approximately $400 today), 25 days in jail, or commitment to a poorhouse.

Three men with peculiar appearances. (Photo: Wellcome Collection)

According to Professor Susan Schweik from the University of California, Berkeley, San Francisco was the first city in the U.S. to enact Ugly Laws, which Chicago in Illinois followed (in 1881); Denver, Colorado and Lincoln, Nebraska (1889); Columbus, Ohio (1894); Portland, Oregon (1881); New Orleans, Louisiana (1883), and so on. Notably, Pennsylvania implemented it statewide in 1891, covering not only those with physical disabilities but also those with cognitive impairments. Meanwhile, both New York City and Los Angeles attempted to adopt similar regulations but ultimately failed.

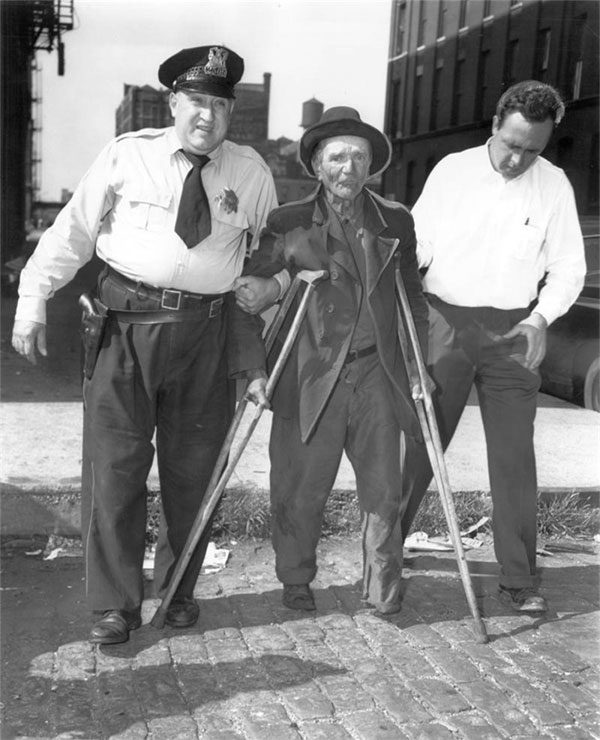

Chicago police escorting a person with a leg disability to the station in 1954. (Photo: Luigi Mendicino / Chicago Tribune).

Initially, such legal texts were often seen as tools for authorities to address the rise of begging and maintain urban aesthetics. It was only later that the term Ugly Laws emerged, not to evaluate the appearance of citizens, but essentially as a form of legal discrimination. Lawmakers hoped that these new regulations would “remove” the impoverished, disabled, and deformed individuals (often prone to begging) from public view, thereby contributing to public order, preserving aesthetics, and reducing social tensions.

Several factors led to the emergence of these regulations. The first was the massive wave of immigration (mostly poor individuals) to major urban areas, creating chaotic public scenes. Additionally, after the Civil War, many wounded veterans who could no longer work resorted to begging in large cities, with numerous impostors taking advantage of the situation, making it even harder to control. Furthermore, a moral perspective rooted in religious (Protestant) beliefs – emphasizing individualism and the notion that people should take care of themselves, along with the inadequacies of healthcare and welfare systems, were also significant factors.

A blind beggar in a wheelchair in Lawton, Oklahoma, in 1917. (Photo: Lewis Hine/Library of Congress).

Although the enactment and enforcement of such laws diminished during World War I (1914 – 1918), legal texts remained in effect for many decades afterward. The last recorded use of Ugly Laws for arresting violators occurred in 1974 in Omaha, Nebraska. According to records in the Cleveland archives regarding this incident, an Omaha police officer sought to arrest a beggar without just cause; after “digging through” numerous legal documents, he discovered that the Ugly Laws were still in force and detained the beggar for having “many scars and marks.” Disagreeing with this conduct, the prosecutor stated in court that while the law was still in effect, the prosecution lacked grounds due to insufficient evidence to prove the “ugliness” of the defendant; authorities subsequently could not bring charges.

Despite being outdated, many Ugly Laws remained in effect until the late 1970s. In 1974, Chicago was the last city in the U.S. to repeal the ordinance after it had been in place for 93 years. By 1990, the federal government finally enacted The Americans with Disabilities Act after extensive advocacy by individuals and social organizations. This law was established to protect the rights of individuals with disabilities, ensuring they would no longer face discrimination due to physical or psychological impairments, and granting them equal opportunities for employment, access to public services, and common spaces.

Fortunately, these inhumane laws did not spread from the U.S. to other countries. However, in 1902, the city of Manila (Philippines), then under American rule, enacted an ordinance banning beggars from operating, citing public aesthetic concerns, which was entirely written in English.