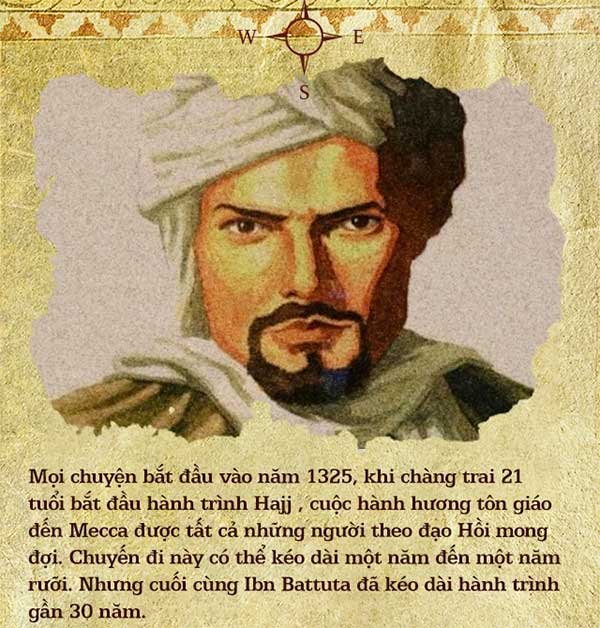

In 1325, at just 21 years old, Ibn Battuta embarked on a journey that was originally intended to last just over a year; however, everything turned out differently, and it extended to a remarkable 29 years.

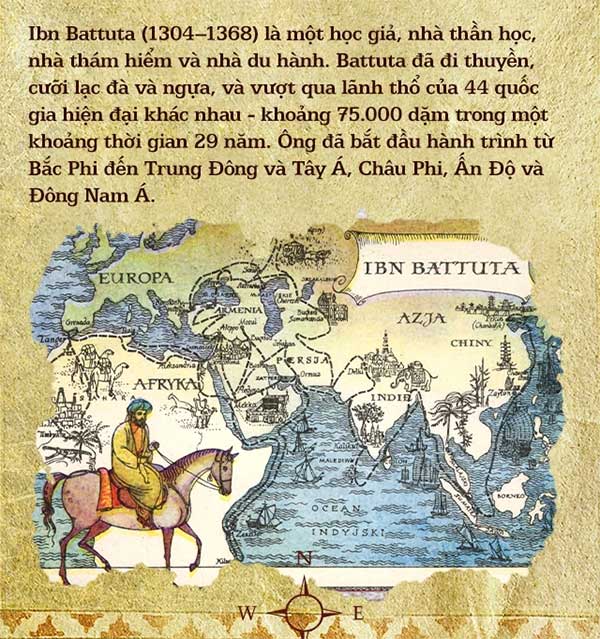

During this journey, many have likened Battuta to the Marco Polo of the Middle East. He adventured across 75,000 miles (over 120,000 km), which today constitutes the territory of about 44 countries. Throughout his travels, he encountered pirates and hunters, joined caravans of “mystics,” and compiled one of the most comprehensive works ever known about the 14th century, titled Rihla.

The Beginning of the Adventure

Ibn Battuta was born in February 1304 into a family of legal scholars in Tangier, Morocco. Following the customs of North Africa at that time, he likely studied at an Islamic legal center as a young man, where he would be encouraged to undertake the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, one of the largest pilgrimages in the world and the fifth pillar of Islam, a religious obligation that must be fulfilled at least once in the lifetime of a Muslim if they are able to do so.

This very encouragement led to a journey that would last nearly 30 years, although his initial plan was only for 16 months. While this is less mentioned in Rihla, Battuta’s descriptions of leaving for Hajj indicate that he attempted to spend more time with his family before embarking on the journey. He also expressed concern about being alone for much of the trip.

“I set out alone, with no caravan to join and no companion, but the urge filled me, and the long-held desire in my heart was to visit the sacred holy place,” Ibn Battuta wrote in his detailed account of his travels.

“Thus, I prepared, determined to leave my loved ones and my home like birds leaving their nests. With my parents, I still had responsibilities binding me in life, and it weighed heavily on me to part from them, causing both me and them to suffer from this sorrow of separation.”

Battuta’s Journey

Ibn Battuta’s journey began in Tangier on June 14, 1325. Initially, he set out alone on a donkey to perform the pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina. However, he later joined a caravan for his safety—young men traveling alone on horseback or donkey often became targets for robbers and gangs.

