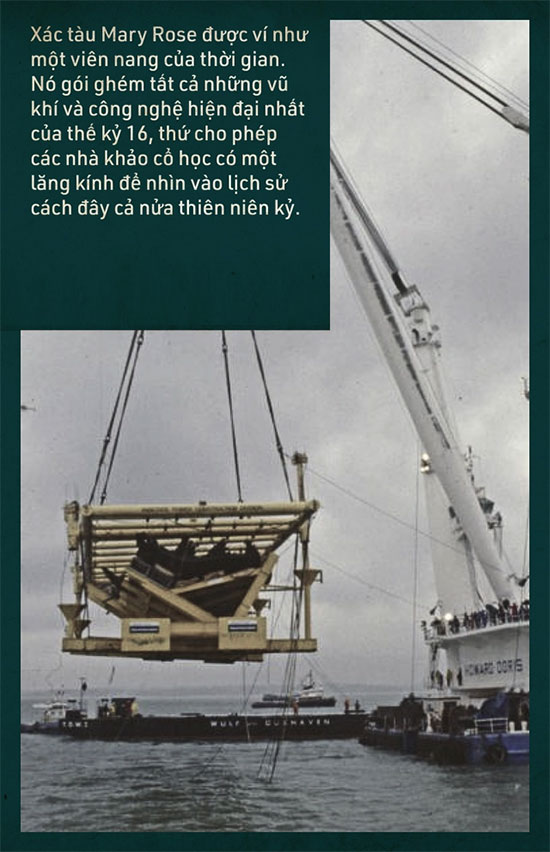

On October 11, 1982, at the Solent Strait between the Isle of Wight and the mainland of the United Kingdom, hundreds of eager eyes were focused on the enormous floating crane of the marine construction company Howard Doris.

The crowd included a group of divers, royal engineers, archaeologists, and notably, the presence of Prince Charles. They were there to witness one of the most complex and costly maritime salvage operations in human history: The Wreck of the Mary Rose.

The Mary Rose was a carrack-class warship of the English navy, built and launched in 1511. It served the Royal Navy for 34 years, from the reign of King Henry VIII until it sank during a naval battle with France in 1545.

The ship sank in the Solent Strait, burying over 400 crew members along with tens of thousands of artifacts for four centuries.

Thus, the Mary Rose is likened to a time capsule, encapsulating all the most modern weapons and technologies of the 16th century, allowing archaeologists a lens through which to view history from half a millennium ago.

More than 26,000 artifacts and pieces of wood have been recovered alongside the Mary Rose since then. Among the guns, cannons, jewelry, and musical instruments, archaeologists also paid attention to items found in a room known as the Barber-Surgeon’s Cabin.

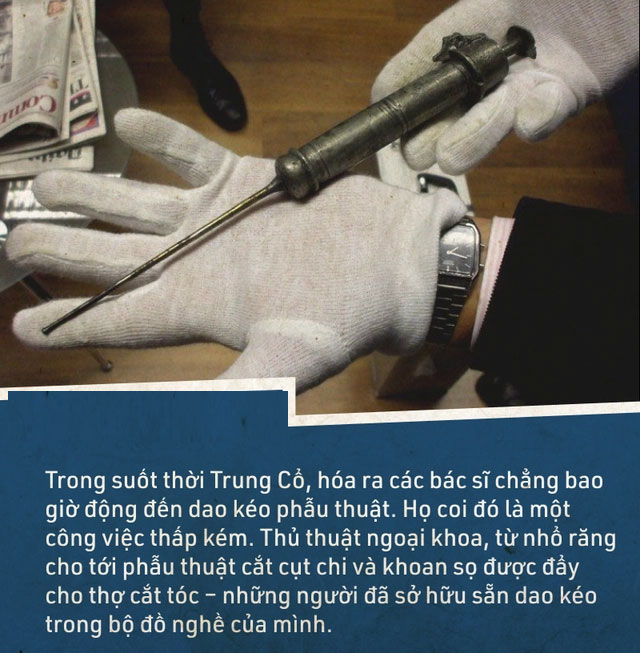

Throughout the Middle Ages, it turns out that surgeons never actually used surgical instruments. They considered it a lowly job, merely involving mechanical intervention on the human body. Moreover, surgery was associated with high mortality rates, and doctors did not want this work to tarnish their scholarly reputation.

