Scientists around the world have discovered methods to help humanity escape the threat of extinction due to pandemics.

1. Edward Jenner

Edward Jenner – The pioneer of vaccination.

Louis Pasteur is recognized globally as the father of vaccines. However, the reality is that the first foundation for vaccination was laid by Edward Jenner – a distinguished physician of the Royal Society in London, England. The history of world medicine acknowledges

Edward Jenner’s significant contributions in establishing a “vaccination empire” that protects billions of people. In 1796, a smallpox pandemic erupted in Europe. At that time, no scientist had any concept of viruses. In 1798, Dr. Edward Jenner announced the results of his experiments that laid the groundwork for vaccination.

Smallpox has been present throughout human history, becoming a pandemic since the 6th century, originating in Africa and later spreading to Europe and Asia. In the 17th and 18th centuries, smallpox claimed millions of lives. The disease was caused by a virus, but doctors living before Louis Pasteur had no understanding of this. They believed it to be an incurable disease.

It is estimated that in 1773, for every 10 English people infected with smallpox, 9 died. Survivors were left with scars, pockmarked faces, and suffered from lifelong isolation and shame. They were even shunned and ostracized by their communities.

The initial symptoms of smallpox included the emergence of red spots, which then developed into blisters all over the body, causing fever, infections, and potentially leading to blindness and death. The disease spread through respiratory droplets and contact, leading to a rapid increase in cases. Dr. Jenner dedicated many years to studying this disease but could not find a cure.

One day, Jenner accidentally discovered a disease called “cowpox”, which is smallpox in cows. He noticed that those who milked cows after contracting cowpox did not get smallpox. This led Dr. Jenner to question: “Could cowpox be transmitted to humans to prevent smallpox? This way, people would contract a non-lethal disease and escape the deadly smallpox.”

Jenner approached a woman who was milking cows and had cowpox. This disease frequently appeared in cows, causing them to develop blisters all over their bodies. The doctor extracted fluid from the cowpox lesions on the arm of a cowherd named Sarah Nelmes. He then inoculated this fluid into the arm of a healthy 8-year-old boy from the same village named James Phipps.

The boy showed symptoms of cowpox. 48 days later, Phipps recovered from cowpox. Dr. Jenner then inoculated him with smallpox material. A strange phenomenon occurred: Phipps did not contract smallpox.

Subsequently, Dr. Jenner applied this method to his own son, who was only 10 months old. The result was that the baby also did not contract smallpox. Based on this principle, the doctor completed the technology for creating vaccines with the steps: extracting the smallpox virus from an infected cow; weakening the virus; and injecting these weakened viruses into the human body through the bloodstream. Dr. Jenner explained that those vaccinated would not contract smallpox because their blood contained an immunity factor.

In 1798, Jenner’s vaccination method was disseminated worldwide. Two years later, the British government invited him to vaccinate the Royal Navy. Emperor Napoleon in France also ordered all soldiers to be vaccinated against smallpox. Subsequently, the United States adopted this method as well.

In 1802, Dr. Jenner was elected President of the International Committee for Smallpox Prevention. He received numerous awards from Queen Victoria of England, the Tsar of Russia, the Emperor of France, and the President of the United States for his significant contributions to humanity. Later, Jenner was invited to work at the French Academy of Sciences. In powerful nations such as England, France, and Italy, statues of him were erected to honor and remember his contributions.

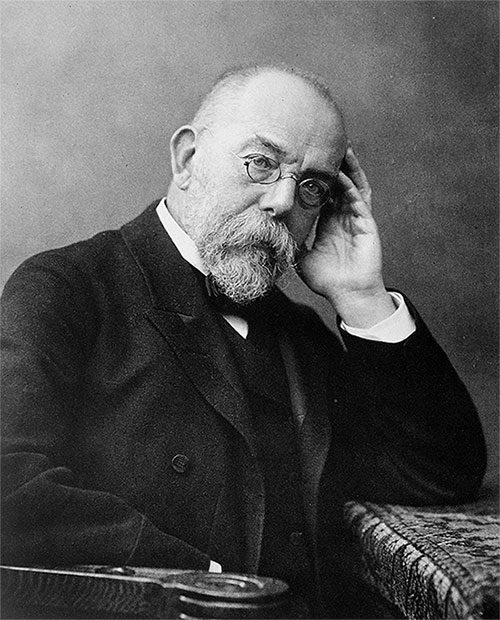

2. Robert Koch

Dr. Robert Koch.

Robert Koch was a German physician who helped establish bacteriology as a scientific discipline. Koch made significant discoveries in identifying the bacteria that cause anthrax, cholera, and tuberculosis.

