When Tsar Nicholas II (the last Tsar in Russian history) attended church services, he often dropped 5 ruble coins bearing his own portrait into the charity cup, just like other parishioners.

At that time, 5 rubles was considered a generous donation—it could represent a month’s salary for a servant or half a month’s pay for a factory worker. However, what is surprising is that this money was not entirely his own, and he was also “not permitted” to use it as he wished.

In the book “Tsar’s Money: Income and Expenses of the House of Romanovs”, historian Igor Zimin states that to obtain these 5 ruble coins or any other funds, the Tsar had to write short notes to the office of Empress Alexandra Fyodorovna—the financial manager of the royal family—requesting, for example, “Send me 3,000 rubles and two 5 ruble coins” or “Send me an additional 2 gold coins.”

This indicates that the Russian Tsar did not actually have unlimited access to the national treasury.

Unable to “earn a living” due to high status

Before Tsar Paul I (1754-1801) ascended the throne, heads of state could use the national treasury for personal purposes. This was also considered one of the reasons why Empress Catherine II left a national debt of 200 million rubles upon her death (three times the annual budget of the Russian Empire at that time).

Tsar Paul I (the son of Empress Catherine II) and Empress Maria Fyodorovna had a total of 10 children. The burden of their social status prevented members of the Romanov dynasty from working or running businesses independently, yet they still needed to maintain good financial standing to uphold the royal family’s reputation, which compelled the state to allocate funds for their expenses.

Moreover, the financial stability of members of the lower house was essential to maintain the Romanov dynasty’s prestige among European royalty.

At this point, Tsar Paul I understood that if he did not limit the use of the family’s national reserve funds, there would be a risk of depleting the treasury. Therefore, in 1797, Paul I issued a decree establishing an annual allowance for royal family members.

What is the annual allowance?

Tsar Paul I created a complex hierarchy of allowances for each member based on their relationship to the king. The allowance for the head of state was not specifically defined, while the allowance for the Empress was set at 600,000 rubles (approximately 156 million VND at current exchange rates—120 times the annual salary of a state minister at that time).

The family of Tsar Paul I.

The children of the Tsar would receive an allowance of 100,000 rubles (27 million VND at current exchange rates) until they turned 20. After reaching the age of 20, their allowance would decrease to 50,000 rubles per year (approximately 14 million VND at current exchange rates).

The heir to the throne would receive 300,000 rubles (approximately 82 million VND at current exchange rates), and the wife would receive 150,000 rubles (approximately 41 million VND at current exchange rates). The Tsar’s grandchildren would receive 50,000 rubles until they turned 20, after which they would receive 150,000 rubles, with granddaughters receiving their allowance until marriage.

The building of the Ministry of the Imperial Household and Property in St. Petersburg.

Paul I’s decree anticipated the financial future of the next five generations of the royal family, and the increasing number of descendants would create a greater burden on the treasury. By the reign of Tsar Alexander III (1885), he had reduced the allowance amounts to less than a third, yet this was still considered a substantial sum compared to the living standards of the Russian people at that time.

Tsar Alexander III of Russia with his family, photo taken in 1886.

What was the Romanov dynasty allowed to purchase?

In their own country, royal family members could not shop freely due to the need for special security measures. If recognized, a shopping trip could turn into a public encounter.

This is also why Tsars, Grand Dukes, and their family members preferred to shop during visits to Europe. Nicholas II’s sister, Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna, once wrote about a trip to Copenhagen (the capital of Denmark): “I will never forget the thrill of being able to walk down the street, staring into shop windows, and buying anything I liked for the first time in my life.”

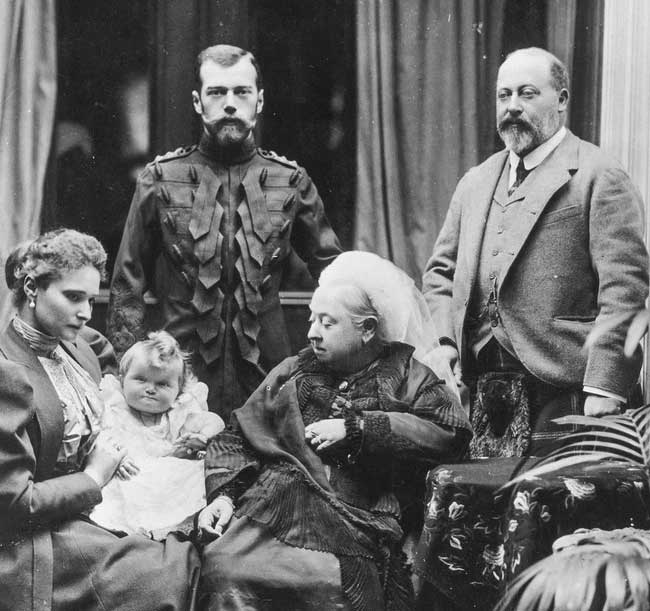

Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom and her son, Prince Edward VII, posed for a photograph with Tsar Nicholas II and his wife Alexandra, along with their newborn daughter, Olga.

Tsar Nicholas II himself also engaged in similar behavior. Anna Vyrubova, a close attendant of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, revealed that the Tsar “took everything he liked without asking about the price, as the state would cover all expenses, so he had no concept of money.”

However, obtaining a “huge” sum from the royal family was not easy for shopkeepers. They needed to send purchase invoices to the office of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna for approval, after which the Ministry of Finance would transfer the corresponding amount to the consulates of the respective countries, and only then would the payment go to the vendors. In the 19th century, when electronic payments did not exist, this process could take months.

So, what did the Russian Tsar often buy? Historian Igor Zimin shares that Tsar Nicholas I (1796-1855) often bought gifts for his family such as hats, bracelets, or silk stockings. However, the Tsar would not select these items himself; instead, an experienced maid would accompany him to assist, someone who truly understood the Empress’s tastes.

The chapel in Darmstadt (Germany) – the birthplace of Empress Alexandra Fyodorovna.

In fact, most Tsars and royal family members engaged in more charitable acts than shopping. For instance, in 1898, Tsar Nicholas II personally spent 500,000 rubles to assist families affected by famine, and he also allocated another 500,000 rubles for the construction of the chapel in Darmstadt (Germany) – the birthplace of Empress Alexandra Fyodorovna.