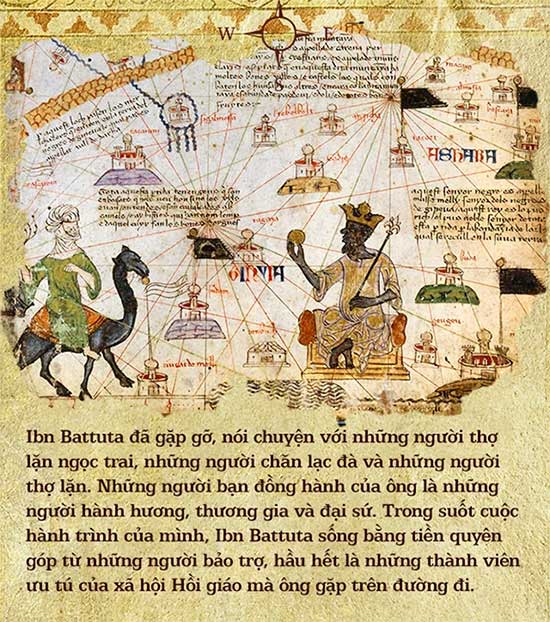

But traveling with this caravan was not easy; Battuta frequently fell ill in the early days, reaching a peak where he suffered from a high fever and had to tie himself to the saddle to avoid falling off and being left behind.

As time went on, he gradually adapted to the journey and even managed to marry a young woman along the way—she was just the first of many women Ibn Battuta would marry throughout his adventures.

The first leg of the journey took Battuta to Egypt along the northern coast of Africa. There, he toured Cairo, Alexandria, and historical sites, finding himself captivated by the people and Islamic culture. From there, Ibn Battuta continued to Mecca, his intended destination, where he completed his Hajj pilgrimage.

After completing the pilgrimage, most people would return home. However, Battuta felt compelled to continue exploring and learning new things, leading him to depart for Iraq, Western Persia, and then Yemen and the Swahili coast of East Africa.

By 1332, he reached Syria and Anatolia, crossing the Black Sea and entering the territory of the Golden Horde. Ibn Battuta visited the steppes along the Silk Road and reached the oasis of Khwarizm in western Central Asia. He then traversed Transoxania and Afghanistan, arriving in the Indus Valley in 1335 and moving deeper into India. Here, Battuta relied on his experience as a religious scholar to earn a living, serving as qadi in the court of Muhammad Tughluq, and even settled for a brief time to marry (once again) and have children.

However, his nomadic lifestyle came to an end in 1341 when Tughluq appointed him to lead a diplomatic delegation to the Yuan dynasty emperor in China. But the trip did not go as planned. After encountering pirates and being caught in storms that sank many ships off the coast of India, he decided against heading directly east; instead, he traveled around southern India, reaching Ceylon and the Maldives, where Battuta once again became qadi under the local Islamic government.

About a year later, he decided to continue his journey, passing through Sri Lanka to the shipping port of Quanzhou, China. He was astonished by the scale of Chinese cities, declaring that they were larger and more beautiful than any city he had ever seen.

The End of a Journey, the Beginning of a Legacy

The journey to the East marked the point at which Ibn Battuta decided to return home. The return journey took Ibn Battuta back to Sumatra, the Persian Gulf, Baghdad, Syria, Egypt, and Tunis. He arrived in Damascus in 1348 just as the plague struck and safely returned home to Tangier in 1349. Afterward, he took a short trip to Granada and the Sahara, as well as to the Kingdom of Mali in West Africa.

Upon returning home in 1354, he enlisted the help of a young literary scholar from Andalusia named Ibn Juzayy to compile his memoirs—they edited Rihla, which in Arabic means “the journey.”

After the publication of Rihla, the manuscript circulated throughout various Islamic countries, but it was not heavily cited by Islamic scholars. However, it caught the attention of Western explorers in the 18th and 19th centuries, Ulrich Jasper Seetzen (1767–1811) and Johan Ludwig Burckhardt (1784–1817). They purchased copies of Rihla during their travels across the Mideast. The first English translation of those copies was published in 1829 by Samuel Lee. Today, Rihla is regarded as one of the most comprehensive texts on life in the 14th century and one of the most fascinating accounts of life in various empires.