The remains of an adult, a teenager, and a small child that do not belong to our species have been uncovered in a cave in Serinyà Park.

Serinyà is a famous prehistoric cave park in Girona Province – Spain, where a recent survey revealed the teeth of 3 individuals that are not part of our species and lived tens of thousands of years apart.

According to Heritage Daily, the 3 teeth were discovered from sediments inside the Abreda Cave, part of the Reclau cave complex in Serinyà Park.

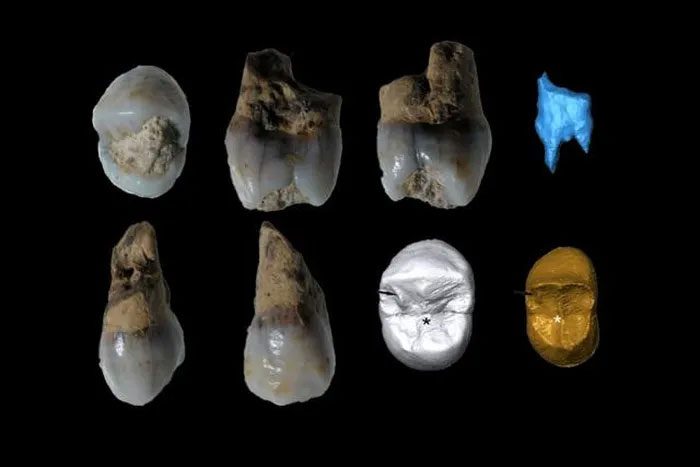

The teeth found in Abreda have been identified as belonging to 3 individuals that do not belong to our species – (Photo: IPHES-CERCA).

The Abreda Cave served as a shelter for Neanderthals, Homo sapiens, and many other animals, featuring 5 distinct cultural layers dating back to the Neolithic period: Solutrean, Upper Perigordian, Aurignacian, and Mousterian.

Homo sapiens refers to our species, while Neanderthals are a closely related species within the genus Homo, which became extinct over 30,000 years ago but left some DNA in modern humans through ancient interbreeding.

Archaeological evidence suggests that this cave was the first living site for Neanderthals from 140,000 to 39,000 years ago, followed by modern humans from 39,000 to 16,000 years ago.

In this new study, a team led by Dr. Marina Lozano from the Institute of Human Paleoecology and Social Evolution in Catalonia, part of the Tarragona Advanced Research Center (IPHES-CERCA – Spain), analyzed the 3 teeth collected from the Abreda cave.

The findings indicate that they all belong to Neanderthals, including an adult, a teenager, and a very young child.

Previous studies have shown that Neanderthal children developed teeth much earlier than our species.

Two of these teeth are estimated to be at least 120,000 years old, while the third dates from 71,000 to 44,000 years ago.

Dental remains are the type of fossils that paleoanthropologists always hope to find, as they provide not only genetic information but also insights into the diet of the individual.

Thus, Dr. Lozano believes that these new discoveries will help unlock new understandings of the survival strategies of the last Neanderthal groups in the Iberian Peninsula, at a time when coexistence with anatomically modern humans may have occurred.