Vodka, jet fuel, hand sanitizer, perfume… An increasing number of companies are looking to transform carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions captured from the air or factory smoke into everyday consumer products. By doing so, greenhouse gases will not escape into the atmosphere and contribute to global warming – or at least they will be recycled a few times before being emitted again.

Carbon capture technology works by separating CO₂ from other gases using expensive solvents. These solvents are capable of attracting individual CO2 molecules from the air, much like iron filings are drawn to a magnet.

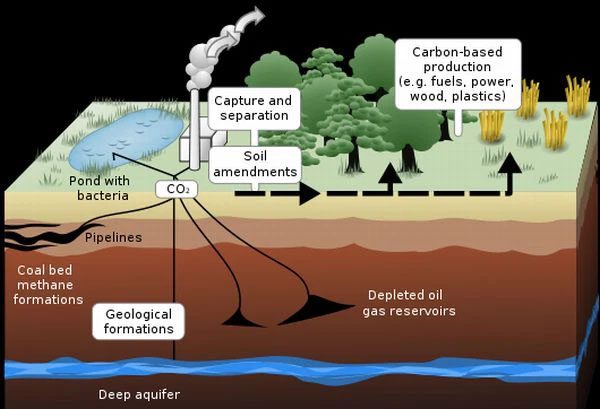

Once captured, CO₂ is buried underground. How can a gas be buried underground, you ask? By utilizing the very oil wells that we have depleted, pumping CO2 into empty gas reservoirs and sealing them off.

Once captured, CO₂ is buried underground.

The idea sounds great, but unfortunately, it is often not feasible in practice. This is because the cost of separating CO2 using solvents is very high. Furthermore, companies must also solve the transportation of CO₂ and find suitable geological structures to store it. So why go through all that trouble when building a smokestack would be cheaper and easier?

Unfortunately, scientists have realized that if we continue to build smokestacks indiscriminately, the Earth will heat up due to an atmosphere filled with greenhouse gases. Even politicians have recognized this as a threat.

They have come together to agree on treaties, standards, and regulations to limit global emissions. This has spurred the formation of a green economy, helping humanity gradually abandon industrial practices that harm the very environment we live in on Earth.

Recycling CO2 into alcohol, plastics, building materials, and aviation fuel

Alongside this transformation, ideas for a circular green economy with carbon have also emerged. Notably, several startups are pursuing the idea of “carbon capture and utilization” (CCU), believing that CO₂ can be used to produce goods, with the sale of these goods funding the scaling of their technology.

For example, Air Company, based in Brooklyn, USA, claims to have created a type of “the most sustainable alcohol in the world” by mixing captured CO₂ with hydrogen derived from water and wind energy. Their high-proof alcohol can be processed into various consumer goods, including vodka starting at $65 a bottle.

Vodka made from greenhouse gas emissions.

“Using the same amount of land, our technology can absorb 100 times the CO₂ rate of a well-managed forest,” said Gregory Constantine, co-founder of Air Company.

Adaptavate, a startup in the UK, has taken a different approach. They use agricultural waste and lime-based binders to capture CO₂ and then create gypsum walls.

If their product sees widespread use, it could significantly reduce emissions from the construction sector, which is responsible for 38% of global energy-related emissions.

Another notable example is Econic Technologies, a spin-off from Imperial College London founded in 2012. They currently hold technology for manufacturing polymers from CO2, which serves as a basis for producing a range of consumer and industrial products derived from petroleum, such as plastics.

According to CEO Keith Wiggins, their process uses a licensed catalyst that can replace up to 50% of traditional petroleum feedstock.

The company aims to replace polyurethane, a type of polymer used to create foam found in insulation materials, mattresses, and refrigerators, with recycled CO2 coatings and adhesives.

They have recently announced a partnership with Manali Petrochemicals, a major manufacturer in India. The company claims that if all polyurethane worldwide were produced using their technology, we could reduce emissions by over 11 million tons of CO₂ annually.

According to the non-profit organization Carbon180, a potential market worth $1 trillion is forming in the United States alone for products made from captured CO₂ emissions. These products range from plastics and building materials to food and beverages.

One alternative product expected to make a significant difference in the effort to achieve global net-zero emissions is aviation fuel, as we currently have no means to produce it sustainably.

Currently, Dimensional Energy, an energy company, is trying to create usable fuel from waste carbon and sunlight. Their process works by adding water to captured carbon and heating the mixture to high temperatures using electricity generated from solar panels:

Scientists believe CO₂ can be used to produce goods.

Catalysts are introduced to combine carbon and hydrogen atoms from water into a compound that can be converted into fuel for cargo ships and passenger planes.

Dimensional Energy states that they plan to capture and utilize their first 500,000 tons of CO₂ by the end of this decade. This is an extremely ambitious goal compared to the largest operational carbon capture facility today, the Orca facility in Helsinki run by Climeworks AG, which can only capture 4,000 tons of CO₂ per year.

Substantial efficiency or just inflated promises?

The issue for companies like Dimensional is that CCU was born as a means to raise funds for carbon capture technologies. However, many governments and companies today have set goals to reduce emissions to zero, meaning they will prioritize CO₂ storage technologies such as burying it back underground over recycling it.

According to Howard Herzog, a senior research engineer at MIT’s Energy Initiative, capturing CO2 will be more effective than trying to recycle it. Converting CO2 into other products also requires energy, and we do not always have enough renewable energy to do so.

If you use fossil fuel energy to recycle CO2, that process creates new emissions. And even solar energy is not entirely clean if it is stored in batteries.

Capturing CO2 will be more effective than trying to recycle it.

Thus, while CO2 recycling technologies are proving to be an effective marketing tool, industry experts argue that the scenarios they propose are all fictional. It will never be possible to replace all polyurethane worldwide with recycled CO2 products.

Therefore, when it comes to promises of alcohol or hand sanitizer recycled from greenhouse gas emissions, in the best-case scenario, they will serve as an educational tool for investors about the benefits of carbon capture technology. In the worst-case scenario, it is merely a marketing gimmick that offers little benefit to the planet.

This reminds us of a study published in the journal Nature in 2017, where scientists were not very optimistic about the potential of CCU technologies. They estimated that even with enough clean energy to support large-scale CO₂ recycling, the actual contribution of this sector to the global net-zero target would still be negligible, at less than 1%.

“Reusing carbon is like a climate solution, but it does not permanently remove carbon from the atmosphere,” said Giana Amador, policy director at Carbon180. “Carbon capture or removal is not a license for fossil fuel companies to continue emitting.”