Dogs Were Once Terrifying Living Weapons, At Least for 3,000 Years of History.

In the 16th century, just one Becerrillo and 10 Spanish soldiers were enough to tear apart the defensive lines of hundreds of Native American warriors, crushing resistance through unparalleled fear.

From Hunting Dogs to War Dogs

For centuries before Christ, dogs were fierce battle animals.

We are accustomed to the notion that dogs are humanity’s most loyal friends. According to archaeological discoveries, humans successfully domesticated and lived alongside these animals over 50,000 years ago. They helped guard homes, protect livestock and food supplies, assisted in hunting, and simply served as pets.

For thousands of years, dogs accompanied humans, serving as the best animal companions and protectors. Around 600 BC, Emperor Alyattes (620 – 560 BC) of Turkey initiated the training of war dogs for military purposes. He used trained dogs to attack humans and protect the homeland from the invading Cimmerians.

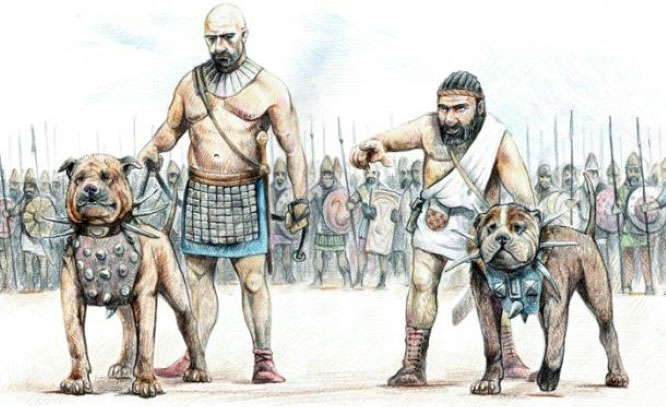

Following Alyattes, the training and use of war dogs spread everywhere. In Asia Minor, soldiers combined war dogs with cavalry. Horsemen galloped forward with war dogs, charging directly into enemy lines and releasing them to attack from all sides.

In 480 BC, during the invasion of Greece (Southern Europe), Emperor Xerxes I (519 – 466 BC) of Persia (Middle East) brought along many packs of Indian hunting dogs. Many centuries later, the Roman army imitated and expanded this tactic, forming large war dog units with breeds like Canis Molossus and Molossian. They even selectively bred fierce dog breeds specifically for battle.

In 55 BC, General Julius Caesar (100 – 44 BC) of Greece eyed the shores of the Kingdom of Britain. At that time, Celtic warriors led fierce, battle-ready Mastiff dogs on patrol, boldly challenging Caesar and preventing his ships from landing.

Living Weapons

Becerrillo was the most aggressive war dog of the Spanish colonists.

In 1492, Christopher Columbus (1451 – 1506, Spain) discovered America. In 1493, Columbus unleashed war dogs to attack the Native American tribes residing on the island of Hispaniola (North America). In 1494, he continued using war dogs to breach the defensive lines of the Native Americans blocking his entry into Jamaica (Caribbean).

On March 27, 1495, Columbus and his brother Bartholomew led a Spanish expeditionary force of 200 soldiers, 20 cavalry, and 20 Mastiff war dogs to Hispaniola. The operation was commanded by Alonso de Ojeda (1468 – 1515), a master dog handler.

Before being assigned to conquer Hispaniola, Ojeda had achieved numerous victories in his homeland of Granada. Thanks to him, the Spanish crown crushed the resistance of the minority Moors.

In Hispaniola, Ojeda fully utilized his experience with war dogs from Granada. He positioned them on the far right flank and waited for the battle to reach its peak before unleashing the dogs.

Stimulated by the atmosphere of anger, the pack of war dogs furiously targeted the fiercely engaged Native American warriors, pouncing on their bare bodies, pinning them down, and biting and tearing at them.

In the 16th century, America was drenched in the blood of Native Americans. Notorious conquerors like Balboa, Velasquez, Cortes, De Soto, Toledo, Coronado, and Pizarro all brought war dogs with them, each expedition including hundreds, even thousands, of them.

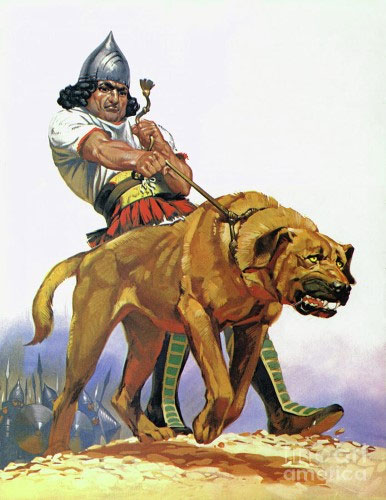

Initially, the most favored war dog by the Spanish was the Mastiff, a hunting breed weighing over 100 pounds, with jaws powerful enough to crush bones. Later, they became increasingly enamored with the Becerrillo – a large, fierce Bull dog with a fiery coat and an extremely aggressive demeanor.

Spanish history holds that the first Becerrillo was the dog of Ponce de León (1474 – 1521). León participated in the conquest of Puerto Rico (Caribbean), and through bribery of Diego (Columbus’s son), he secured the governorship of the island. He trained his Becerrillo to distinguish between Spaniards and natives, later using it to hunt down Native American warriors.

Becerrillo was notorious for its tracking skills, pursuit, and psychological terror against the indigenous people of America. Historian Bartolomé de las Casas (1484 – 1566) noted, “Becerrillo attacked the enemy in a frenzy and defended its friends with the utmost bravery.” He also stated, “The natives feared 10 Spanish soldiers with one Becerrillo more than a large army of hundreds.”

In 1512, Diego “overthrew” León. Losing his position and opportunity for plunder, León decided to set sail toward the island of Bimini, rumored to be filled with gold and treasures. He entrusted the pack of Becerrillo to Guilarte de Salazar and Sancho de Aragón for management. One night, Salazar discovered an attacker at the soldiers’ camp. In just 30 minutes, he commanded the pack of Becerrillo to eliminate 33 indigenous warriors.

A Tragic End

While waiting for the new governor to be appointed, Salazar camped outside the Caparra settlement in Puerto Rico. Bored, he folded a piece of paper and gave it to an old woman, instructing her to take it to the new governor. As the woman set off, he secretly brought Becerrillo along and suddenly ordered it to charge and kill her.

Before the large, ferocious dog, the old woman collapsed, kneeling down. She clasped her hands, crying and pleading with the dog to spare her. Miraculously, Becerrillo stopped. It sniffed gently as if to comfort the old woman, then turned and walked away, ignoring Salazar’s shouts. Upon learning of this, the new governor immediately prohibited any acts of terror against the people.

In 1514, the Carib (indigenous people of Vieques Island) revolted, capturing Sancho de Aragón. In the battle, they attacked and retreated strategically using dugout canoes. The Spanish colonists, accustomed to relying on Becerrillo, faced their greatest difficulties. The war dogs could do nothing against the enemy on the water and became giant targets. One by one, they fell under a rain of arrows, dying in agony.

If Becerrillo was a terror to the enemies, it was the most beloved companion to the Spanish soldiers. Despite being covered in wounds, it shielded and protected its owner until the very last moment. Nothing was more heartbreaking than its dying moments. The Spanish soldier mourned Becerrillo as much as a comrade, silently burying it and remembering it forever.

The defeat of Becerrillo in 1514 also marked the end of the era of war dogs.