The Moon and Mars do not satisfy China’s ambition for space exploration. The Asian nation is targeting other star systems in its quest for exoplanets (a term referring to planets outside our Solar System). This month, Chinese scientists will unveil detailed plans for their first exoplanet search mission.

The Chinese astronomy sector aims to find a planet similar to Earth orbiting a Sun-like star. For a long time, scientists have believed that such a planet could be referred to as Earth 2.0, as it may contain liquid water and even support life.

Chinese astronomy aims to find a planet similar to Earth.

Within the Milky Way, NASA’s telescopes have discovered over 5,000 exoplanets of various sizes. Some of these are rocky planets akin to Earth, orbiting stars of diverse ages and sizes. However, none have yet earned the title of “Earth 2.0.”

With current technology, it is challenging to detect signals from Earth-like planets, especially when the central star emits immense gravitational force and bright light in a region of space. This is the assessment of Jessie Christiansen, an astrophysicist at NASA’s Exoplanet Science Institute.

Named “Earth 2.0,” the mission aims to identify the most suitable planet for this still-nascent concept. The Chinese Academy of Sciences will be the primary funding organization for the project, and they are currently finalizing the preliminary design phase. If the satellite design is approved by an expert panel in June, the Academy will immediately allocate funds to initiate the installation phase.

If all goes well, the Chinese will launch this exploratory satellite on a Long March rocket before the end of 2026.

A Suite of Seven Lenses

The Earth 2.0 satellite will feature seven telescopes and will observe the sky for four years. Six of the telescopes will focus on the Cygnus-Lyra constellation, which is also the area being monitored by NASA’s Kepler telescope.

“The Kepler field is an accessible target, and we can obtain orbital data from it,” said Ge Jian, the astronomer leading the Earth 2.0 project, during a press briefing.

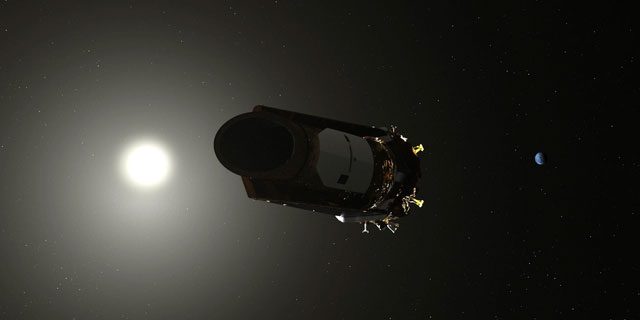

Illustration of NASA’s Kepler telescope in space.

The six telescopes will search for exoplanets by observing changes in the brightness of a star, which indicates that a planet is transiting in front of its central star. With multiple lenses, the Earth 2.0 satellite will have a much broader observational range than Kepler, covering an area five times larger and capable of observing up to 1.2 million stars.

“Considering our sky survey capabilities, our satellite could be about 10-15 times more powerful than NASA’s Kepler telescope,” researcher Ge Jian stated.

The seventh lens of Earth 2.0 is an intriguing telescope with a microscopic lens, designed to observe rogue planets that are not influenced by the gravitational field of any star. This lens will focus on the region near the center of the Milky Way, where a large number of stars are concentrated. According to expert Ge Jian, if launched, Earth 2.0 will be the first space device equipped with a microscopic lens telescope.

“Essentially, our satellite can calculate measurements to determine the size, mass, and lifespan of exoplanets. The mission will yield a large collection of exoplanets for future research,” the Chinese astronomer affirmed.

Doubling the Data: What for?

NASA launched Kepler into space in 2009, hoping to determine the density of Earth-like planets in the Milky Way. To confirm an exoplanet as “Earth-like,” experts must measure the time it takes for the planet to complete an orbit around its central star (which is approximately one Earth year). Scientists estimate that at least three complete orbits are needed to find the accurate orbit, equivalent to data collected over three years. If there are gaps in the data, the research process will take even longer.

However, just four years into the Kepler mission, part of the equipment malfunctioned, leading to data gaps. With Earth 2.0, astronomers will have access to a massive amount of additional data, which can be combined with what Kepler has already collected to identify Earth-like exoplanets.

China’s Long March rocket.

Researcher Ge Jian plans to announce the observation results within one to two years after Earth 2.0 completes its mission. “There will be a lot of data, so we need as much assistance as possible,” he said. The current research team has grown to 300 members, including scientists and engineers, most of whom are from China. However, Ge Jian hopes that global experts will join the effort. “Earth 2.0 is a fantastic opportunity for international collaboration.”

Currently, the European Space Agency (ESA) is also planning a mission to search for exoplanets. Named Planetary Transits and Oscillations of Stars (PLATO), the exploratory satellite is expected to launch in 2026.

PLATO will feature 26 telescopes, allowing it to observe a much larger area than Earth 2.0. Every two years, European experts will change PLATO’s viewing direction to expand the range of exoplanet searches.