You may have thought, like many others, that letting dogs relieve themselves on the ground is fine since their waste acts as fertilizer, helping plants grow. However, a new study by Belgian scientists may make you rethink this perspective.

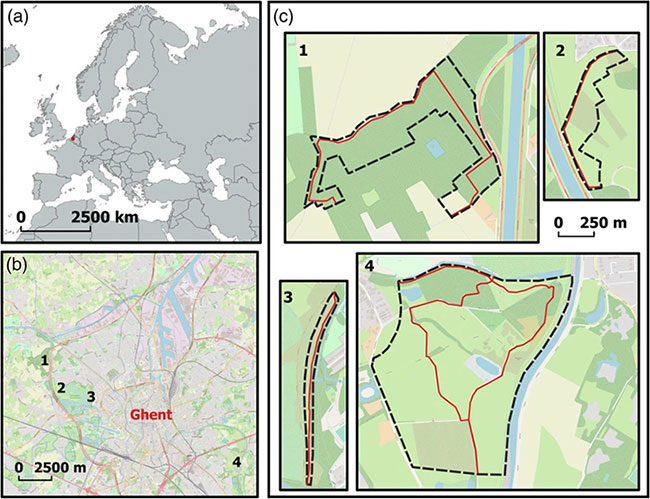

After monitoring a nature reserve on the outskirts of Ghent for over a year, they discovered that dog feces and urine have become significant pollutants, adversely affecting the plant ecosystem and wildlife populations in the area.

Each year, every hectare of land along the four roads running through the reserve in Ghent receives up to 11.5 kg of nitrogen and 4.8 kg of phosphorus. Nitrogen comes from both dog feces and urine, while phosphorus is primarily found in feces.

At such high concentrations, the researchers believe these two chemicals, typically found in fertilizers, can contaminate the soil, significantly impacting biodiversity and ecosystem functioning.

Dog feces and urine have become significant pollutants affecting the plant ecosystem.

The new study, published in the journal Ecological Solutions and Evidence, is the work of biologists from Ghent University. Over a year and a half, they recorded a total of 1,629 dog-walking visitors to the nature reserve.

The scientists found that while the reserve has rules requiring dogs to be leashed, about one-third of visitors in Belgium do not comply with this regulation. As a result, dogs can run freely and urinate and defecate indiscriminately.

“We observed that in areas surrounding the pathways, the levels of phosphorus and nitrogen entering the soil exceeded legal limits for fertilizers used in agriculture,” said Pieter De Frenne, the study’s author.

His calculations indicate that all the dogs visiting the nature reserve in Ghent each year produce 175 kg of nitrogen and 73 kg of phosphorus. If all pet owners complied with the leash regulations and cleaned up after their dogs, the model suggests that nitrogen pollution could be reduced by 56% and phosphorus pollution by 97% along the reserve’s pathways.

Many people often walk their dogs off-leash in the reserve, despite regulations requiring them to be leashed.

The figures from this study emphasize the importance of leashing dogs and cleaning up their waste in green spaces. Scientists indicate that letting dogs roam freely and allowing them to urinate and defecate indiscriminately can impact ecosystems in ways that pet owners may not realize.

“The nutrient input into the soil from dog waste is so high that even we were surprised,” Frenne noted. In Europe, emissions from fossil fuels and agriculture can contribute between 5-25 kg of nitrogen per hectare of land. Dog feces and urine can add a similar amount.

The dog population in Europe is currently estimated at 87 million. Each day, they must urinate and defecate. The waste passing through their bladders and intestines is full of nitrogen and phosphorus. Unfortunately, dog feces and urine are not widely recognized as a significant source of pollution.

So, what are the consequences?

The nature reserve in Ghent is threatened by dog feces and urine.

Scientists warn that if the soil becomes saturated with macronutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus, the local ecosystem could be altered. High levels of nitrogen and phosphorus allow certain plant species to thrive while restricting a group of other plant species, including those on conservation lists due to being threatened.

The dominance of one group of plants can lead to competition for nutrients and light with other plant groups. Ultimately, nitrogen and phosphorus-loving species may overpower the others.

Plants are crucial inputs in the food chain. The abundance of one plant species, coupled with the decline of others, creates fluctuations in herbivore populations. Herbivore populations continue to affect predator species that hunt them.

“Clearly, the level of pollution from dogs that we estimate here can have negative impacts on biodiversity and ecosystems,” the authors of the new study stated.

A sign requiring pet owners to clean up after their pets in the reserve.

Thus, they propose that regulatory authorities should implement a ban on dogs or require dog owners to clean up their waste in green spaces such as national parks, reserves, and even beaches.

Conversely, to reduce the pressure of bringing dogs to reserves, the study suggests that parks should relax their policies, allowing dogs to run and roam freely in areas where their waste is more manageable.

However, even if a ban is implemented, the model indicates it will still take years to restore the ecosystem in affected areas if it has been heavily contaminated with nitrogen and phosphorus, accumulating over many years.

In summary, this new study serves as a warning that we are underestimating dog waste as a significant source of soil pollution. If this issue is not addressed at its root, our nature restoration goals may be impacted in subtle ways that we are unaware of.