Surgical procedures, from tooth extraction to amputations and trepanation, were left to barbers – who already had knives and tools in their kits.

On a warship like the Mary Rose, such barber-surgeons were indispensable. They were responsible for caring for and operating on injured sailors.

Examining the barber-surgeon’s cabin on the Mary Rose allows archaeologists to reconstruct the medical practices of the 16th century.

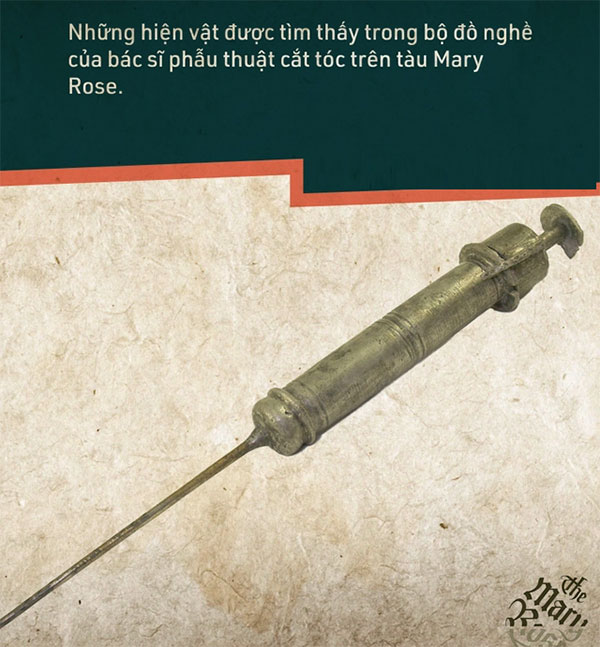

They found a total of 60 medical instruments, including a mallet (used to strike the back of a scalpel when cutting bone), a brass cautery (used to burn flesh and seal wounds), and a trephine (used to bore holes in the skull to relieve fluid and blood buildup).

Medieval Medical Instruments.

This is how 16th-century medicine operated. But in today’s story, let’s focus on a copper syringe with a very long needle that was also found in the kit of the barber-surgeons aboard the Mary Rose.

This syringe was used to treat gonorrhea.

1. Gonorrhea in the Pre-Antibiotic Era

Gonorrhea is a sexually transmitted disease (STD) caused by the Neisseria gonorrhoeae bacterium. This gram-negative bacterium was first isolated in 1878 by German physician Albert Neisser, after whom the gonorrhea bacterium was named.

However, gonorrhea has existed for a long time alongside human history. It may be one of the earliest known sexually transmitted diseases.

Ancient Chinese medical texts recorded a disease similar to gonorrhea during the era of Huang Ti (2600 BC). The Book of Leviticus, the third book of the Hebrew Bible and the Old Testament, also mentions gonorrhea.

Hippocrates, the father of Western medicine, referred to gonorrhea as “the pleasure of Venus” in writings from his time (around 460-375 BC). However, the term gonorrhea was coined by Galen, a Greek physician, around 131-200 AD.

Gonorrhoeae is a compound of “gono” in Greek meaning “seed” and “rhea” meaning “flow”. The disease was described by Galen as “unwanted semen discharge.”

In reality, this is a clinical symptom of gonorrhea, but Galen was mistaken; the discharge from the penis of men with gonorrhea is not semen, but pus caused by the infection.

Doctors in the past attempted to remove this pus by slapping both sides of the patient’s penis with their hands. They might even place the penis on a hard surface and strike it with a large book to force the pus out.

Because of this extreme treatment method, gonorrhea was also nicknamed “The Clap,” meaning the disease that must be clapped.

Treatment methods for gonorrhea became more advanced in the 16th century, but they were still very painful. Like the syringe found on the Mary Rose, which was used to inject mercury into the urethra of infected sailors.

