Will Climate Change Affect Human Evolution?

Since the 1920s, scientists have suspected that climate change may have played a significant role in the evolution of humanity. At that time, some researchers believed that a drier environment could have prompted early humans to start walking on two legs to adapt to life on the savannah. However, this perspective is difficult to prove due to the limited amount of representative fossil data available at the time.

A new study published in the journal Nature has employed an unprecedented circulation model to simulate Earth’s climate over the past 2 million years. Specifically, this research examines how long-term climate fluctuations, driven by Earth’s astronomical movements, created environmental conditions that influenced human evolution.

As our planet is pushed and pulled by other planets, its tilt and orbital shape also change, affecting Earth’s climate. For instance, Earth’s tilt oscillates in a 41,000-year cycle, impacting the intensity of seasons and rainfall in tropical regions; over a cycle of more than 100,000 years, Earth transitions from a rounder orbit to a more elliptical one, with the rounder orbit providing more sunlight and longer summers, while the elliptical orbit reduces sunlight, potentially leading to glacial periods.

Simulations indicate that temperature and other planetary conditions have affected early human migrations and may have contributed to the emergence of modern humans around 300,000 years ago. The results provide clear evidence supporting the claim that climate change is related to the evolution of humanity.

Temperature and other planetary conditions have influenced early human migrations.

The Emergence of Homo sapiens in Simulated Conditions

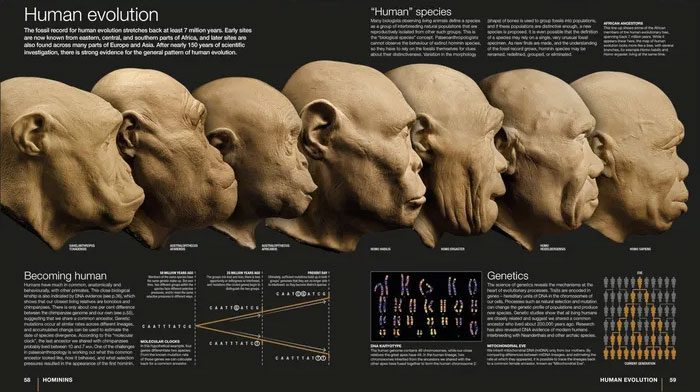

Using supercomputers, researchers ran a simulation that combined these astronomical changes, recreating how temperature and rainfall could have affected human availability over millions of years. By integrating these simulations with thousands of fossil records and other archaeological evidence, they calculated all the locations and times at which six human species, including Homo ergaster and Homo habilis, appeared in the model.

Although these different hominin species preferred various climatic environments, their habitats reacted to climate changes caused by the astronomical shifts in Earth’s axial tilt and orbital eccentricity. To examine the relationship between climate change and human habitats, researchers shuffled the ages of the fossils.

The habitats of prehistoric human groups reacted to climate-induced changes.

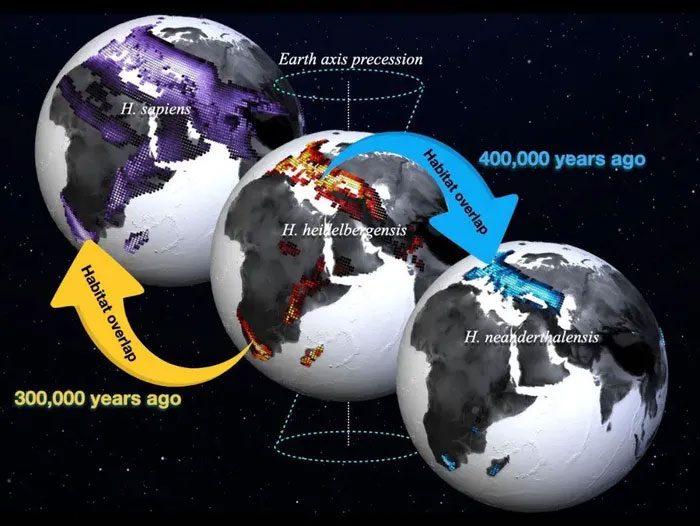

By analyzing the vast amount of data generated from the simulations, researchers found that the three most recent hominin groups, Homo sapiens, Neanderthals, and Heidelbergers, exhibited significantly different habitat patterns. This suggests that, for at least the past 500,000 years, the actual order of climate change has played a crucial role in determining where different hominin groups lived and where their remains were found.

Next, researchers posed the question of whether the habitats of different human species overlapped spatially and temporally. They examined data from five major hominin groups and discovered that early African hominins, from about 2 million to 1 million years ago, preferred stable climatic conditions, restricting them to relatively narrow living areas. After a major climate change event around 800,000 years ago, Heidelbergers adapted to a wider variety of food sources, allowing them to become “global wanderers” to remote regions of Europe and East Asia.

We have successfully adapted over thousands of years to slow past climate changes.

Previously, some scientists suggested that Homo Heidelbergensis may have given rise to multiple species globally, including Neanderthals in Eurasia and Homo sapiens somewhere in Africa. The new model suggests that the global distribution of Heidelbergers was possible because a more elliptical orbit created wetter climatic conditions that allowed Heidelbergers to migrate more widely.

From the simulation results, Homo Heidelbergensis began expanding their habitat about 700,000 years ago, while Neanderthals and Denisovans may have branched off from the Eurasian lineage of Heidelbergers around 500,000 to 400,000 years ago. This closely aligns with recent estimates derived from genetic data or analyses of morphological differences in human fossils.

New Methods, New Insights

These results were achieved using the Aleph supercomputer. Aleph ran continuously for six months, completing the longest and most comprehensive climate simulation to date. The outcomes from these simulations could provide new insights into the locations and mechanisms of human emergence.

There are still many debated issues in paleontology, and while these new results are unlikely to settle those debates, this study clearly demonstrates that validated climate models are highly valuable in addressing fundamental questions about human origins. Researchers believe that the paleontology community should more fully exploit the potential of continuous paleobiological simulations.

The new study provides evidence that climate plays a significant role in human evolution, indicating that we have successfully adapted over thousands of years to slow past climate changes. Of course, we still need more evidence showing how astronomical cycles influenced the orbits of our human ancestors. Next, researchers plan to run larger models that integrate genetic data.