When Robert Koch was appointed as a health official in Wollstein, he began investigating a pressing health issue – anthrax. Koch designed a study using mice, guinea pigs, rabbits, dogs, frogs, and birds.

He discovered that when he transfused the blood of a sheep that had died from anthrax into a mouse, the mouse also died a few days later. Upon autopsy, he found whip-like structures in the blood, lymph nodes, and spleen. He injected blood from the spleen of the dead mouse into another mouse and got the same results. This phenomenon repeated over dozens of generations.

Koch hypothesized that these “whips” were living bacteria, spreading by elongating, constricting, and then splitting in two. This bacteria-rich blood lost its ability to cause disease after a few days. Therefore, this could not explain the prolonged toxicity of the soil source.

Koch developed artificial culturing techniques, allowing him to observe the changes in bacteria over time. He found that aqueous humor was a suitable culture medium. After injecting a solution containing bacteria into the cornea of a rabbit, the aqueous humor in their eyes became cloudy.

He also developed new microscopy observation techniques. By placing a small sample of infected spleen tissue into a drop of aqueous humor on a concave slide, he was able to observe the bacteria proliferating for several days. He could adjust the temperature, humidity, and ventilation for the samples using oil lamps, humid chambers, incubators, and vegetable oil.

He discovered that under optimal conditions – warm, humid, and ventilated, bacteria would enlarge, elongate, and filament. On these filaments, large nodules gradually formed into spheres and persisted even after the filaments disappeared. When the culture medium dried and was supplemented with aqueous humor, the bacteria emerged from the spheres.

Koch hypothesized that these spheres were spores, formed under harsh conditions. Based on his new understanding of the role of spores in disease causation, Koch recommended that infected livestock be burned or buried in cold ground to prevent spore formation.

After years of diligent research on animals and even on humans with tuberculosis, Robert Koch finally discovered the cause of the disease. It was a type of bacterium (later named after him) measuring 1 – 4 micrometers, capable of resisting both acid and alcohol.

Koch found the bacterium in the sputum and lung cavities of patients. He infected a healthy animal by injecting them with infected sputum. He concluded that sputum was the primary source of infection, and patients with laryngeal or pulmonary tuberculosis spread large amounts of bacteria.

Although it could not multiply outside the host, the tuberculosis bacillus in dry sputum could retain its infectious ability for weeks. Therefore, properly handling patients’ sputum and disinfecting the environment was an effective way to prevent the disease.

On March 24, 1882, Koch presented his findings on tuberculosis at a meeting of the Berlin Physiological Society. This was one of the most influential presentations in the history of medicine. In August 1883, Koch and his colleagues traveled to Egypt, where a cholera epidemic was raging around the port of Alexandria. After months of investigation, he finally discovered the cause of cholera: a comma-shaped bacterium.

3. Pearl Kendrick and Grace Eldering

These two scientists discovered a treatment for whooping cough.

Microbiologists Pearl Kendrick and Grace Eldering discovered a treatment for whooping cough. Although this disease is not new to many parents today, in the 1930s, it “terrorized” the lives of many families.

Diagnosing whooping cough was also challenging if relying solely on symptoms. By the mid-20th century, whooping cough remained an unstoppable disease. It was so dangerous that a child with the disease could infect half a classroom and all siblings at home. In the early 1930s, whooping cough was responsible for the deaths of 7,500 American children each year. Those who survived sometimes suffered permanent physical and cognitive damage.

All of this changed thanks to Kendrick and Eldering. Their work involved daily testing of medical and environmental samples. However, studying whooping cough became their passion.

Initially, their main goal in researching whooping cough was to diagnose the disease more quickly and accurately. This way, patients could be isolated as soon as possible. Their chosen “weapon” was the cough plate, essentially a petri dish – a cylindrical dish with a lid – containing a microbial culture medium underneath.

Kendrick, Eldering, along with doctors, nurses, and other team members held the petri dish for patients to cough into. The petri dish was then covered and sent to the laboratory to culture the bacteria into suitable clusters for analysis.

They quickly expanded their research throughout the city to monitor and control whooping cough. Instead of using human blood as a culture medium, they switched to sheep blood, as it was cheaper and more readily available.

In January 1933, Kendrick and Eldering created the first experimental vaccine.

The vaccine consisted of inactivated whooping cough bacteria, which were cleaned, sterilized, and suspended in saline solution.

Scientists who previously developed vaccines often overlooked crucial information regarding preparation, dosage, and other factors. This led to potentially variable results. Kendrick and Eldering, however, applied a more systematic approach at every step, from the initial collection of bacteria to testing whether the vaccine actually protected children.

They found that bacteria collected at a certain stage were more likely to elicit a stronger immune response. The two scientists conducted multiple tests of the vaccine. They ensured the vaccine’s safety by administering it to laboratory animals and themselves.