As mercury has antibacterial properties, it could kill the bacteria, but ironically, mercury itself is a poison, and injecting it into the urethra left many terrible side effects, from skin inflammation and mucosal irritation to kidney damage.

Thus, by the 18th century, the practice of injecting mercury into the penis was replaced by warm water. It turned out that gonorrhea bacteria are very sensitive to high temperatures, so if the infection was mild with little discharge, doctors could simply use the syringe to inject warm water at 46-50 degrees Celsius into the patient’s urethra. After 2-3 days of continuous washing like this, gonorrhea could subside.

By the 19th century, silver nitrate, which has antibacterial properties and does not leave side effects, was used to treat severe cases of gonorrhea, along with mercurochrome, a derivative of fluorescein with bromine and mercury.

However, regardless of the solution used, treating gonorrhea before the antibiotic era posed many risks, side effects, and caused pain for patients.

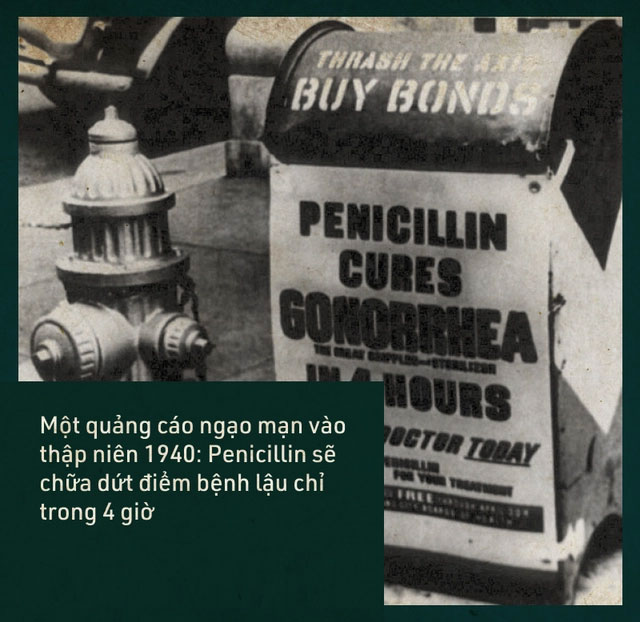

Things only changed after Alexander Fleming discovered Penicillin, the first antibiotic for humans.

2. In the Age of Silver Bullets

This is how antibiotics were referred to during their golden age. After Penicillin was developed in 1943, antibiotics were used to treat all bacterial infections.

Penicillin exhibited extraordinary efficacy. From severe infected wounds that previously required amputations to urinary tract infections like gonorrhea, just a few days of antibiotic treatment would cure the infection.

Doctors could now say goodbye to their urethral syringes and prescribe a few days of antibiotics for gonorrhea patients. But the golden age of antibiotics turned out not to last very long.

In 1943, when Penicillin was introduced, by 1945, Penicillin-resistant bacteria had already emerged. These strains of bacteria had evolved in the antibiotic environment to render the drug ineffective.

By 1946, at least four cases of Penicillin-resistant gonorrhea had been reported. By 1963, a new antibiotic, Ampicillin, was used to replace Penicillin. This new drug could cure up to 98% of gonorrhea cases.

However, the evolution of bacteria and antibiotics has always resembled a game of leapfrog. When humans discover a new antibiotic and introduce it into treatment, drug-resistant bacteria emerge shortly thereafter. As a result, we must again struggle to find a new antibiotic.

Over six decades, gonorrhea bacteria have evolved to resist nearly all types of antibiotics used by humans, from cotrimoxazole, chlortetracycline, spectinomycin, cephalosporin to erythromycin, and ciprofloxacin…

In 2007, ceftriaxone was considered the “last line of defense” for humans against gonorrhea, which had become resistant to antibiotics. After this drug, it was confirmed that no antibiotics were left for humans to combat the Neisseria gonorrhoeae bacteria.

