The gravity hole in the Indian Ocean is an area where the Earth’s mass decreases, resulting in weaker gravitational forces and lower sea levels than average, leaving scientists puzzled.

Deep beneath the Indian Ocean lies a massive gravity hole covering approximately 3 million km², which has confounded scientists for decades. Technically, this is not a hole in the traditional sense. However, geophysicists use this term to refer to a region where the gravitational pull is significantly lower than average.

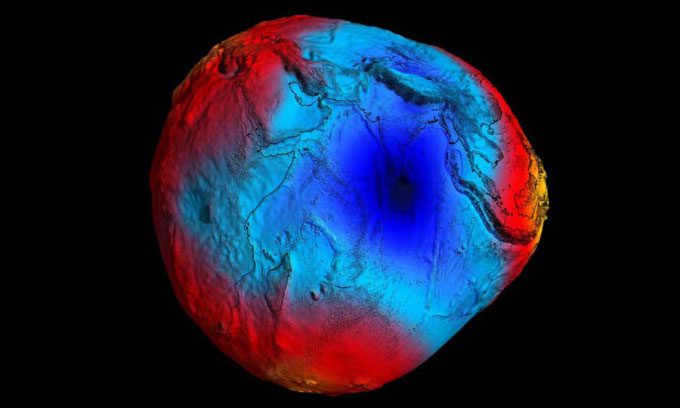

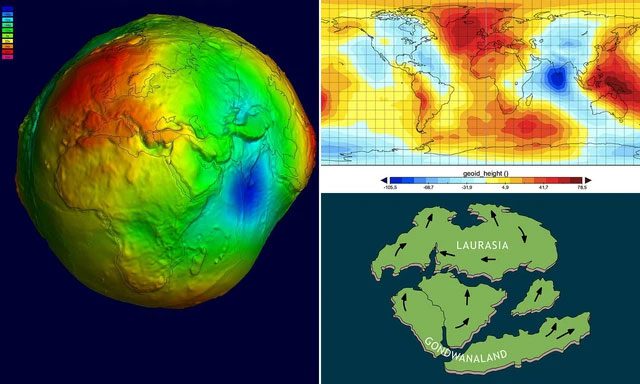

Map showing areas of weak (green) and strong (red) gravity on Earth. (Image: ESA/HPF/DLR).

The Earth is not a perfect sphere; the poles are flattened while certain areas bulge along the equator, causing gravity to vary depending on location. Scientists have mapped these effects to create the “geoid” of the Earth—a potato-shaped map that visually represents these gravity valleys and depressions.

If you look at the Earth’s gravitational map, you will notice a gigantic green spot south of India, known as the Indian Ocean Gravity Low (IOGL), which is the largest gravitational anomaly on our planet and has attracted researchers’ attention since its discovery in 1948.

This is the largest gravitational anomaly on our planet.

|

Gravitational anomaly is the difference between the actual gravity measured at a location and the theoretical gravity expected for a perfectly spherical and smooth Earth. However, the Earth’s gravitational pull is not completely uniform, and variations in mass distribution beneath the surface cause fluctuations in gravitational forces. Gravitational anomalies can be caused by changes in the density and thickness of the crust, mantle, and core of the Earth. These anomalies affect the shape of the ocean’s surface, creating a non-uniform surface that follows the contours of the Earth’s gravitational field. This shape is referred to as the Geoid, which represents what we would see if all influences of tides, winds, and ocean currents were removed. The Geoid is often visualized as a potato-like shape, with bumps corresponding to regions of high and low gravity. |

In a recent study published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, geologist Attreyee Ghosh and research fellow Debanjan Pal from the Indian Institute of Science examined the IOGL and discovered that the surrounding ocean’s sea level is nearly 107 meters lower than the global average, as reported by Futurism on July 1.

After running multiple computer models on the area’s changes over the past 140 million years, the research team concluded that the IOGL may result from the “African blob”—a massive mass in the Earth’s mantle located over 965 km deep beneath Africa—being pushed down beneath the Indian Ocean.

Geologists believe that this mass formed from the remnants of the ancient Tethys Ocean, which existed between the two supercontinents Laurasia and Gondwana over 200 million years ago. Then, about 120 million years ago, the Indian Ocean formed as Gondwana moved northward, encroaching into the ancient ocean.

About 20 million years ago, fragments settled in the lowest part of the mantle, replacing high-density material originating from the “African blob”, a solidified magma bubble that is 100 times taller than Mount Everest and trapped beneath Africa. Low-density magma columns rose to replace the dense material, reducing the overall mass of the area and weakening its gravitational pull.

Scientists have yet to confirm the predictions from the model using seismic data to verify the existence of low-density magma columns beneath the hole. Meanwhile, researchers have noticed that Earth’s magma is filled with strange masses, some of which appear and disappear unpredictably.

According to Pal and Ghosh, the IOGL may have taken its current shape around 20 million years ago, when hot, viscous magma flows surrounded the area as pieces of the Tethys Ocean sank into the Earth’s mantle.

However, Himangshu Paul, an expert at the National Geophysical Research Institute of India, suggests that there may still be other factors behind the existence of the IOGL. “Simulations may not accurately replicate nature,” he notes.