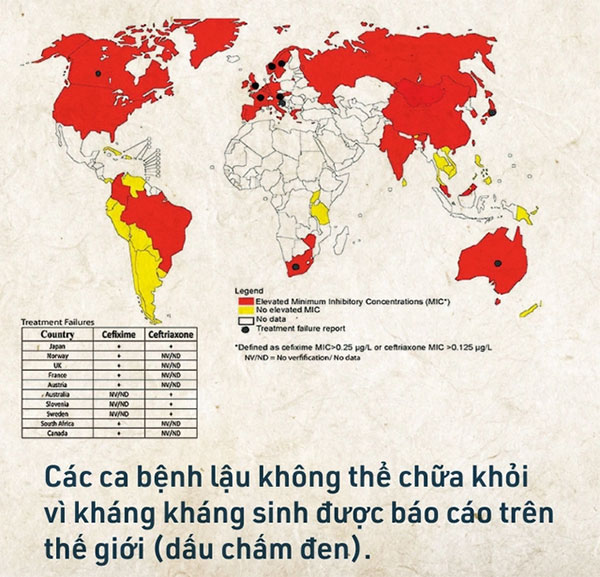

In 2018, British scientists reported the first case of untreatable gonorrhea. This was a man who contracted the disease after traveling to Southeast Asia.

He was prescribed two antibiotics: oral azithromycin and injectable ceftriaxone. However, neither drug was effective. As a result, doctors had to closely monitor this man and his partner in the UK to contain the spread of the resistant gonorrhea strain.

But in February of this year, three more cases of antibiotic-resistant gonorrhea were reported in the UK. Additionally, other countries such as China, Japan, France, Spain, and Australia also identified cases of this resistant gonorrhea.

According to a report from the World Health Organization (WHO), 97% of countries surveyed between 2009 and 2014 reported finding drug-resistant gonorrhea strains. Among these, 66% reported the emergence of gonorrhea resistant to the last-resort antibiotics.

This is a sign that the golden age of antibiotics is coming to an end, and we stand on the brink of a dark era known as the post-antibiotic phase.

3. When Gonorrhea Has No Cure

300,000 deaths due to drug-resistant gonorrhea each year is the prediction of Teodora Wi, an expert in sexually transmitted diseases at WHO, regarding what will happen in the post-antibiotic era.

This figure adds to a prediction of up to 10 million deaths from all types of drug-resistant bacteria by 2050. Right now, that number is already over 700,000.

WHO states that currently, nearly 80 million cases of gonorrhea are recorded globally among adolescents and adults each year. This number could be even higher as many countries do not fully report cases.

The rate of gonorrhea bacteria resistant to both first-line antibiotics, azithromycin and ceftriaxone, in some reporting countries, such as China, is 3.3%. The figures are even higher, with 19% resistance to azithromycin and 11% resistance to ceftriaxone.

Untreated gonorrhea can lead to many dangerous complications. For instance, drug-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae can cause epididymitis and infertility when it invades the vas deferens.

Similar consequences occur in women when the bacteria attack the uterus and fallopian tubes. Newborns infected with gonorrhea from their mothers during childbirth can suffer from blindness, scalp ulcers, or infections.

Additionally, when gonorrhea bacteria enter the bloodstream, they can spread to other parts of the body and often cause arthritis, stiffness, and swelling. All of this adds to the global burden of disease.

To prevent the worst from happening, we are developing at least two new antibiotics for gonorrhea.

- The first is called gentamicin, but it is not an ideal choice. Gentamicin has side effects that affect the kidneys and hearing.

- The second is meropenem, which belongs to the same class as ceftriaxone. The downside of this drug is that if gonorrhea is resistant to ceftriaxone, it can also easily develop resistance to meropenem.

A Phase II clinical trial of a vaccine against Neisseria gonorrhoeae is also underway at the University of Oxford. However, the challenge with the vaccine is that humans do not develop long-lasting immunity to gonorrhea.

Therefore, while we do not yet have a new antibiotic to combat gonorrhea, the best way to deal with it is to prevent it from the start.

WHO recommends measures including: Abstaining from sexual contact with individuals infected with gonorrhea, using condoms and safe sex practices, avoiding sharing personal items such as towels, basins, underwear, and ensuring regular reproductive health check-ups.

Now more than ever, we need to be vigilant against gonorrhea, lest we have to resurrect medieval syringes, and doctors must relearn how to use them for infections that no longer have a cure.